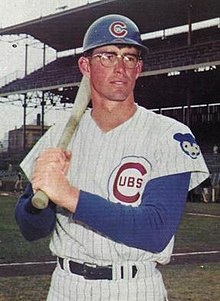

Don Young—two misplayed balls on 8 July 1969 triggered the postgame tirades that may have begun wrecking the 1969 Cubs.

While reading Wayne Coffey’s They Said It Couldn’t Be Done, the best book you’ll ever read about the 1969 Mets, I bumped into a jarring quote from 1969 Cubs relief ace Phil (The Vulture) Regan. It may—underline that—hold the opening key to how those Cubs, who looked at first like a National League East runaway, ended up collapsing as the Miracle Mets re-heated in earnest to reach the Promised Land.

On 8 July the Cubs tangled with the Mets in Shea Stadium to open a series and lost a game they led until the ninth inning. How the game was lost, and what two key Cubs said after the game, may have opened disaster’s door. It helped ruin the baseball life of the Cubs’ center fielder on the day, a rookie named Don Young who had an early reputation for being a promising defender with a fine arm. And it may have helped cost the Cubs the postseason.

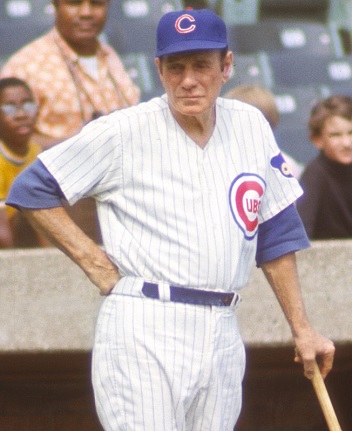

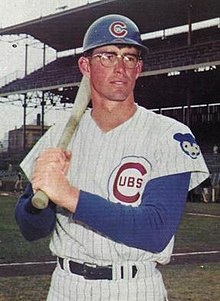

Young committed two misplays in the bottom of the ninth. Cubs manager Leo Durocher and Hall of Fame third baseman Ron Santo tore into Young in the press after the game. Young himself said, simply, “I lost the game for us. That’s all.” The Vulture was appalled—especially at Santo.

“Don Young was never the same after that,” said Regan, in remarks Coffey reprinted in full in his book. “He showered and left the ballpark as soon as he could get out of there. To this day, you never hear from him. Santo was the captain and a veteran. He apologised later, but it was done. You can’t do that. That hurt us.”

Hall of Famer Ferguson Jenkins got the start against the Mets’ redoubtable lefthander Jerry Koosman. They both went the distance until Koosman was lifted for a pinch hitter to open the bottom of the ninth with the Cubs ahead, 3-1. Jenkins and Koosman first swapped home runs, Ed Kranepool hitting one out in the bottom of the fifth and Hall of Famer Ernie Banks hitting out out in the top of the sixth. But Glenn Beckert drove a run home with a seventh-inning single and former Met Jim Hickman hit a two-out shot in the top of the eighth.

Mets second baseman Ken Boswell, who hadn’t started that day against Jenkins, now pinch hit for Koosman at a point where Jenkins had erased nine consecutive Mets. Boswell skied one to short center field. Young misread the ball at first but rehorsed in a split second and sprinted in, diving and missing as the ball landed in front of him and just away from onrushing Cub middle infielders Beckert and Don Kessinger.

Despite running full tilt on contact, Boswell was surprised to find himself on second with a double. Tommie Agee batted next and fouled out near first base, bringing up another pinch-hitter, Donn Clendenon. The veteran whom the Mets picked up in a deal with the infant Montreal Expos almost a full month earlier drilled one toward the left center field fence. Young turned, gunned it to the warning track, nailed the ball with a staggering on-the-run backhanded snap of his glove . . . and the ball dropped right before Young’s momentum crashed him into the fence with a thud. Leaving the Mets with second and third and one out.

