The White Rat on the Cardinals’ bridge. Winning three pennants and a World Series before a later, lackluster edition prompted him to walk.

It’s forgotten often enough, but Whitey Herzog was supposed to be the man who succeeded Gil Hodges on the Mets’ bridge if that time should have come. It came when Hodges died of a heart attack during spring training 1972. But the White Rat ran afoul of the Mets’ patrician chairman of the board M. Donald Grant well before that.

Herzog, who died Monday at 92, ran the Mets’ player development after one season as the Mets’ rather animated third base coach (1966) and one managing in the Florida Instructional League (1967). He was part of bringing the Mets such talent as pitchers Gary Gentry and Jon Matlack, first baseman John Milner, third baseman Wayne Garrett, and outfielders Amos Otis and Ken Singleton.

But his role in the first try at bringing eventual Miracle Met outfield acrobat Tommie Agee to the Mets from the White Sox got Herzog in big trouble with Grant. Then-Mets general manager Bing Devine, who’d hired Herzog in the first place, led a Mets contingent to the 1967-68 winter meetings and cobbled a deal to get Agee in exchange for veteran outfielder Tommy Davis and a decent but not spectacular relief pitcher named Don Shaw.

Shaw posted a 2.98 ERA and a respectable 3.44 fielding-independent pitching rate in forty 1967 appearances. The Mets had a crowded bullpen then, and Shaw was attractive to other teams including the White Sox, though. The Mets wanted Agee in the proverbial worst way possible. For reasons lost to time, Shaw was also one of Grant’s particular pets.

“Gil Hodges wanted him,” Herzog would remember. “Bing, [personnel director] Bob Sheffing, and I all wanted him, and we had the deal set.”

But Bing said we’d have to wait until Grant flew in to approve it.

The deal leaked to the papers, and when Grant hit town, he was furious. “How could you think about trading my Donnie Shaw?” he asked.

And he killed the deal. We eventually got Agee anyway [for Davis, pitchers Jack Fisher and Billy Wynne, and catcher Buddy Booker], but Grant’s decision cost us a good man—Bing Devine. ‘I don’t really believe they need a general manager around here,’ he told me.

And he went back to the Cardinals.

It wasn’t the last time the White Rat dealt with the kind of team lord who meddled without knowledge aforethought. Snubbed by the Mets upon Hodges’ death (they named Hall of Famer Yogi Berra to succeed Hodges, instead), Herzog took his first managing gig with the Rangers for 1973.

Owner Bob Short promised Herzog that high school pitching phenom David Clyde would be allowed to go to the minors for proper further development after two major league starts to goose the hapless Rangers’ home gate. Clyde did pitch well in those first two starts. Then Short reneged on his promise.

“You could have renamed the owner Short Term for the way his mind worked,” Herzog remembered in his memoir, You’re Missin’ a Great Game. When I had the pleasure of interviewing Clyde a few years ago, I asked him whether Herzog was the only man in the Rangers’ organisation who wanted to do right by him.

“As far as I know,” replied Clyde, the lefthander who now fights for pension justice for over 500 pre-1980, short-career major leaguers frozen out of the 1980 pension realignment, “that’s the absolute truth.”

Herzog didn’t survive 1973 in Texas; he was cooked the moment Billy Martin was fired by the Tigers that August and Short could snap him up post haste. The White Rat was brought aboard in Kansas City in 1975, after managing the Angels a year, and he managed the Royals to three straight postseasons in a five-year tenure. In each one, the Yankees thwarted his Royals.

Then he ran afoul of Royals owner, Ewing Kauffman and GM Joe Burke, with whom he’d also tangled in Texas. He despaired of trying to build the kind of bullpen that would help him get past the American League Championship Series, and he despaired equally of trying to convince the Royals brass that he knew what he was talking about when he advised them several key players now had drug issues.

The Royals faced the problem by shooting the messenger. It cost them in nasty headlines and four players (outfielders Willie Mays Aikens, Jerry Martin, and Willie Wilson; pitcher Vida Blue) behind bars after the 1983 season.

Herzog with two of his Gold Glove-winning Royals, second baseman Frank White and outfielder Al Cowens. The Royals rewarded the Rat’s warnings of drug problems on the team with a firing squad and paid an embarrassing price a few years later.

In the interim, Cardinals owner Gussie Busch hired Herzog to manage them. Herzog told Busch bluntly his team needed a near-complete overhaul. So Busch put his money where Herzog’s mouth and mind were and named him the GM in addition to being the field skipper.

Herzog overhauled those Cardinals into three-time pennant winners with a 1982 World Series title in the bargain. He also savoured his relationship with Busch, who gave him free reign to visit any time to talk business. (“Draw me up a Michelob, Chief,” the White Rat often hailed Busch on the phone before his visits, “I’m coming up.”)

He rebuilt the Cardinals into a team suited ideally for old Busch Stadium’s canyon dimensions and pool table playing field, for fast grounders, line drivers, swift runners, defensive acrobats (especially Hall of Fame shortstop Ozzie Smith), and maybe one or two power swingers (a George Hendrick here, a Jack [the Ripper] Clark there) to drive them home. And, for control pitchers who knew how to pitch to the ballpark. Just the way he did in Kansas City.

