Kyle Tucker’s seventh-inning strikeout seemed to take what remained of the Cubs’ wind away Saturday night. (TBS television capture.)

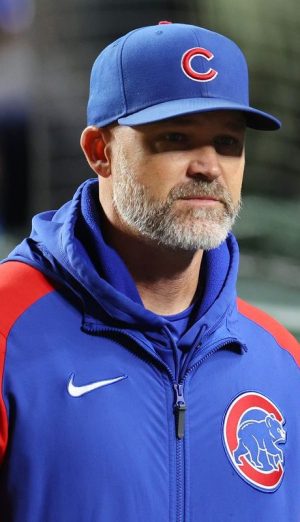

“It’s really the only inning you could talk about,” lamented Cubs manager Craig Counsell about the top of the sixth, after National League division series Game Five. “We just didn’t do much.

“We had six base runners. You’re going to have to hit homers to have any runs scoring in scenarios like that,” Counsell continued. “They pitched very well. I mean, they pitched super well and we didn’t.”

“They” were the Brewers, whom Counsell used to manage, until he reached managerial free agency and the Cubs decided to dump David Ross for no reason better than that Counsell became available. Cubs president of baseball operations Jed Hoyer admitted as much earlier this month.

Two second-place National League Central finishes and one division series loss later, Cub fans could be forgiven if they think it’s been karma for the manner in which Ross was vaporised. The Brewers won Game Five, 3-1, with 90 percent pitching depth, five percent unusual slugging, and maybe five percent karma-the-bitch.

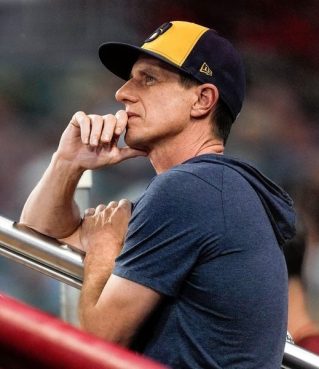

Until, that is, they review the seventh inning in American Family Field Saturday night. First and second, nobody out, and Kyle Tucker—the man for whom the Cubs traded three to the Astros last December, in perhaps the signature moment that explains why they made that trade—coming to the plate.

He faced Aaron Ashby, the nephew of former major league pitcher Andy Ashby, and possibly the best relief pitcher on the Brewers staff. (Regular season: 2.16 ERA; 2.70 fielding-independent pitching rate.) His Cubs were down only 2-1. He got ahead of Ashby three balls, no strikes. Michael Busch (leadoff single) and Nico Hoerner (hit by a pitch) leaned away from second and first itching for a reason to take off.

The odds were in favour of them getting that reason momentarily. Tucker had spent the first three games of the division series as a singles hitter, but in Game Four he finally unloaded, blasting a leadoff home run in the bottom of the seventh. Maybe, despite an early strikeout and a subsequent ground out Saturday night, Tucker’s power strokes were back from the fixit shop.

Big maybe. Ashby pumped a pair of bullets Nolan Ryan himself might have applauded. Tucker swung through both of them.

Then Brewers manager Pat Murphy brought rookie righthander Chad Patrick into the game. Patrick, a righthander with seven minor league seasons behind him and not one Show appearance until the Brewers called him up from AAA Nashville for this year. He got Seiya Suzuki—who’d tied the game at one in the top of the second, when he answered William Contreras’s first-inning solo home run with a bomb of his own against Jacob Misiorowski—to drive one to left that found Jackson Chourio’s glove. He dropped strike three called in on Ian Happ.

Not one Cub came home in that inning or the rest of the way. The Brewers added one more in the seventh, when Brice Turang took Cub reliever Andrew Kitteredge over the right center field fence.

“I was looking up at the heavens to Bob Uecker,” said Brewers general manager Matt Arnold, referencing the beloved late Hall of Fame broadcaster and wit, who’d become as much a face of the Brewers as any player in their history until his passing last January. “Like, during the game, I’m like, ‘Bob, we need you’.”

“I must be in the front row,” Uecker must have said from his roost in the Elysian Fields.

He must have. This team had baseball’s best regular season record this year but entered the division series with a string of failure to get past their first postseason stages for five out of the previous six seasons. They were still recovering from their former closer Devin Williams, now a reliever and frequent hate object (by their own fans) for the Yankees, serving a pitch Mets first baseman Pete Alonso demolished like a munitions expert in the deciding wild card series game last year.