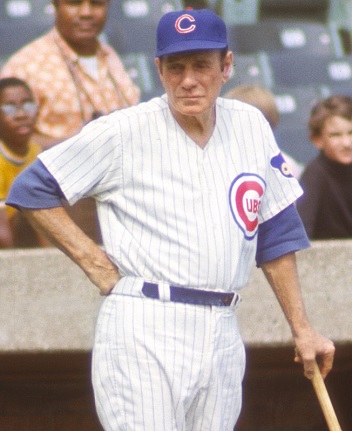

Leo Durocher—disgrace.

Branch Rickey once said Durocher’s genius included his ability to make a bad situation worse immediately. “Two little fly balls,” Durocher fumed after the game. “He just stands there watching one and he gives up on the other. It’s a disgrace. My three-year-old could have caught those balls.”

Durocher’s on-the-record tirade poured out with the hapless Young within clean earshot. The humiliated 23-year-old outfielder finished dressing and high-tailed it out of the clubhouse and the ballpark at once. Santo mistook that for apathy and, when Jerome Holtzman of the Chicago Sun-Times asked whether Santo heard Durocher’s tirade, the third baseman ripped Young a few new ones. On the record.

“He was just thinking about himself, not the team,” Santo steamed about Young. “He had a bad day at bat, so he’s got his head down. He’s worrying about his batting average and not the team. All right, he can keep his head down and he can keep right on going out of sight for all I care. We don’t need that kind of thing.”

Who were those two fools, and which game were they watching? Especially Santo, who’d previously been a mentor to Young, teaching him about the league’s pitchers and assorted outfield differences? It was one thing for the manager to rip a player in the press; however unwise it is, you get the manager doing it. It was something else for a teammate to do it, as Regan understood only too well.

Young did have a bad turn at the plate, going 0-for-4 with a pair of strikeouts in the game. According to David Claerbaut’s Durocher’s Cubs: The Greatest Team That Didn’t Win, Hickman told Santo to settle the rookie down after he’d slammed his bat and helmet after one of those plate appearances, but Santo grabbed Young and ordered him to do his job. So much for settling the rook down.

But Young still had time enough to shake that off, since his last plate appearance was his second strikeout, ending a 1-2-3 top of the eighth. He misread Boswell’s shuttlecock at first in a combination of the afternoon haze and the bright shirts on fans sitting behind the plate—for maybe a second, taking maybe a step and a half back before getting the right read at once and scampering in to try for the ball.

If that’s just standing there watching one, I’m Ray Charles.

But what happened to Young on the Clendenon drive could have happened to any center fielder including Willie Mays. He ran full speed to catch up to the ball and made a backhanded grab on the middle of the warning track. It might have gotten play of the game honours in a heartbeat if, while still on the full run, the ball didn’t fall out of his glove a split second before he crashed the fence like a battering ram.

Just in case Durocher and Santo suffered a deeper brain fart than their postgame comments already indicated, the Mets hadn’t scored yet, and the Cubs—who came into the series with a five-game lead over the upstart Mets—had two outs to go to finish them off on the day, with their best pitcher still working well enough.

The Mets’ hottest bat, left fielder Cleon Jones, was up next. Durocher didn’t want to put Jones aboard to close up the empty base as the potential winning run with Art Shamsky, a lefthanded hitter with power, due up behind Jones. So Jenkins would pitch to Jones, starting him with a curve ball that “got more of the plate than Jenkins wanted,” Coffey writes, and Jones slashed a double to left, tying the game at once.

Jenkins then put Shamsky aboard to pitch to weak hitting Mets infielder Wayne Garrett instead. He got Garrett to ground out to Beckert at second, but the grounder set up second and third again. Two outs and Kranepool, another lefthanded hitter and the last remaining Original Met, was next. Mets catcher J.C. Martin, a lefthanded hitter with an oh-so-sterling .258 on-base percentage to that point, and whose 1969 batting average against righthanders was lower than that against lefthanders, was due up after Kranepool.

With the winning run already aboard, Durocher could have put Kranepool on and gotten the advantage of Martin’s reverse split. But he let Jenkins pitch to Kranepool. And at first it looked like Jenkins would have the best of it, getting ahead of Kranepool 1-2 on a diet of breaking balls at the outer edges. Knowing he wouldn’t see a proper strike, Kranepool got what he expected, another off-speed pitch away.

