Pete Rose’s longtime Reds manager was almost as incessantly quotable as Rose. “We try every way we can think of to kill this game,” Sparky Anderson once said, “but for some reason nothing nobody does never hurts it.” The Hall of Fame manager wasn’t necessarily talking about Rose. But he could have been.

Pete Rose’s longtime Reds manager was almost as incessantly quotable as Rose. “We try every way we can think of to kill this game,” Sparky Anderson once said, “but for some reason nothing nobody does never hurts it.” The Hall of Fame manager wasn’t necessarily talking about Rose. But he could have been.

When Rose became the first back-to-back National League batting champion in a Reds uniform, Ohio governor James Allen Rhodes declared Pete Rose Day in the state and Cincinnati elected to re-name his favourite childhood park, Bold Face Park, as Pete Rose Playground. Five hundred citizens signed a petition opposing the name change.

“They didn’t think Pete Rose was worthy of a local landmark,” writes Rose’s newest biographer, Boston Globe writer turned NPR contributor Keith O’Brien, “perhaps because there were growing questions and rumors about him—questions and rumors that even West Siders couldn’t ignore. One of the rumors circulating about Pete concerned gambling. He seemed to do a lot of it.”

Indeed. He was about to graduate from merely spending a lot of time at the race tracks to befriending and betting through bookies. Violating a lesser-known clause of baseball’s Rule 21 long enough before he began betting on the game itself. “I was raised, but I never grew up,” was one of Rose’s most widely-disseminated quotes. That was probably the root of the problems that finally steered him toward that which got him a permanent ban from baseball and a concurrent ban from appearing on a Hall of Fame ballot.

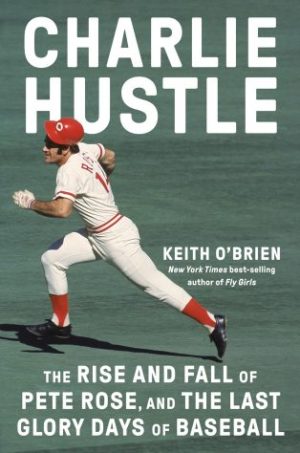

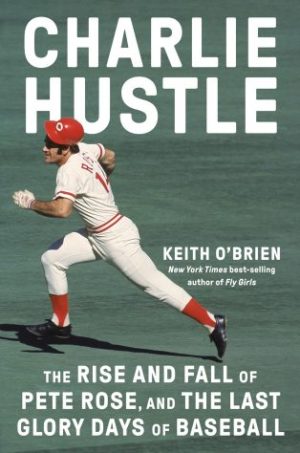

Maybe no book heretofore written about Rose goes quite as deep into his self-making and his self-unmaking as O’Brien’s Charlie Hustle: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball does now. But this fresh excursion into Rose’s life and legacy leaves little room to conclude other than what O’Brien himself writes almost at the outset:

He was Icarus in red stirrup socks and cleats. He was the American dream sliding headfirst into third. He was both a miracle and a disaster, and he still is today.

O’Brien didn’t build his work idly or incompletely. A Cincinnatian himself, he plunged as fully into Rose’s world as possible, from talking to former teammates, former baseball commissioners, former Rose investigators, family, friends, adversaries, to talking to Rose himself—twenty-seven hours worth with Rose, “before he stopped calling back, before he shut down.” The author also plowed through scores of federal court documents and even FBI files as well as ages of published articles as well as the Dowd report that first put paid to Rose’s baseball life.

Charlie Hustle is a long, page-turning, heartbreaking re-examination of the Rose who willed himself into becoming a baseball symbol and sank himself into becoming a baseball pariah. Maybe it’ll convince his most stubborn apologists that their hero was his own destroyer. Maybe it’ll convince his most stubborn critics that being right about him doesn’t equal being proud of that.

To those who loved him, and even to more than a few who thought he was excessive at minimum, Rose the player was like the junkyard dog deciding he’d hang with those Westminster dandies any old time he chose, no matter what he lacked. To the same people, Rose was just a particularly extreme manchild. One remembers Thomas Boswell quoting then-Orioles general manager Hank Peters not long after the end of Rose’s fabled 44-game hitting streak: “The Reds have covered up scrapes for Pete his whole career. He’s always been in some little jam . . . but people never seem to hold it against him.”

