If there is one thing I am absolutely sure of, it is that it was not a two-man show. We all did it. And let me be very clear that I am not denying my responsibility, because we were all responsible . . . Everyone who was part of the team from around mid-May until the end of the season, we are all responsible.

—Alex Cora, bench coach for the 2017 Houston Astros.

Would you believe a high school baseball game unwittingly inspired major league baseball’s first known extralegal sign stealer? An 1899 Phillies utility player turned third base coach was playing the ponies in New Orleans, watching the nags through binoculars, when he spotted something in the distance through them: the hands of a catcher flashing signs in that high school game.

From there, Pearce Chiles devised a system whereby one man would post behind the outfield fence with binoculars to decipher signs, then tap pulses to a device embedded below Chiles’s third base coaching line. After Reds shortstop Tommy Corcoran smelled the proverbial rat and unearthed the rig, the Phillies’ team batting average sank by 44 points.

If you must, call Chiles the great-great-great grandfather of Astrogate. SNY writer Andy Martino just about does, in his sober, engaging, and freshly troubling Cheated: The Inside Story of the Astros Scandal and a Colourful History of Sign Stealing. (New York: Doubleday; 270 p, $28 [$25 on Amazon].) It’s a freshly published reminder that, whether or not Astro fans or anyone else like it, Astrogate will not disappear soon into history’s recesses.

Nor should it. And this is while the forthcoming Winning Fixes Everything: The Rise and Fall of the Houston Astros—by Evan Drellich, one of the two Athletic writers (Ken Rosenthal was his partner) who sent Astrogate to the point of no return, when they finally had a player with direct knowledge (pitcher Mike Fiers) go on public record—may be delayed from its original planned August publication.

“Were the Astros part of a long tradition of sign stealing? Or were they outliers, worse than anyone else in history?” asks Martino, a ten-year veteran of baseball journalism now an SNY reporter. Then, he answers—yes, and no: “The answer is, well, both. What Houston did was the logical extension of more than a century of teams looking for an edge on the fringes of legality. But it was also new and different than anything that came before it.”

It also soiled irrevocably a championship run that gave a Houston battered badly by Hurricane Harvey an immeasurable spiritual lift. The team who put its collective arms around the ravaged city made it resemble fools for rooting for a team whose high-tech cheating came from the amoral front office down.

“[T]he team had access to technology that no other generation of cheaters could use,” Martino writes. ” . . . This was a twenty-first-century scam, pulled off by a group of people with the right blend of intelligence and moral flexiblitiy.”

Then, he quotes a baseball legend I’ve quoted a time or two through the entire Astrogate aftermath, a legend often accused of his own amorality until that and much else was almost completely debunked—Ty Cobb, who wrote in 1926 that “mechanical devices worked from outside sources” was “reprehensible and should be so regarded.”

The time-tested ways and means of legitimate (if only slightly unethical) on-base, on-field sign decoding have always had their experts. They’ve caught onto anything, not just the signs from catchers to pitchers, but assorted little hints in assorted moments, from catcher positioning when receiving certain pitchers to pitchers’ gestures when preparing to throw certain pitches.

In this century, Martino writes, they’ve included such men as Hall of Famer Roberto Alomar plus Carlos Beltran, Carlos Delgado, Joe Carter, Alex Cora, Shawn Green, Alex Rodriguez, and others. As Blue Jays teammates, Delgado and Green learned from manager Cito Gaston and from Alomar and Carter; Beltran learned from Delgado when they were Mets teammates. They were only too happy to pay it forward and teach teammates to come such intelligence arts.

Those men would use that kind of intelligence on the bases and even compile their own post-game logs (Delgado especially was such a player) on the various tells and reveals they’d discovered. So long as they did nothing in-game other than basepath espionage, all they had to do was hope the opposition didn’t catch on right away and switch signs or correct tells.

They weren’t operating the kind of high-tech cheating that came from Astros front-office intern Derek Vigoa, who convinced cold-blooded, results-before-humanness general manager Jeff Luhnow about a computer algorithm he’d developed for sign decoding called Codebreaker—but who warned to no avail that using it pre- and post-game was one thing but in-game was illegal.

The kind that gave Cora—now the Astros’ bench coach, with Beltran aboard as the team’s designated hitter and unofficial player mentor—an unexpected a-ha! when he discovered the high-speed, thousand-frame-a-minute Edgertronic camera. Until that discovery, Cora and Beltran were merely well-oriented, long-experienced students of what Paul Dickson’s study of the craft and its abusers alike called The Hidden Language of Baseball.

By the time Cora and Beltran began brewing their side of the Astro Intelligence Agency, more than a few other teams figured out a way to help baserunners send stolen pitch intelligence to their teammates at the plate: the replay room. The Astros weren’t wrong when they spoke publicly about those.

But the Astros played the whatabout game to deflect from their having gone above and beyond even the replay room reconaissance rings. Even after rumour and speculation graduated to fact and they were exposed for all time as transdimensional high-tech cheaters.

Those who still don’t get the difference between using established replay rooms to augment old-school gamesmanship (remember: the 2018-19 Red Sox’s replay room reconnaissance ring still depended on having a baserunner to send a batter the purloined numbers) and an illegal real-time camera sending signs should be ignored roundly.

MLB finally accepted instant replay, and installed replay rooms in the first place with the best of intentions, Martino reminds us. The entire sport was mortified by first base umpire Jim Joyce making a wrong safe call to deny Tigers pitcher Armando Gallaraga a perfect game on what should have been the final out. The result was both a helpmate and an unintended headache.

