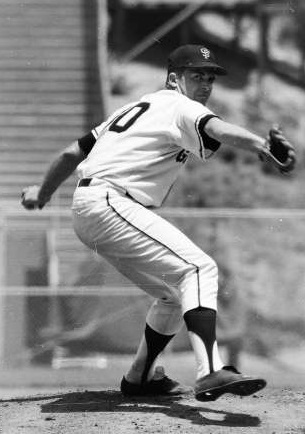

Kevin Gausman isn’t exactly swinging into McCovey Cove here—and he needed a little help from his friend sliding home head first to win Friday night.

Look, I don’t want to be a spoil sport. OK, maybe I do. A little. But anyone getting any ideas about celebrating Giants pitcher Kevin Gausman’s game-winning pinch loft Friday night as evidence against the universal designated hitter . . .

Seriously?

It’s not as though it meant the National League West for the re-tread Giants. They’d already nailed a postseason berth days before. It’s not as though Gausman was the best pinch-hitting option available to manager Gabe Kapler in the bottom of the eleventh with the bases loaded, one out, and relief pitcher Camilo Doval due up.

And, it’s not as though Braves reliever Jacob Webb threw him something with a nasty enough dance to the plate that the biggest boppers in the National League would have had trouble keeping time and step with it.

So come on. Let’s have a little fun with the home crowd in Oracle Park booing the hapless Gausman—who’s actually in the back of this year’s Cy Young Award conversation, having a splendid season on the mound (he woke up this morning with a 2.78 ERA, a 2.88 fielding-independent pitching rate, a 4.2 strikeout-to-walk ratio, and a 10.7 strikeouts-per-nine rate)—because they had no clue Kapler was clean out of position players to send to the plate.

Let’s have a little more fun than that with Webb and Gausman midget-mud-wrestling the count from 1-2 to a full count, because Webb couldn’t find the zone with a search party and a bloodhound and because the Braves handed Evan Longoria and Donovan Solano free passes to load the pads in the first place.

Let’s have a little more fun than that with the Oracle crowd going from lusty booing to standing-O cheering after Webb pumped and delivered a 3-2 meatball that had so much of the zone a real hitter could have turned it into a walk-off grand slam while looking over his shoulder at Brandon Belt in the Giants’ on-deck circle.

But let’s give ourselves a reality check. Gausman’s loft to Braves right fielder Joc Pederson didn’t exactly push Pederson back to the edge of the warning track. It landed in Pederson’s glove while he took a couple of steps forward in more or less shallow positioning.

Shallow enough that the game missed going to the twelfth by about a foot south, on what might have been an inning-ending double play. Except that Brandon Crawford—who’d opened the inning as the free cookie on second and took third on Webb’s wild pickoff throw—had to beat Pederson’s throw home by sliding head first to the plate.

Crawford would have been dead on arrival if he hadn’t taken the dive and traveled beneath Braves catcher Travis d’Arnaud whirling around for the tag that would have gotten the veteran Giants shortstop squarely even if he’d dropped into a standard slide. Even Gausman knows he had a better chance at breaking the land speed record aboard a Segway than there was of him walking it off.

“More than anything,” he said in the middle of his did-I-do-that postgame, “I was trying to not look ridiculous, just take good swings, swing at strikes. Obviously I never would have thought I would have got in that situation coming to the ballpark today.”

Not with a .184/.216/.184 slash line entering Friday night’s follies. Not with a lifetime .036 hitting average entering this season, despite having a reputation as the Giants pitcher with the best bat control at the plate. Not with tending to go the other way when he does connect on those very rare occasions. “Um, well, that’s the first time I’ve pulled a ball,” he said post-game. “Like, in the big leagues.”

Thanks to the rule that says a sacrifice fly doesn’t count as an official at-bat, Gausman’s loft actually cost him four points on his on-base percentage.

The game got to the extras in the first place because, after d’Arnaud himself hit one into the left field seats with two aboard and one out to overthrow a 4-2 Giants lead in the top of the ninth, another Giants pinch-hitter—Solano, hitting for earlier pinch-hitter/outfield insertion Mike Yastrzemski—hit a two-out, 2-2 service from Braves reliever Will Smith only a few feet away from where d’Arnaud’s blast landed.

After not having swung the bat in a major league plate appearance in three weeks, thanks to a turn on the COVID list, Solano at least entered a record book. His game-tyer meant the Giants have hit a franchise-record sixteen pinch-hit bombs this season, and possibly counting.

Gausman, on the other hand, is only the third pitcher in the Giants’ San Francisco era to win a game with a pinch swing. He joins Don Robinson (bases-loaded pinch single, 1990) and Madison Bumgarner (pinch single, 2018) without a base hit for his effort.

The way the Giants have played this year, cobbled together like six parts Clyde Crashcup and half a dozen parts Rube Goldberg, nobody puts anything past them now.

Gausman is respected as one of the nicer guys in the game. Before Friday night’s contest the Bay Area chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America handed him their Bill Rigney Award for cooperation with the Bay Area press. “He’s been terrific, including during some trying times with his family,” said the San Francisco Chronicle‘s Susan Slusser announcing the award presentation.

But he didn’t really do any anti-DH people any real favours after all. He hasn’t augmented any legitimate case for keeping any pitchers swinging the bat any further than this year. The best thing you can say for his Friday night flog is that he connected. He ought to buy Crawford steaks for the rest of the season for sliding astutely.

This year’s pitchers at the plate woke up this morning with a whopping collective .110/.150/.142 slash line and an absolutely jaw-dropping .291 OPS. They’re also leading the league in wasted outs (388 sacrifice bunts), with the next-most-prolific such among the position players being the shortstops. (55.)

Now, for the money shot. Belt is one of the National League’s more consistent hitters this season. He took a .942 OPS into Friday night’s game. He whacked a two-run homer to vaporise a Giants deficit in the first inning. With one out, would any sane manager ask a pitcher to do anything more than stand at the plate like a mannequin, with a bat like that waiting on deck to hit with ducks on the pond?

Kapler’s living the proverbial charmed life. As a player, he was a member of the 2004 Red Sox who finally won their first World Series since the Spanish flu pandemic. He wasn’t exactly one of those Red Sox’s big bats, but he was a late-Game Four insertion as a pinch runner, with then-manager Terry Francona letting him hang around in right field as the Red Sox nailed the Series sweep in the ninth.

As the Dodgers’ director of player development in 2015, Kapler got away with a feeble response at best, when a couple of Dodger minor leaguers were accused plausibly of videotaping an assault by two young women against a third, plus sexual misconduct involving a player’s hand down the victim’s panties. The team elected not to report it to the commissioner’s office or to the police—and he didn’t go over their heads to do so, either.

Then, Kapler was run off the Phillies bridge because, in two seasons, he couldn’t marry his analytical bent to the live situations in front of him and the Phillies ended up three games under .500 total with him on their bridge.

Now, he has the bridge of the National League West leaders fighting tooth, fang, claw, and charm against those pesky Dodgers with a two-game division lead and fourteen games left. He’d better not get too comfortable emptying his bench again any time soon. His pitchers are only hitting .081 this season. And they won’t always have Crawford on third to bail them out in a pinch.

At long enough last came Opening Day. Well, Opening Night. On which New York Yankees right fielder Aaron Judge nailed the COVID-19 delayed season’s first hit and his teammate Giancarlo Stanton nailed its first home run two batters later.

At long enough last came Opening Day. Well, Opening Night. On which New York Yankees right fielder Aaron Judge nailed the COVID-19 delayed season’s first hit and his teammate Giancarlo Stanton nailed its first home run two batters later.