Maybe that perception took hold because nobody in the sports press then really wanted to risk losing one of the best and most available quotes in the game. Not to mention a star player whose generous side—welcoming rookies and newly-acquired veterans enthusiastically, helping them remake or remodel their approaches, joining them in business ventures, standing by them against bigots—was almost as talked up as his bull-headed playing style and his gift of gab.

Nobody then wanted to expose the Rose who ran around on his first wife, often flagrantly, with younger women, one a teenager Rose swore was sixteen (Ohio’s legal age of consent) but who later said she’d been fifteen at the start. Or, the Rose whose taste for sports betting began to look like more than just simple, occasional recreation. It took over a decade to follow before Rose’s rough-hewn mythology began to implode and the sports press that once adored him began to comprehend that this wasn’t just a more coarse boys-will-be-boys type.

Headlines in early 1979 about Rose being sued by the extramarital mother of a baby girl by him exposed him publicly as an adulterer and deadbeat (she sued after Rose stopped sending her payments for the baby) long before his exposure for not paying many of his gambling debts. So did first wife Karolyn divorcing him in 1980. (As earthy as her husband, Karolyn also confronted the mistress who’d become Rose’s second wife, whom she spotted driving her Porsche—and opened the door to punch her out.)

When did this scrappy, witty rogue, who could and did will himself into Everymanperson’s Hero, really begin crossing the line from mere recklessness to self-immolation? Some time in the early 1970s, as he began to graduate from mostly a Cincinnati star to a national baseball figure, Rose became friendly with Alphonse Esselman, a bookmaker freshly released from federal prison, now using a used car lot as a front, and first meeting Rose at the River Downs track.

Esselman’s initial appeal for Rose was an ability to speak of sports equal to Rose’s own, which must have been formidable enough. Rose also began betting on football and college basketball games through Esselman, “almost every night and certainly on Saturdays and Sundays in the fall, after baseball season was over,” O’Brien writes.

At home, especially on big football weekends, Pete disappeared into a room and watched games all day. Karolyn saw him when he emerged for snacks from time to time or for dinner, and throughout the day, she could hear him in there, shouting. “Plenty of time,” he’d say, figuring spreads and probabilities in his mind. But it was almost as if he were gone, lost inside a world of his own making, a world that could destroy him. By consorting with Al Esselman and placing bets with him, Pete was violating a rule of baseball known by every player.

Had it stayed purely with that, Rose at worst might have faced a discretionary punishment from baseball’s commissioner, not necessarily one that got him his permanent banishment. Maybe something similar to the one Happy Chandler inflicted upon Dodgers Leo Durocher in 1947 (a full season) for hanging with bookies. Maybe something similar to what Bowie Kuhn inflicted upon Tigers pitcher Denny McLain (indefinite but reduced to ninety days) for becoming one, involving non-baseball games.

“By 1984, Pete had graduated from placing bets with friendly West Side bookies like Al Esselman to hanging around shady, small-time mobsters and established East Coast criminals,” O’Brien writes, referencing the time before the Reds dealt to bring Rose back from the Montreal Expos, where he played after his term with the Phillies.

Pete had reportedly started placing bets with a syndicate run out of Dayton by Dick Skinner, an old-school bookie and convicted felon known to authorities as “the Skin Man.” Skinner was believed to be the largest bookmaker in southeast Ohio, and to Skinner’s dismay Pete fell thousands of dollars behind on his payments. Skinner was soon

complaining about Pete all over Dayton and Cincinnati. Then, in early 1984, Pete made a new gambling connection: Joe Cambra, a man on the fringes of the Rhode Island mob with dark eyes, dark hair, a home in southern Massachusetts just across the Rhode Island

border, and a winter retreat in West Palm Beach not far from the Expos’ spring training facility.

. . . Unaware that anyone was watching, Pete paid off his debts to Cambra on July 5, 1984, with two checks—one from his personal account in Ohio for just over $10,000 and a second from the Royal Bank of Canada for $9,000. Pete then had a great week at the plate.

“He was Icarus in red stirrup socks and cleats.”—Keith O’Brien.

That August, prodigal Reds general manager Bob Howsam decided to bring Rose home to Cincinnati as their player-manager, “despite all the warning signs and things he knew to be true.” One of Rose’s first doings after returning to Cincinnati was joining a Gold’s Gym there, one known as a clearinghouse of sorts for illegal performance substances, and where Rose and his youthful baseball protegé Tommy Gioisia met one Paul Janszen, who’d join with Gioisia in placing Rose’s bets with bookies. Including one Ron Peters.