Boys will be boys, even in the 21st Century. Even the best-intentioned of newfangled solutions to immediate or time-worn problems find themselves at the mercy of boys being boys. When they’re the highest of high-tech solutions, there will be and there were boys being boys figuring out how to put them to nefarious service.

Martino insists quickly and supports in detail that that the most notorious illegal, off-field-based sign stealers who preceded or accompanied the 2017-19 Astros didn’t and still don’t justify the AIA. Quickly enough that it’s Cheated‘s second chapter, titled “No, the 1951 Giants Don’t Justify the Astros.”

Not those Giants, whose manager Leo Durocher installed a coach with a hand-held Wollensak spyglass in the clubhouse above the Polo Grounds’ center field to steal signs, enabling their stupefying comeback from thirteen games out of first place and, in due course, the pennant playoff triumph.

Neither do such telescopic cheaters as the 1910 New York Highlanders (exposure of which cost manager George Stallings his job), the pennant-winning 1940 Tigers (using a hunting rifle scope to steal signs from the outfield seats) or the 1948 World Series-winning Indians. (Courtesy of Hall of Famer Bob Feller’s Wollensak-like spyglass, brought inside the Municipal Stadium scoreboard to steal signs down the stretch.)

Those already went above and beyond the time-honoured ways and means of on-field sign stealing and discoveries of pitch tipping and other “tells” and “reveals” exploitable by the excessively observant. The AIA made the ’10 Highlanders, the ’40 Tigers, the ’48 Indians, and even the ’51 Giants resemble kids playing Spy vs. Spy.

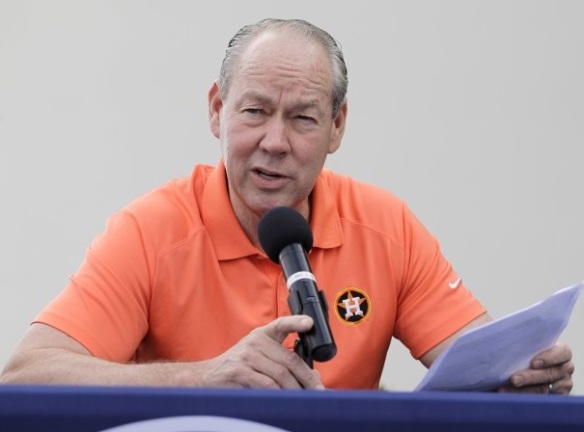

This was a genuinely talented, well-built team surrendering hook, line, and stinkers to the high-tech temptations. With pliant, “conflict-averse to a fault” manager A.J. Hinch—burned by his first managing job in Arizona, where he clashed with veterans suspicious of his contemporary, information-augmented style—bent on fostering “a largely positive environment” with vets and youth alike in his clubhouse.

Enough that he felt without power to stop the high-tech cheaters in his own dugout.

Not every Astro was completely on board. Martino argues that second base star Jose Altuve objected vocally after hearing banging while he batted, even yelling at teammates in the dugout to knock it off. Neither did Altuve wear any kind of buzzer on his body. Veteran reserve catcher Brian McCann (since retired) and right fielder Josh Reddick (now with the Diamondbacks) also demurred.

Those who accused Mike Fiers of just keeping his mouth shut until he was an ex-Astro might be surprised to discover Martino recording very plausibly what other reporting since has affirmed: Fiers actually did object to the AIA while he was an Astro, before passing warnings to beware on to his eventual Tigers and Athletics teammates.

We’ve known long enough that the A’s filed complaints with the commissioner’s office about their suspicions that the Astros were up to things above and beyond old-school on-field gamesmanship. We’ve also known long enough that Fiers finally went on the record after too many other writers couldn’t convince their editors to let them run players’ suspicions without disclosing their identities.

Rob Manfred has earned most of the criticism he’s garnered during his term. But Martino records that he hoped he could get the deep Astrogate story without giving players immunity. When that proved implausible, Martino writes, the commissioner finally resigned himself and, with the players union’s agreement, got AIA players and personnel past and incumbent to talk—so long as the players got blanket immunity.

That was then, this is now. Manfred, the owners, and the players union have since agreed that players caught performing Astrogate-like electronic espionage can be suspended without pay and without credit for MLB service time.

Manfred’s January 2020 report, of course, named only one player publicly—Beltran, whose involvement cost him his new job managing the Mets . . . before he got to manage even a spring training game. Cora resigned before he could be fired as the Red Sox’s manager—but was brought back after last season. His confessional to ESPN reporter Marly Rivera a year ago probably went a long way toward rehabilitating him enough to get that second chance.

Hinch sat out his suspension, then got a second chance managing the rebuilding (and next-to-last-place) Tigers. Some say that’s cruel and unusual punishment for Hinch, who spoke candidly to Sports Illustrated‘s Tom Verducci last year about his failure to contain and dissipate the AIA.

A year after the infamous break-in, Richard Nixon gave a speech in which he insisted, a little testily, “One year of Watergate is enough.” Nixon was wrong then. Those who think a little over a year and a half of Astrogate is enough are wrong now.

Even with only five members of the Astrogate teams remaining on the club, their facing pan-damn-ically delayed fan fury over the tainted champions is one example. Martino’s book is another. Drellich’s will be a third. With apologies to Professor Berra, when it comes to Astrogate literature it won’t be over until it’s over.