The way some people talk, you’d think this was baseball’s version of the ancient Roman Colosseum, the Dodgers are the Evil Empire, Dodger owner Mark Walter is Emperor Nero, and the Dodgers plan to throw Christians to the lions.

The question used to be, “How can you tell whether a lawyer or a politician (do we repeat ourselves?) lies?” The answer, of course, was, “One’s mouth is moving.”

Asking if you can tell whether most baseball owners lie just by moving mouths has not been unreasonable for an unreasonable length of time. Asking likewise of baseball’s commissioner is even less unreasonable anymore.

Rob Manfred leads the charge toward imposing a players’ salary cap at long enough last. For every time he mentions a players’ salary floor, a minimum payroll per team, the salary cap comes out of his mouth about twenty times, roughly counting.

It’s as though the idea of the owners not named the Dodgers investing conscientiously in putting the most competitive possible teams onto the field in honest efforts to win is an affront to whatever it might be that Manfred holds dear. But it’s a waste of breath to remind anyone anymore than money alone doesn’t guarantee championships.

The 2025 Dodgers didn’t win one of baseball’s most thrilling World Series of all time because they put a $321.3 million player payroll forward on Opening Day. They won it because their postseason roster played championship baseball right down to the last minute.

Their opponents from Toronto didn’t win the American League pennant because they put forth an Opening Day player payroll about $100 million lower. They won it, and damn near won the World Series in the bargain, because their postseason roster played championship baseball right down to the next-to-last minute.

Nine 2025 teams fielded player payrolls of $200+ million. One sub-$200 million payroll went to last year’s postseason (the Cubs, at $196.3 million) and lost in the first round. The number three payroll (the Yankees, $293.5 million) lasted into the second round. Five other sub-$200 million payrolls (the Reds, the Guardians, the Tigers, the Brewers, the Mariners) entered the postseason and two (the Brewers, the Mariners) got as far as each League Championship Series.

The number four 2025 player payroll (the Phillies, $284.2 million) got knocked out by the Dodgers in a division series. Three $200+ million 2025 player payrolls (the Braves, the Astros, the Rangers) didn’t get to the postseason at all.

And the number one 2025 player payroll didn’t get to the postseason either. The Mets were too busy going from as high as 5.5 games above the National League East pack to 13 games out of first place and not even eligible for a wild card—because the Reds, with a sub-$130 million 2025 player payroll, won their season series against the Mets and thus won a wild card tiebreaker.

“Here’s a question: Who, exactly, is the salary cap for?” writes USA Today‘s Gabe Laques. He answers with questions baseball’s would-be salary cappers would rather not confront until the next-to-last minute or a lockout, whichever comes first:

Is it so the upper-middle class teams—your Red Sox, Phillies, Giants, Blue Jays, Yankees, Cubs—can stay within shouting distance of the Big Two?

To provide a puncher’s chance for the most bedraggled among us—your Pirates and Marlins, Royals and Reds?

This is where it gets challenging to determine if the cap would actually help—or if some of those franchises would simply continue their same aversion to serious competition, pocket their shared revenues and lock in even greater profits for every other franchise.

Those last nine words strike to what so often seems the nearest and the dearest to Manfred’s heart, even ahead of his inveterate tinkering: the common good of the game as making money for the owners.

Never mind the Dodgers being pushed out of two straight postseasons in division series losses before they won their two straight World Series, as The Athletic‘s Tyler Kepner notices. (Or, that they’d won exactly one World Series between the end of the Reagan Administration and the beginning of the COVID-19 pan-damn-ic.) Never mind, either, that they got the push-outs from the Padres and the Diamondbacks.

“It is easy now,” writes Kepner, “to forget how random short series really are.”

It’s been a terribly kept secret that Manfred has longed to see baseball achieve some sort of equivalence to the big bad NFL. “Setting aside for a moment the virulent anti-labor landscape of the NFL,” Lacques writes, “it is clear that its salary cap does not solve many of the problems some baseball fans claim is now endemic in their un-capped sport.”

He reminds baseball’s pro-cap Chicken Littles that the past eighteen Super Bowls have featured a whopping . . . eight NFL franchises. (That’s not going to change this year, folks. It’s going to be the New England Patriots and the Seattle Seahawks.)

It gets better. The AFC Championship Game has featured either or both of the Patriots and the Kansas City Chiefs over the past fifteen seasons, a span during which only twelve teams reached the Super Bowl. How many baseball teams have reached the World Series in that same fifteen-year span, starting with 2011, Lacques asks? Answer: Eighteen.

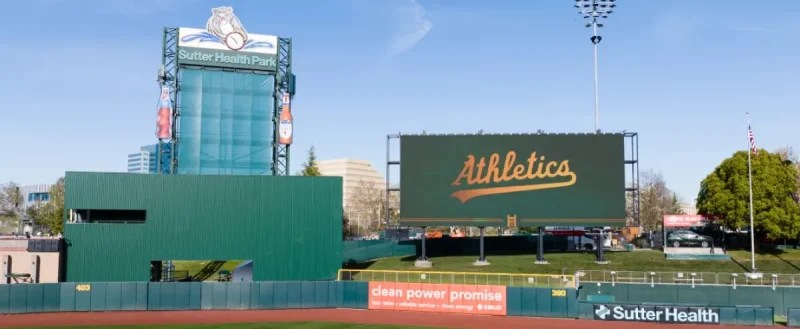

Eighteen, which means it’s easier to reel off the ones who didn’t make the Fall Classic: Baltimore, Minnesota, the Chicago White Sox, Seattle, Oakland/Yolo Countys, the Los Angeles Angels, Miami, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, San Diego and Colorado.

The Padres, Orioles, Brewers and Mariners all reached a league championship series in that time. Do the remaining franchises strike you as particularly well-run? Do they have distinguished ownership groups with clear vision and a penchant for innovation? Consistently operate at a high level?

Try one example: The Angels aren’t exactly dirt poor. They were 2025’s number thirteen player payroll. ($190.5 if you’re scoring at home. Not Dodger dollars but not exactly Pirates penury, either.) Anyone accusing the Angels of having a distinguished owner with a clear vision and a penchant for innovation would lose in a court trial.

The Arte Moreno Angels have made tunnel vision a way of life. They’ve wasted the Hall of Fame-worthy prime life of the greatest position player the franchise has ever known. They couldn’t even show the brains to trade the game’s unicorn two-way player for geniune value before his contract expired.

They let Shohei Ohtani escape to free agency with an expected income equal to the economy of a tiny island country . . . before the Dodgers convinced him they believed in winning more than they believed in making generational talents surrealistically wealthy.

It’s not the only such example in major league baseball. The Angels are merely the least obscure of such franchises whose ownerships are vision impaired and innovation challenged. The ownerships that think their problems are . . . all the Dodgers’s or the Mets’s fault. (Did you ever think you’d see the day when the Yankees were no longer baseball’s Evil Empire?)

“The players and owners should find creative ways to dull the Dodgers’ edge, so other teams can come closer to matching it,” Kepner writes. “But you cannot make the Dodgers dumber or less driven to win. And as long as they are smart, motivated and opportunistic, this era will belong to them.” The first two, especially.

“For now,” Lacques writes, “[the Dodgers and the Mets] are the game’s pariahs, their proverbial hands slapped for trying too hard. The industrywide price, in management’s eyes, should be a salary cap. A greater solution: A little more competence and a little more care from those who have displayed precious little of either.”

A little more competence. A little more care. What concepts.