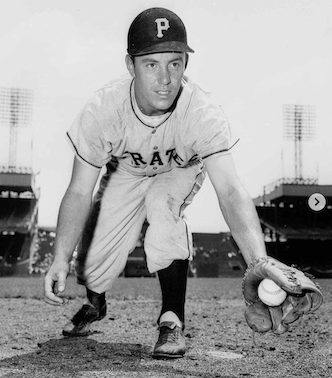

Striking a pose in the Polo Grounds during his earliest Pirates seasons, Bill Mazeroski shows what really got him into the Hall of Fame at long enough last.

Let’s get it out of the way right away. “I was gonna hit one out,” said Dick Stuart, the on-deck batter. “Could I help if it Mazeroski decided to get cute?”

There. The best gag to follow after Bill Mazeroski hit the 1960 World Series-winning home run is resurrected just long enough and, now, cast aside. Because anyone who thinks the greatest defensive second baseman ever got into the Hall of Fame because of that home run alone should be dismissed unceremoniously.

Mazeroski died Friday at 89. The Game Seven-ending homer he hit to hand his Pirates a World Series win despite being outscored 55-27 will live in baseball lore as long as baseball itself lives, of course. Neither Dr. Strangeglove nor any other Pirate could help it if Maz decided to get cute.

It’s also one of the absolute classic instances of a player doing something so far above his own head the most powerful telescope available won’t locate it. If the only way you judge a ballplayer is at the plate, Mazeroski is too much of a piece with other mere mortals delivering transdimensionally immortal moments:

* Bumpus Jones pitched only one full major league season, 1892. His 10.19 ERA may explain a lot about why. The year before, he got to pitch one game . . . and became the first major league pitcher ever to pitch a no-hitter in his first-ever major league start. Go figure.

* Bobby Lowe is sixteen places outside the top one hundred second basemen of all time, but in 1894 he was the first major league player ever to hit four home runs in a single game.

* Howard Ehmke snuck one notch inside the top two hundred starting pitchers the game’s ever seen. With his career about to end, he was the surprise starter for Game One of the 1929 World Series. And he surprised everyone, perhaps even himself, by setting the single-game Series strikeout record (13) and doing it in large enough part at the expense of three Hall of Famers whom he struck out twice each. (Kiki Cuyler, Rogers Hornsby, and Hack Wilson.) His record was broken eventually by Carl Erskine, who was broken by Sandy Koufax, who was broken by Bob Gibson

* Don Larsen was the number 231 starting pitcher in the major league game’s history . . . but in 1956 he pitched the first and so far only perfect game in World Series history.

* Bill Mazeroski, a lifetime .260 hitter who hit slightly below average for second basemen, and had a lifetime .299 on-base percentage, hit the first and so far only World Series-winning Game Seven walkoff home run.

That quintet yielded forth one Hall of Famer. And he didn’t get there because he was the second coming of fellow Hall of Fame second baseman Rogers Hornsby, his diametric opposite in more ways than one. (Never mind the statue outside PNC Park’s right field gates, showing Mazeroski rounding second and waving his outstretched batting helmet after hitting that home run.)

Hornsby hit about ten tons in his prime and showed the pre-integration National League what it was like (and how bad it wasn’t) to have Babe Ruth or close enough to him in your league. But he was league-average at best at second base. And, he was described most politely as the cantankerous personality type.

Mazeroski could barely hit ten ounces. Some people might still be trying to figure out just how he averaged drawing eight intentional walks a season or hitting 13.8 home runs a season. (The National League’s pitchers weren’t that generous.) But slip a glove onto his left hand and he became second base’s answer to Brooks Robinson. (Or was Brooks Robinson third base’s answer to Bill Mazeroski?)

Maz’s 148 total defensive zone runs above his league average remain the best among second baseman in major league history. (His nearest trailer: Frank White, the longtime Royals second baseman, with 126.) When he retired after the 1972 season (and a second World Series ring, with the 1971 Pirates), he was believed to own the best defensive statistics of any player at any position, ever, pending the final outcome of Robinson’s career. (Total Baseball, the pre-Retrosheet baseball co-Bible, ranked the eight-time Gold Glove-winning Mazeroski the best fielder at any position, ever.)

The Hall of Fame voters weren’t in a big hurry to elect him.

“What he has to sell,” wrote Bill James in The Politics of Glory, “is lots and lots of defense, and the Hall of Fame isn’t buying. Trying to sell defense to the Hall of Fame is like trying to sell diplomacy to a terrorist. They may listen politely, but what they’re really looking for is big guns.” (Which reminds me: Hands up to everyone who barely remembers Mazeroski also hit a two-run homer in Game One of that 1960 Series to put that game out of Yankee reach, too.)

Come 2001, in The New Historical Baseball Abstract, James wrote that his own Win Shares system credited Mazeroski—whose other nickname was No-Touch, in honour of the speed at which he released a ball to start turning a double play (it was the speed of light, we think we remember)—with 113 such shares for his second base defense, “the highest total of all time.”

Some way, somehow, one of the last of the pre-Era Committee-partioned Veterans Committee finally caught on to the idea that run prevention was just as important to winning ball games as run production. Maybe slightly superior. “[T]he Cubs have had two problems,” wrote George F. Will during the peak (?) of their 108-year rebuild between 1908 and 2016. “They put too few runs on the scoreboard and the other guys put too many.” Good pitching isn’t the only thing that beats good hitting.

James once related that Dave Cash, who succeeded Mazeroski at second base, had no problem at all waiting around for Mazeroski’s age to overthrow him at long enough last. “Actually,” he quoted Cash as saying, “I learned a lot from Mazeroski.”

He’s a real man, and one of the things he taught me was to keep things in perspective. Maz didn’t make many errors, and he hardly ever made any bad plays, but when he did, he didn’t let it bother him. He was always the same, whether things were going good, bad, or indifferently.

A man that sanguine, whether playing second base or teaching it (as he did for numerous years to follow as a Pirates spring training instructor) is going to make short and sweet work of his Hall of Fame induction speech. That’s exactly what Mazeroski did when his (long overdue) time came, shamelessly letting emotion come forth before he finished:

I think defense belongs in the Hall of Fame. Defense deserves as much credit as pitching and I’m proud to be going in as a defensive player. I want to thank the Veterans Committee for getting me here. I thought when the Pirates retired my number [9] that would be the greatest thing ever to happen to me. I don’t think I’m gonna make it, I want to thank everyone who made the trip up here to listen to all this crap …Thank you to everybody.

As had been so while turning 1,706 double plays (it’s still a major league record), Mazeroski’s timing couldn’t have been more perfect. Just a year after he pronounced defense as Hall of Fame important in its own right, the platinum standard for shortstops, Ozzie Smith, was inducted.

We can allow thoughts of Maz and The Wiz in the same middle infield in our imaginations alone. But boy, what those imaginations would show us, to the chagrin of a few too many hitters learning the hard way how easy it isn’t to sneak something past them.

Worry not that Mazeroski reunited with his beloved wife in the Elysian Fields will drive her mad all over again. Milene Nicholson met him when she worked in the Pirates front office and married him in 1958. They were a couple until she preceded him to the Fields two years ago. Rest assured she’s kept the gloves ready for him near second base.