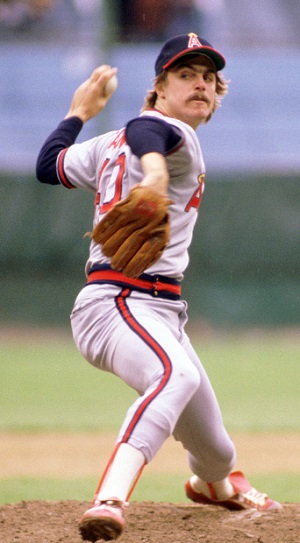

Frank Tanana—despite pre-Show injuries he was allowed to throw 1055.2 major league innings and 71 complete games from ages 20-23. Are you still surprised he was broken into a journeyman by 25?

When Hall of Famer Dennis Eckersley threw a no-hitter for the Cleveland Indians on today’s date in 1977, he beat the California Angels, 1-0. The Angels opposed him with lefthander Frank Tanana going the distance against him. And all Hall of Fame writer Tracy Ringolsby can think about is both pitchers going the distance in the same game.

Based on a pair of tweets Saturday morning, the anniversary of the Eckersley no-hitter, Ringolsby thinks Tanana’s arm and shoulder issues—the ones that turned him from a howitzer to a journeyman seemingly overnight—were caused by nothing more than an unwarranted change in his mechanics.

He couldn’t bring himself to acknowledge that the Top Tanana was badly overworked by age 24-25.

Dennis the Menace had to work his tail off for the no-no, the only run scoring on a first-inning triple and a squeeze bunt. He nailed twelve strikeouts and walked only one, while Tanana—who led the Show in strikeouts and strikeout-to-walk ratio two seasons before—struck out six and scattered five hits.

“You mean a pitcher can work nine innings in the same game? Wow,” tweeted Ringolsby Saturday, recalling the game. A short time later, a p.s. tweet: “Tanana—best LH’d pitcher I have seen before arm problem created when after establishing himself as dominating a pitching coach decided he needed to change his mechanics. Body had adapted to old method and balked at new approach.”

Not quite. Tanana had issues that prompted the change in the first place, elbow and shoulder issues a genuinely smart baseball person or team would have spotted and adjusted to overcome from almost the word go. Tanana was 23 years old in 1977 and worked beyond the bone before that season began.

It’s true that he enjoyed too much of the high life in those younger seasons. Also by his own eventual admission, he was as cocky as the day was long. With apologies to Jim McCarty, the drummer for the Yardbirds who said it about their guitarist Jeff Beck, it was often said that Frank Tanana was one of the American League’s hottest young guns and many were inclined to agree with him.

Then he became the journeyman nobody—including himself—predicted he’d become when he first hit the American League running at age 20. In fact, you can ask if the Angels should have been surprised, after all. Tanana didn’t exactly come injury-free in the first place.

As a high school senior, he injured his shoulder throwing sidearm to a batter, pitched with the injury the rest of his senior season, but took himself out of a championship game after four innings because the pain was too great. Then he dealt with shoulder tendinitis in his first minor league season. Was the Angels’ radar miscalibrated?

Pay close attention to what follows from that with a pitcher who already had a history of shoulder trouble. Now, tell me what turned Tanana from a Hall of Famer in the making (maybe you had to be there, but that’s just about how he and they talked about this kid) to a mere survivor living on smarts instead of a nasty fastball and deceptive curve ball for the last sixteen years of his career:

Age 20—268.2 innings pitched, 12 complete games in 35 starts; 3.12 ERA, 3.49 fielding-independent pitching (FIP); pitched better than his 14-19 won-lost record. If you can tell me what a 20-year-old with an early injury history is doing pitching that many innings at all (he averaged seven innings plus per appearance), never mind his first major league season, you’re a better manperson than I.