His pitching management was especially effective with his bullpens. Unlike most managers, Herzog paid attention to what was done in the bullpen as well as on the game mound. He knew what others didn’t: relievers throw voluminously enough getting ready to come in. If he warmed a reliever up without bringing him into the game, he gave the man the rest of the day or night off.

The White Rat (so nicknamed because the Yankees thought his hair resembled that of a former Yankee pitcher with the same nickname, unlikely 1951-52 World Series hero Bob Kuzava) was a marriage of old-school tenacity and newer-school depth, though people often forgot the latter while worshipping the former. He told things the way he saw them, charming many and outraging about as many.

He disliked interleague play and the expanded postseason, believing (correctly) that the former was fraudulent and the latter penalised the best teams even if one of them should end up with the final triumph. He also stood well ahead of the pack when—after the Don Denkinger blown call on the play at first in the bottom of the ninth, Game Six, 1985 World Series—he began calling for postseason instant replay. Denkinger himself came out for replay as well, soon enough. Would Herzog have come out in favour of Robby the Umpbot?

“What they’re fighting about,” he wrote about the Missourians who could still see photos of the fateful play in bars and restaurants for years to follow, “is as old as the game: What’s more important, getting it correct, or following the idea that the ump’s always right, no matter how far his head’s gone up his ass?” (Angel Hernandez, call your office.)

Herzog eventually forgave Denkinger, sort of: at a dinner honouring the 1985 Cardinals, team members were presented new Seiko wristwatches . . . and Herzog himself presented Denkinger one in Braille.

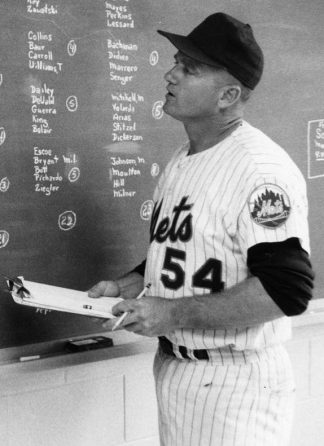

A marginal player on the field, Herzog turned what he learned early from Yankee manager Casey Stengel into a Hall of Fame path that started as a Mets third base coach and, after a year, director of player development.

He didn’t flinch when handed players described most politely as “eccentric”; he embraced them. He treated one and all the same whether praising them or telling them off. He rejected officially what he called the “buddy-buddy” relationship between manager and player(s), but he’d still take a player or three out fishing to help them get their minds clear when struggling for spells.

“I tend to like my players,” he wrote in You’re Missin’ a Great Game. “As long as they knew who was boss, as long as they respected my knowledge of the game when I put the uniform on, I didn’t see any reason not to bring my personality into the situation. It’s one of my resources; why shouldn’t I use it?

“Herzog had only four rules,” wrote Thomas Boswell, when Herzog walked away from the Cardinals in July 1990. “Be on time. Bust your butt. Play smart. And have some laughs while you’re at it.”

Only when those Cardinals stopped half or more of the above did Herzog do the unthinkable. In the same piece, Boswell led with, “They say you can’t fire the whole team, so you have to fire the manager. Nobody told Whitey Herzog.”

On Friday, he fired his team.

Technically, Herzog resigned. But it amounted to the same thing.

The White Rat got sick and tired of watching the St. Louis Cardinals play baseball in a way that offended his sensibilities and injured his enormous pride, so he quit—with a flourish of dignified self-recimination worthy of a disgraced British prime minister.

“I’m totally embarrassed by the way we’ve played. We’ve underachieved. I just can’t get the team to play,” said Herzog. “Anybody can do a better job than me . . . I am the manager and I take full responsibility.”

Translation: They quit on me. So I’m quitting on them. Get me a new team.

Herzog would get a new team when the Angels hired him to examine their farm system up and down. Herzog discovered the Angel system had plenty of good and the parent club needed only a little pitching fortification while letting that good young talent make its way to Anaheim. Then, after winning a power struggle with another Angel exec, Herzog himself took a hike.

“He was the one who gave us a chance to do anything with guys like Tim Salmon and Jim Edmonds and Garret Anderson,” said successor Bill Bavasi. “The attitude before Whitey came in was that those guys weren’t good enough, that we didn’t have any good young players in the system, but Whitey said, ‘Yes you do, leave ’em alone.’ I’ll always be grateful for that and the fact he was willing to share everything he knows.”

When he turned 90, the White Rat talked to St. Louis Post-Dispatch writer Rick Hummel and trained fire at commissioner Rob Manfred’s game-shortening lab experiments. He might have neglected the broadcast commercials that are at the core of baseball’s lengthening games, but he had most of everything else he mentioned right.

He keeps talking about the three-batter rule for [relief] pitchers. Stupid. And then the tenth inning rule [the free cookie on second to open each extra half-inning]. Stupid. Seven-inning doubleheaders. Stupid. None of that is going to shorten the games at all, until we can lower the amount of pitches that they throw.

Baseball has probably had enough prophets without honour to stock an entire organisation. Herzog’s a prophet with honour but it’s almost as though electing him to the Hall of Fame was a way of saying, “Congrats, Rat, now go back to your fishing boats and shut the hell up.”

He’ll enjoy the afterlife of the just in the Elysian Fields, fishing happily when never failing to miss a great game. It’s we remaining on this island earth who’ll miss the White Rat among us, watching our game, fuming over its self-destructions, but still loving its pleasures, its teachings, its remaining tamper-proof fineries.