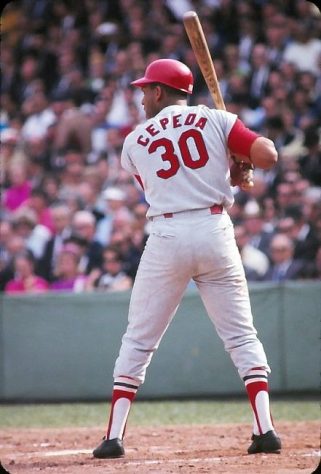

The late Pete Rose, shown at a signing table at 2023’s GalaxyCon in Columbus, Ohio.

Those to whom Donald Trump points the way to wisdom by standing athwart it have further evidence to present. The president who thinks (yes, those four words isolated by themselves would flunk a polygraph) he knows all says he will pardon the late Pete Rose. On which grounds, you ask?

Let the man speak a moment:

Major League Baseball didn’t have the courage or decency to put the late, great, Pete Rose, also known as “Charlie Hustle,” into the Baseball Hall of fame. Now he is dead, will never experience the thrill of being selected, even though he was a FAR BETTER PLAYER than most of those who made it, and can only be named posthumously. WHAT A SHAME! Anyway, over the next few weeks I will be signing a complete PARDON of Pete Rose, who shouldn’t have been gambling on baseball, but only bet on HIS TEAM WINNING. He never betted against himself, or the other team. He had the most hits, by far, in baseball history, and won more games than anyone in sports history. Baseball, which is dying all over the place, should get off its fat, lazy ass, and elect Pete Rose, even though far too late, into the Baseball Hall of Fame!

Is there anyone within the oatmeal-for-brains arterials of the second Trump Administration with the will and the backbone to counsel him that he’s talking through his chapeau? Seeing none thus far, I volunteer, though I’m not of the Trump or any other government administration.

To begin, unless Trump speaks of Rose’s conviction and sentence served for tax evasion having to do with his income from memorabilia shows and sales, his power of the pardon doesn’t reach major league or other professional baseball.

Herewith a memory refreshment for the president who once opined—erroneously, unless Congress is still foolish enough to transfer its responsibilities to the White House—that Article II of the Constitution, which codifies the president’s job, enabled him to do as he damn well pleased: From Section 2, Article II: The President shall . . . have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.

Rose’s violations of Rule 21 weren’t legal offences against the United States. Moral and cultural violations are other stories, of course. (And how, when it came to Rose, alas.) Sorry, Mr. President. (That’s Mr. President, not Your Majesty, Your [In]excellency, or Your Lordship.) That only begins to convict you of erroneous assault with a dead weapon.

Consider: Rule 21’s prohibition of MLB personnel betting on MLB games does. not. distinguish. between betting on one’s team to win and betting on one’s team to lose. The notebooks whose revelations affirmed the depth of Rose’s betting on baseball that began while he was a player/manager affirmed concurrently that there were days aplenty when Rose’s baseball bets didn’t include bets on his Reds.

Read carefully, please: In the world of street/underground/extralegal gambling, a player or other team personnel known to bet on baseball but not laying a bet down on his team on a particular game sends signals to other street/underground/ extralegal gamblers not to bet or take betting action on that team. That’s as de facto betting against your team as you can get.

Now, about that business of, “He had the most hits, by far, in baseball history, and won more games than anyone in sports history.” Rule 21 doesn’t make exceptions for players who achieve x number of milestones or records. Especially not the clause that meant Rose’s permanent (not lifetime) banishment: Any player, umpire, or Club or League official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform, shall be declared permanently ineligible.

Did you see any exception for actual or alleged Hit Kings?

If you count Nippon Professional Baseball as major league level, and its quality of play says you should, Rose’s 4,256 hits don’t make him the Hit King—but it does crown as such freshly-minted Hall of Famer Ichiro Suzuki with his 4,367, between nine seasons with the Orix Blue Wave (Japan Pacific League) and nineteen seasons with the Mariners, the Yankees, and the Marlins.

Did you see any exception for those who “won” more games than anyone in sports history?

Modesty wasn’t exactly among Rose’s virtues, but he liked only to brag that he had played in more winning major league baseball games than anyone who ever suited up. Played in. Even Rose never once said or suggested that he won those games all by his lonesome, with no help from the pitchers and the fielders who kept the other guys from putting runs on the scoreboard, or with no help from the other guys in the lineup who reached base and came home.

Baseball is “not in the pardon business,” said Rose’s original investigator John Dowd, in a statement to ESPN, “nor does it control admission to the [Hall of Fame].” Baseball’s commissioner could have reinstated Rose any old time he chose. The Hall of Fame, which is not governed by MLB though the commissioner sits on its board, enacts its own rules, including the rule barring those on the permanently-ineligible list from appearing on any Hall ballot.

Rose tried and failed to get two commissioners to end his banishment. The trail of years during which he lied, lied again, and came clean only to a certain extent. And he did the last only when it meant he could peddle a book. “[W]hat had once been a sensation,” his last and best biographer Keith O’Brien wrote (in Charlie Hustle: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball), “quickly became yet another public relations crisis for Pete Rose.”

Somehow, his book managed to upset almost everyone . . . He refused to admit that he bet on baseball in 1986 while he was still a player, despite evidence showing otherwise. At times, he painted himself as the victim. Even the book title–My Prison Without Bars–sounded whiny, as if he hadn’t helped build the prison walls with his own choices . . . He picked fights over little pieces of evidence instead of taking full responsibility for his mistakes. He didn’t sound very sorry, critics said, and reinstatement eluded him every time he asked for it: in 2004, in 2015 and 2020, and in 2022. Nothing changed. If anything, his situation only grew worse.

Not even Rose’s jocularity when signing autographs or bantering with fans who met him in the years since his banishment could rescue him. Perhaps that was because, in part, it was tough to tell whether he was just kidding or sending none-too-subtle zingers at the critics he really believed done him wrong. Sorry I bet on baseball. No Justin Bieber, I’m sorry. Build the wall for Pete’s sake. Sorry I broke up the Beatles. I’m sorry I shot J.F.K. About the only thing missing was, I’m sorry I built the Pontiac Aztek.

Only one man was responsible for Rose’s exile to baseball’s Phantom Zone. It wasn’t his original investigators, or the commissioner who banished him under the rules, or the commissioners who denied his reinstatement petitions in the years that followed until his death of hypertensive atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease last fall.

“All his adult life,” wrote another freshly-minted Hall of Famer (writer’s wing division), Thomas Boswell, after Rose was first banished in August 1989, “he has thought, and been encouraged to think, that he was outside the normal rules of human behaviour and above punishment. In his private life, in his friendships, in his habits, he went to the edge, then stepped over, trusting his luck because—well, because he was the Great Pete Rose.”

Funny, but with just a name change at the end, and regardless of party affiliation or ideological core, you could say the same thing about more than one president of the United States. Including and especially the once and current incumbent.