When not ripping a hapless teammate after max-effort misplays, Ron Santo’s heel-clickings after Cub wins made him the most frequent Cub target for retaliatory brushback pitches.

With Jones running from third on contact Kranepool reached for the pitch and lofted it on a soft line over shortstop. Kessinger chased it into supremely short left field but couldn’t reach it. The ball hit the grass. Jones hit the plate running. Shea Stadium exploded after the 4-3 win the Mets all but embezzled out of the Cubs. Nobody heard Durocher thundering that his three-year-old could have gotten to Kranepool’s quail.

All hell broke loose after midnight that night when, Clarebaut related, a friend of Santo’s rang his New York hotel room around 3 a.m. to tell him the Sun-Times let him have it over his public criticism of Young. Santo was no shrinking violet: he called a press conference for the next afternoon and apologised.

It was more than the hapless Young got from Durocher, which was nothing. Durocher never mentioned the game in the chapter on those Cubs in his memoir Nice Guys Finish Last.

Still claiming Young’s day at the plate got into his head in the field, Santo added, “I know this is true because it has happened to me. I have fought myself when I wasn’t hitting and, as a result, messed up in the field. But I know I was wrong. I want everyone to know my complete sincerity in this apology.” Too much, too little, too late.

Santo took a back seat to few for giving Durocher the benefit of the doubt, but even he admitted in due course, “He brought us closer to a pennant than anyone else had in a generation. But he also brought disruption and chaos.”

Indeed. When a writer asked whether he thought about resting some of his regulars, Durocher lost it. He called a team meeting on the spot demanding to know whom among his players were tired—and the players, knowing only too well that Durocher would accuse fatigued and injured players of being quitters, nobody said a word.

And one of the reasons the Mets went the distance was their own completely opposite manager. Gil Hodges played for Durocher in Brooklyn and knew Durocher’s blustery style only too well. He also had an instinct Durocher lacked: he monitored his players’ health judiciously, kept his regulars regular but fresh, kept his bench and role players alert and prepared, and kept the Mets in better shape for their magnificent 44-17 season finish.

If Hodges managed Don Young and thought Young loafed on one fly and gave up on the other, he would have buttonholed Young privately first and asked what happened out there first before rendering a verdict Hodges would never have given in public or with insults at all. If Hodges knew Young gave top effort, he would have reviewed the plays with Young and gotten him to think aloud about improving his readings and jumps on the ball.

If only.

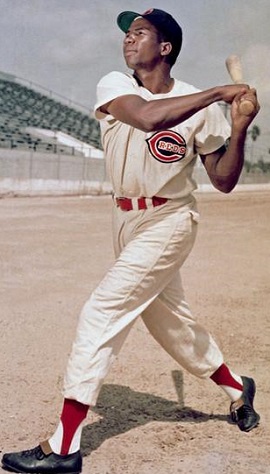

Because when Sports Illustrated caught up to Ernie Banks in 2014, two years before his death, Banks was asked which single moment he thought introduced the poison into the 1969 Cubs’ well. The Hall of Famer whom Leo Durocher disliked upon arrival in Chicago but couldn’t get rid of because he was still the spiritual face of the Cubs didn’t mince words:

They say one apple can spoil the whole barrel, and I saw that. Before going to New York to play the [8 July game] against the Mets, I went to different players on our team and told them, ‘We’re going to New York, and when the game is over, there’s going to be more media than you’ve ever seen in the clubhouse, so watch what you say.’ So we got to New York, and lose the first game. Don Young dropped a fly ball, and that was it. We came into the locker room. I was next to Santo, and he just went crazy. Young was so upset, he ran out. [Coach] Pete [Reiser] had to bring him back. I had never seen something so hurtful.

Banks said the Cubs began falling apart factionally from there. Marry that to burnout, both of the regular players and the pitching staff, including bullpen bull Regan, plus Durocher’s long-lost sense of perspective, and that—after spending enough of the first half looking like they had the National League East in a safe deposit box—was the story of the ’69 Cubs’ collapse. (The Cubs from 1 August-1 October: 27-29.)

