Kershaw gets to retire as few of the greats truly do—on his own terms.

Often as not, you learn more about those whose careers you admire by the way they face the end than by the ways they did what earned your admiration. In Clayton Kershaw’s case, it might not be learning but re-learning.

When Kershaw froze the Giants’ Rafael Devers like ice cream with a strike-three fastball that could have been accused of clogging up the passing lane to open the top of the fifth Friday night, his mates in the infield surrounded and hugged him, then he handed the ball to Dodgers manager Dave Roberts. Roberts’s final season as a player was Kershaw’s first.

Now, Roberts put an arm around Kershaw and congratulated him on the career that’s written his likely first-ballot Hall of Fame ticket. Kershaw had only one reply: “I’m sorry I pitched so poorly tonight.”

Then, the 37-year-old lefthander looked toward his wife and four and a half children (Mrs. Kershaw is expecting their fifth) in the stands and motioned to the Dodger Stadium crowd before walking down from the mound and toward the dugout. He gave the crowd the curtain call they all but demanded, knowing they’d seen him pitch at home for the final time, then disappeared.

“I’m kind of mentally exhausted today, honestly,” he said after the Dodgers finished the game with a 6-3 win, “but it’s the best feeling in the world now. We got a win, we clinched a playoff berth, I got to stand on that mound one last time. I just can’t be more grateful.” Note the order in which he listed all of it. We first, I second.

That attitude enabled Kershaw not just to rule the earth from the mound in his prime but to pick up, dust off, start all over again after more mound heartbreak than the all-time greats should be allowed. When he triumphed, it was splendor on the mound; when he didn’t, it was down at the end of Lonely Street to Heartbreak Hotel. Never once did Kershaw take the triumphs for granted or the heartbreaks for finalities.

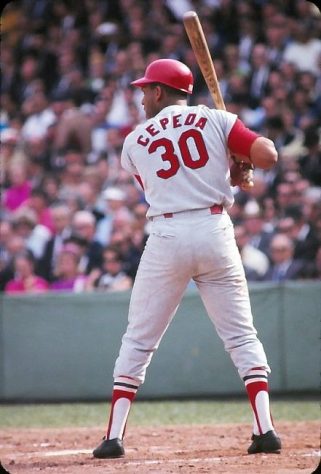

Kershaw beginning to deliver the strike three freezer to the Giants’ Rafael Devers, his final regular season batter and strikeout in Dodger Stadium.

No worse hour befell him, perhaps, than the night the Nationals yanked the Dodgers out of the 2019 postseason. The division series night Roberts sent Kershaw in relief of Walker Buehler and Kershaw yanked the Dodgers out of a seventh-inning Game Five jam by striking Adam Eaton out on three pitches. The night Roberts should have met Kershaw en route the dugout, given him the proverbial pat on the posterior, then taken the ball and brought Kenta Maeda in for the eighth to do what the manager later admitted thinking should have been done originally: face Anthony Rendon and Juan Soto.

Oops. Kershaw went out for the eighth. He threw Rendon a 1-0 fastball that looked as though it might catch the corner. Looks were so deceiving that Rendon sent it over the left field fence. The next pitch Kershaw threw, to Soto, was a slider that hung just enough for Soto to hang it into the right field bleachers. Then Roberts brought Maeda in. And Maeda struck the next three Nats out in order.

Those blows tied the game at three each, but Kershaw wasn’t anywhere near the mound when Howie Kendrick wrecked Joe Kelly and the Dodgers with the grand slam that punched the Nats’ tickets to the National League Championship Series. (And, to their eventual World Series conquest.) Some small packs of Dodger fans relieved themselves by running their cars over Kershaw jerseys in the postgame parking lot anyway.

Kershaw couldn’t bring himself to say what had to be said, that his manager inexplicably set him up to fail. Instead, he took the responsibility for himself.

“That’s the hardest part every year,” Kershaw said postgame. “When you don’t win the last game of the season and you’re to blame, it’s not fun . . . Everything people say is true right now about the postseason. I understand that. Nothing I can do about it right now. It’s a terrible feeling, it really is.”

He’d go forth to claim two World Series rings, in 2020 and 2024, even though his fractured toe kept him from pitching in last October other than cheerleading. His career 154 ERA+ leads all still-active pitchers. His 2.85 lifetime fielding-independent pitching rate is second among the active only to the often ill-fated Jacob deGrom. His resumé includes three Cy Young Awards, a Most Valuable Player award, and a no-hitter. Baseball-Reference considers Kershaw the number 20 starting pitcher who ever hit the mound; he was the best starting pitcher of his own time before his body finally started telling him, “That’s what you think.”

The fastball isn’t Little Johnny Jet anymore. The curve ball Vin Scully himself labeled Public Enemy Number One might be headed for Leavenworth. The slider that really turned Kershaw from good to great to extraterrestrial has lost just enough of its slide. But he is still Clayton Kershaw, and he will still have a role in the Dodgers postseason. Even if it’s coming out of the bullpen. He’ll be valued, even if he’ll let other arms hog the headlines for better or worse.

He didn’t pitch as poorly as he thought he did Friday night. Sure, he surrended a pair of earned runs and walked four while scattering four hits otherwise, but he struck six out in his 4.1 innings’ work. Even if that freezer to Devers looked borderline enough that you could wonder whether plate umpire Lance Barksdale might have let the moment and the legacy inform his judgment.

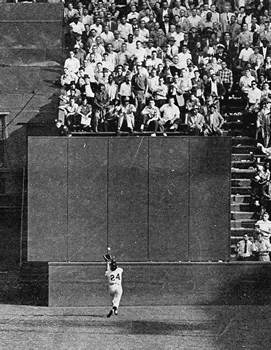

L to R—Cooper, Charley, Chance, Ellen, and Cali Kershaw contribute to the ovation for their future Hall of Famer as he’s about to begin his final regular-season Dodger Stadium start.

The night before, Kershaw made his pending retirement official, after an annual flirtation with the idea. True to form, he was humble and appreciative, right down to letting his wife share the moment by way of reading a letter she wrote him for the occasion:

From my perch, I have been uncomfortably pregnant, nursed newborns, rocked them to sleep to the roar of the seventh-inning stretch to get their last nap in. Fed them baby food, pouches, teething with crackers, changing blowout diapers, been frazzled with toddlers, tantrums and meltdowns, chased them through the concourses. A Mary Poppins bag filled with tricks and games to keep them occupied, and ironically teaching them the ins and outs of baseball. Explaining all the numbers on the scoreboard and the concession line, the ballpark food.

(I’ve) cried over some really hard losses and some really incredible milestones. (I’ve) watched our kids fall in love with the game, with the players and watching you pitch. Singing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” chasing beach balls, ducking from fly balls, spilling food and popcorn all over the fans below them. (I’ve) done it thousands of times, thousands of bathroom runs, all in the stadium. The workers and ushers are (our) best friends now.

A tear crept down Kershaw’s cheek as he read it.

“I’m really not sad. I’m really not,” he said later in the conference. “I’m really at peace with this. It’s just emotional.”

Few of the greats get to choose their own retirement terms. But they show more of what they’re made of when they do so than they ever showed on the field. Kershaw facing the end, whenever it may prove to be, showed more than any triumph and transcended any tribulation. No wonder grown adults wept for and with him.