This time, they had to recover from the Cubs, their next-door-state rivals, coming back from a 2-0 game deficit.

This time, they made it. So far.

They have a National League Championship Series date with the Dodgers. They secured the date doing what enough people thought they couldn’t do if it meant paying the ransoms for their kidnapped families: slug. Contreras and Turang were joined by Andrew Vaughn in the fourth, blasting a full-count service from Collin Rea into the left field seats.

They even did it with men who weren’t even topics on last year’s team. Vaughn and Patrick were joined in that club by Misiorowski, who relieved Game Five’s opening closer Trevor Megill, surrendered only Suzuki’s second-inning smash, but otherwise worked spotlessly for his four innings. In what turned out a bullpen battle, the Brewers pen was just that much more efficient than the Cubs pen, which also deployed one starter (Rea) among a group of bulls.

Vaughn running out his fourth-inning bomb. (TBS television capture.)

And, boy, is the deal that brought Vaughn from the pathetic White Sox to the Brewers looking better every hour. It happened when the Brewers elected to move Aaron Civale from the starting rotation to the bullpen, and Civale responded with a spoken desire to play somewhere else if that was the case. Be careful what you wish for, was the answer . . . and Civale went from a contender to a basement dweller just like that, in early June, with Vaughn—once a first-round draft pick, demoted to the farm a month earlier—coming aboard.

Therein lies a distinction between these Brewers and the Cubs they just turned aside. The Brewers don’t have Cub money, but they don’t let that stop them from constant upgrade searching when necessary. The Cubs have Cub money. But they’d rather undergo root canal without anesthetic than spend it. And they lack the Brewers’s bargain basement ingenuity. They haven’t yet figured out that you don’t have to shop at the Magnificent Mile all the time. You can find amazing upgrades at Lots 4 Less.

How will these Brewers be perceived going into an NLCS against those Dodgers? Contradictorily, of course. The Brewers swept the Dodgers in their regular-season series, 6-0. But there’ll be more than enough who think the Dodgers will still be the overdogs. Even if the Dodgers’ NLCS ticket was stamped by a horror of a throwing error by Phillies relief pitcher Orion Kerkering in Game Four of their division series.

But how will these Cubs be perceived going into winter vacation? Not too favourably, after all, one fears. The top of their lineup acquitted themselves well enough, particularly Busch with three of his four division series hits clearing the fences and Nico Hoerner with his hits in each game and his team-leading .476 postseason on-base percentage. But the bottom of the lineup disappeared. The collective slash line of the Cubs’ bottom five? .120/.215/.205.

And they’re likely enough to move forward without Tucker, who becomes a free agent and who’s perceived widely enough as thinking about moving on. Even if this usually un-expressive fellow who prefers to let his game do his talking calls it “an honour” to play with this group of Cubs.

That group of Cubs needs a small, not major bullpen remake, and they need to romance and re-sign Tucker, whom they could and should have extended during the second half of the season. But maybe the Cubs need a front-office overhaul, too. The kind that brings in persuaders who can convince the Ricketts family that it’s time to open the purse strings but think about trying Lots 4 Less after that one Magnificent Mile splurge.

Finishing with their best regular-season record since 2018 shouldn’t be enough. Three straight second-place NL Central finishes shouldn’t be enough. But maybe watching the Brewers go forth and tangle honourably with the ogres of the National League West will give these Cubs—and their ownership that’s as endowed as Mercedes-Benz but prefers to drive indiscriminately off the Chicago Auto Warehouse lot—more than a little pause.

The Brewers couldn’t care less for now. They’re enjoying their first postseason series clincher since 2018, the year they shoved the Rockies aside in a division series sweep. And if they wanted any further incentive, they got it from cynics and Cub fans alike who snarked that they hadn’t won a postseason series yet as they took the Cubs on. As if their round-one bye meant squat.

So who has the next-to-last laugh now?

Once upon a time, the early rock and roll era included a novelty hit, “Beep Beep,” in which a little Nash Rambler (I always presumed it to be the anti-classic, two-seat Metropolitan) went tire-to-tire with a Cadillac in a daring little race. The Brewers are the Nash Rambler about to go tire-to-tire with the Dodgers’ Cadillacs.

And, unlike “Beep Beep’s” challenger, they know how to get themselves out of second gear.