Durocher went from bad to worse after that, little by little, until he either quit or was fired during the 1972 season. Santo called it “a turbulent clubhouse mess.” He might have been the Cubs’ winningest post-World War II manager by the time he left, but he also hamstrung the club. The Cubs wouldn’t even see .500+ season results again for another twelve years after Durocher left. You could almost predict Opening Day fans whipping up placards as the first pitch was thrown: “Wait ’till next year!”

Young ended up spending 1970-72 in the minors, his once fine throwing arm betraying him, then left baseball and went on with his life, living free spiritedly and working his way across the country. Every so often he signs photographs, caps, or baseball cards for fans who catch up to him.

Three 1969 Cubs—Banks, Jenkins, and Billy Williams (the only Cub regular who didn’t wilt down the stretch)—ended up in the Hall of Fame. So did two 1969 Mets—Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan, though Ryan didn’t exactly look like a Hall of Famer at the time despite a few performances showing the potential.

Durocher and Santo also ended up in the Hall of Fame—posthumously. Santo at least had the playing record to justify his election; he was the game’s best all-around third baseman after Eddie Mathews faded and before Mike Schmidt came into his own. He may well have had to wait because, no matter his retirement of charity, popularity as a Cub broadcaster, and lifelong courageous battle against diabetes, he’d been a prickly personality as a player with a number of hassles comparable to if not quite as fateful as the Young incident.*

But we’ve known for almost two decades now, for dead last certain, that Durocher cheated the 1951 Giants into a pennant race comeback that forced the legendary three-game playoff they won. Between that, his single World Series championship in a cumulative 24 years worth of major league managing, and his dessication of a Cubs team that should have finished what they started in 1969, how did he get into Cooperstown?

He was famous? So were Gene Mauch and Fred Hutchinson. So was Gil Hodges. But that trio didn’t have the Lip’s penchant for ingratiating himself with the show business glitterati. Somehow, some people are crazy enough to think that you need more than going on the air any time you please or being Frank Sinatra’s buddy pal to qualify for the Hall of Fame.

The 1969 Cubs settled for being Claerbaut’s “Greatest team that didn’t win.” The 1969 Mets settled for becoming the last but most successful of three 1960s miracle teams. (The others: the 1961 Reds and the 1967 Red Sox, neither of whom won their World Series.) And, the far better side of baseball mythology.

* Santo’s 1969 habit of clicking his heels on the field after Cub wins so annoyed opponents that by his own admission he became the Cubs’ most frequent target for knockdown and retaliation pitches. When Mets coach Joe Pignatano called him “bush!” for it before a game, Santo flipped him the bird. But when exchanging lineup cards with Hodges before that game, as the Cubs’ team captain, Santo pleaded, “Tell Piggy the only reason I click my heels is because the fans will boo me if I don’t.”

Hodges didn’t buy it for a minute. “You remind me of [Mets relief pitcher] Tug McGraw,” the Mets’ skipper replied. “When he was young and immature and nervous, he used to jump up and down too. He doesn’t do it anymore.” And Santo eventually wrote in his memoir, “The rest of the league wasn’t so enthralled. Once they started catching onto my act, the fastballs seemed to get a lot closer to my head. The brushback pitches seemed to come a lot closer to my chin.”

And other places. On 8 September, Cub starter Bill Hands drilled Agee in the bottom of the first and Koosman, not hesitating a single degree, drilled Santo in the wrist in the top of the second. It cost Santo his power for the season; he hit only two more of his 29 home runs the rest of the way, including on closing day 2 October—against the Mets, who could afford the 5-3 loss since they won the NL East by eight games.

Oh, every now and then I work a small one just to keep My hand in. My last miracle was the 1969 Mets. Before that, I think you have to go back to the Red Sea. Ahhhhh, that was a beauty!

Oh, every now and then I work a small one just to keep My hand in. My last miracle was the 1969 Mets. Before that, I think you have to go back to the Red Sea. Ahhhhh, that was a beauty!