Age 21—With a 2.62 ERA and a 2.49 FIP (leading the American League), Tanana pitched arguably the best season of his life. He also had 16 complete games in 33 starts and 257.1 innings pitched. That makes 526 innings and 28 complete games in two seasons before he was 22.

Age 22—Tanana led the majors in walks/hits per inning pitched (WHIP) with 0.99 and led the American League with a 3.58 strikeout-to-walk rate. (His 3.68 the year before led the entire Show.) Now the bad news: He pitched 288.1 innings and threw 23 complete games in 34 starts.

That’s 51 complete games in three seasons from ages 20-22, not to mention 814.1 innings pitched, in a time frame in which a sensible organisation would be developing a pitcher that age reasonably. The star-crossed Angels had nobody substantial behind Tanana and Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan to relieve the pitching workloads, and they weren’t exactly run producing machines enough to let Ryan and Tanana pitch with less mental stress, while we’re at it.

So they worked the pair almost unconscionably. Now, repeat: Nolan Ryan’s was one-of-a-kind durability. In almost any baseball era. You cannot use Ryan’s endurance as the measurement for every professional pitcher. No two of them are built the same, and we’re not talking mental makeup. No two pitchers have the same arm, shoulder, and body capacities.

Whether Tanana or the Angels or both believed Tanana could be that kind of durable despite his early injuries, what they believed wasn’t the same as what was proved. The warning signs were there early and often. At age 20 Tanana even pitched through a bothersome elbow for a seven-loss streak, and it’s not unlikely that he dealt with elbow and shoulder discomforts consistently enough the next few years.

Now comes Tanana’s age-23 1977. The good news: he led the American League with seven shutouts and a 2.54 ERA, and his 2.97 FIP still had him at the top of the league’s pitching line. But also came the bad news: He pitched 20 complete games including fourteen straight—and in three of the fourteen he worked on only three days’ rest, and in two of which he pitched ten and eleven innings.

He also developed tendinitis in his left arm. His season ended early. So did his life as the Top Tanana.

Because look what happened in 1978. His FIP jumped over 3.00 and never came below that mark again. He feared that elbow tendinitis returning and altered his motion to block any more such stress . . . only to develop shoulder tendinitis. That got him shut down near season’s end and cost him two months in 1979.

Seventy-one complete games, 1055.2 innings from ages 20-23 (it works out to an average 264 innings a year), and several times pitching through elbow or shoulder pain. (Pitch counts weren’t kept then. But it shouldn’t surprise you if it’s proven Tanana might have thrown 120+ pitches or worse in too many of those games.) Should we really have been surprised that Tanana was practically broken in half before he was 25?

All that and more knocked the cockiness right out of him as well as the early weight of that fastball and curve ball. (The murder of his Angels teammate Lyman Bostock in 1978 also affected him deeply.) He surrendered his former wild style off the field—the style that once prompted him to say the best night of his life was “last night” and a teammate to chime in, “I saw her. And he’s right.”

Tanana swapped all that for life as a gainfully employed back-end-of-the-rotation man and a spiritual, happily married father and grandfather who swore his time and quiet success with his hometown Detroit Tigers—after bouncing from the Angels to the Boston Red Sox to the Texas Rangers—was what really turned his career around.

Eckersley survived a battle with the bottle to remake his career from eventually fading starter to lights-out closer who pioneered the single-inning save machine under his Hall of Fame manager Tony La Russa. A different physical specimen, Eckersley from ages 20-23 pitched 901 innings himself but he’d been built up gradually, from 186.2 to 199.1 to 247.1 to 268.1. He wasn’t ridden terribly hard from the beginning.

Tanana managed to survive on the mound as a useful, deceptive junkballer until he was 39. His mechanical change didn’t cause the arm and shoulder trouble, Mr. Ringolsby. The arm and shoulder trouble inspired the mechanical change. It remains to wonder what if Tanana was managed more prudently as a young howitzer. And, when the old school will finally wake up and learn.