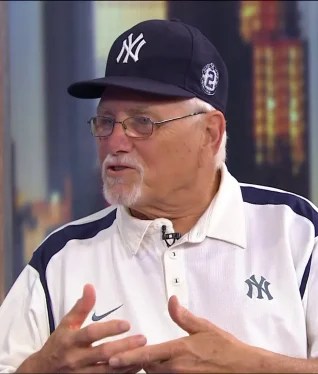

Aaron Boone fingers the culprit impressionist who really barked at umpire Hunter Wendelstedt after Boone kept his mouth shut following one warning. (YES Network capture.)

Umpire accountability. There, I’ve said it again. The longer baseball government refuses to impose it, the more we’re going to see such nonsense as that which Hunter Wendelstedt inflicted upon Yankee manager Aaron Boone in New York Monday.

The Yankees welcomed the hapless Athletics for a set. Wendelstedt threw out the first manager of the game . . . one batter and five pitches into it. And Boone hadn’t done a thing to earn the ejection.

Oh, first Boone chirped a bit over what the Yankees thought was a non-hit batsman but was ruled otherwise; television replays showed A’s leadoff man Esteury Ruiz hit on the foot clearly enough. Wendelstedt got help from first base umpire John Tumpane on the call, and Tumpane ruled Ruiz to first base.

The Yankees and Boone fumed, Wendelstedt warned Boone rather loudly, and Boone kept his mouth shut from that point.

Until . . . a blue-shirted Yankee fan in a seat right behind the Yankee dugout hollered. It looked and sounded like, “Go home, ump!” It could have been worse. Fans have been hollering “Kill the ump!!” as long as baseball’s had umpires. George Carlin once mused about substituting for “kill” a certain four-letter word for fornication. His funniest such substitution, arguably, was “Stop me before I f@ck again!” The subs also included, “F@ck the ump! F@ck the ump!”

Neither of those poured forth from the blue-shirted fan. Merely “Go home, ump!” provoked Wendelstedt to turn toward the Yankee dugout and eject . . . Boone, who tried telling Wendelstedt it wasn’t himself but the blue shirt behind the dugout. “I don’t care who said it,” Wendelstedt shouted, and nobody watching on television could miss it since his voice came through louder than a boat’s air horn and, almost, the Yankee broadcast team. “You’re gone!”

I don’t care who said it.

“When an all-timer of an ejection happens,” wrote Yahoo! Sports’ Liz Roscher, “you know it, and this qualified.”

There was drama. There was rage. There was the traditional avoidance of blame on the part of the umpire. It’s a classic example of the manager vs. umpire dynamic, in which the umpire exercises his infallible and unquestionable power whenever and wherever he wants with absolutely zero accountability or consequences of any kind, and the manager has no choice but to take it.

Bless her heart, Roscher actually used the A-word there. And I don’t mean “and” or “absolutely,” either. She also noted what social media caught almost at once, that Mr. Blue Shirt may have mimicked Boone well enough to trip Wendelstedt’s trigger even though the manager himself said not. one. syllable. after the first warning.

May. You might think for a moment that a manager with 34 previous ejections in his managing career has a voice the umpires can’t mistake no matter how good an impression one wisenheimer fan delivers.

This is also the umpire whom The Big Lead and Umpire Scorecards rated the third-worst home plate umpire in the business last year, worsted only by C.B. Bucknor (second-worst) and Angel (of Doom) Hernandez (worst-worst). I’ve said it before but it’s worth repeating now. Sub-92 percent accuracy has been known to get people in other professions fired and sued.

A reporter asked Boone whether the bizarre and unwarranted ejection was the kind over which he’d “reach out” to baseball government. “Yes,” the manager replied. “Just not good.”

Good luck, Skipper. Umpire accountability seems to have been the unwanted concept ever since the issue led to a showdown and a mass resignation strategy (itself a flagrant dodge of the strike prohibition in the umps’ collective bargaining agreement) that imploded the old Major League Umpires Association in 1999.

The Korean Baseball Organisation is known for its unique take upon umpire accountability. Umps or ump crews found wanting, suspect, or both get sent down to the country’s Future Leagues to be re-trained. Presumably, an ump who throws out a manager who said nothing while a fan behind his dugout barked would be subject to the same demotion.

If the errant Mr. Blue Shirt really did do a close-enough impression of Boone, would Wendelstedt also impeach James Austin Johnson over his near-perfect impressions of Donald Trump?

Well after the game ended in (do you believe in miracles?) a 2-0 Athletics win (they scored both in the ninth on a leadoff infield hit and followup hitter Zack Gelof sending one into the right field seats), Wendelstedt demonstrated the possibility that contemporary baseball umpires must master not English but mealymouth:

This isn’t my first ejection. In the entirety of my career, I have never ejected a player or a manager for something a fan has said. I understand that’s going to be part of a story or something like that because that’s what Aaron was portraying. I heard something come from the far end of the dugout, had nothing to do with his area but he’s the manager of the Yankees. So he’s the one that had to go.

The fact that an umpire can order stadium personnel to eject fans or even toss a loudmouth in the stands himself (it happened to Nationals GM Mike Rizzo courtesy of now-retired Country Joe West, during a pan-damn-ic season game in otherwise-empty Nationals Park) seems not to have crossed Wendelstedt’s mind. The idea of saying “I was wrong” must have missed that left toin at Albuquoique.

Major league umpires average $300,000 a year in salary. If I could prove to have a 92 percent accuracy rate and learn to speak mealymouth, I’d settle for half that.