Rose’s eventual success in breaking Ty Cobb’s lifetime hits record was the opposite of his success as a gambler. He was into enough bookies for enough money by March 1986 that, according to the Michael Bertolini notebooks revealed in full in 2015, O’Brien writes: “Pete was gambling on baseball by at least April and May 1986—with a handful of bets on the Yankees, Mets, Phillies, Braves, and his own team, the Reds. To crawl out of the hole he had dug for himself that March, Pete had apparently started wagering on the thing he knew best: baseball.”

In time, and with the feds investigating Rose’s gambling associates and connections, Sports Illustrated went digging and intended to run with what they discovered about Rose’s betting. Not so fast, determined baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth, in February 1989, calling Rose to New York to meet with him and National League president A. Bartlett Giamatti, we can’t afford to wait for that magazine to run with it.

O’Brien reminds us Ueberroth didn’t want to just hand this off to Giamatti and hoped against hope that Rose would come clean, admit he’d made a phenomenal mistake, and save himself. “But Pete couldn’t do it. He wouldn’t do it.”

The same qualities that made him a successful baseball player—and one of the greatest hitters of all time—ensured his failure now. Pete wasn’t going to let Paul Janszen win, if that’s what this was about. He wasn’t going to admit to anything in that room on Park Avenue filled with polished men wearing the right kinds of suits. He was going to fight his fight . . . He was going to listen to his late father. “Hustle, Pete. . . . Keep up the hustle.” He was going to foul off the fastball on the outside corner to see another pitch. He was going to bunt the ball down the line to win the batting title, and he was going to take out the catcher at home plate in a meaningless game, breaking his shoulder at the joint.

Pete Rose was going to lie.

Sure, Pete admitted in the room in New York, he was a gambler and he bet on lots of things: the horses, the dogs, even football games. But no, he said that day. He did not bet on baseball.

“I’m not that stupid,” [Giamatti’s aide Fay] Vincent recalled him saying.

Exit Ueberroth, enter Giamatti as his successor, enter John Dowd leading baseball’s official investigation, and exit Rose to baseball’s Phantom Zone, soon enough. Enter, too, the Hall of Fame, entirely on its own (one more time: it’s not governed by MLB itself), electing quite reasonably to bar those considered persona non grata by baseball from appearing on any Hall of Fame ballot.

Let’s reiterate yet again that baseball’s Rule 21(d)’s mandate of permanent banishment for betting on one’s own team (O’Brien reminds us that days Rose didn’t bet on the Reds one or another way were still signals to other gamblers regarding the Reds) doesn’t make exemptions a) for a player who broke a once-thought-impossible-to-break record; b) for a player with Hall of Fame credentials; or, c) for a player-manager who claimed only to have bet on his team to win.

Let’s reiterate, further, that the firestorm over Shohei Ohtani’s now-former interpreter Ippei Mizuhara and the latter’s gambling through an Orange County bookie (sports betting remains illegal in California) doesn’t take Rose off the hook. Nor do baseball’s promotional deals with legal sports betting Websites and companies.

Fans can bet on baseball whenever they like. Players, managers, coaches, trainers, clubhouse workers, front office people, can bet on any sports they like—except baseball. They can play fantasy football, bet on the Final Four, bet the horses or NASCAR, round up high-stakes poker or pinochle games. Anything that catches their competitive eyes. Except baseball.

If Rose as a player-manager and then manager alone had never crossed the line into betting on baseball itself, his story would have had a very different turn in 1989. He might still have graduated from a mere visceral rogue to a scoundrel with an addiction, but he might have been elected to the Hall of Fame regardless.

Rose’s Hall of Fame teammate Johnny Bench was once asked when he thought Rose—who triumphed under baseball’s most heated lights, and fell under the detonations of his own explosives—should be brought back in from baseball’s cold. Bench’s answer: “As soon as he’s innocent.” Charlie Hustle says, in essence, that’s not happening.

Pete Rose’s longtime Reds manager was almost as incessantly quotable as Rose. “We try every way we can think of to kill this game,” Sparky Anderson once said, “but for some reason nothing nobody does never hurts it.” The Hall of Fame manager wasn’t necessarily talking about Rose. But he could have been.

Pete Rose’s longtime Reds manager was almost as incessantly quotable as Rose. “We try every way we can think of to kill this game,” Sparky Anderson once said, “but for some reason nothing nobody does never hurts it.” The Hall of Fame manager wasn’t necessarily talking about Rose. But he could have been.