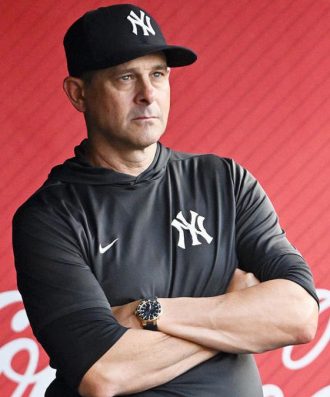

Aaron Boone—how often does a four-game division lead feel like the next rung down of a collapse?

“If we don’t dig ourselves out,” Yankee manager Aaron Boone told reporters after the Yankees lost to the Rays 2-1 Saturday night, “you’ll have a great story to write.” Sometimes, greatness is in the eye of the beholder. If the beholder is a typical Yankee fan, this kind of greatness is the last thing the Yankees need.

There’s always been a trunk full of cliches about the Yankees. The two most significant have been a) they don’t like to lose; and, b) their fans consider no postseason legitimate unless the Yankees are in it. (The third most significant, at least since a certain man bought the team in 1973: To err is human; to forgive is not Yankee policy.)

Even the terminally optimistic Boone feels the weight. If he’s telling reporters they’ll have a “great” story to write unless the Yankees find a way out of their current spinout, there’s no joy in half of New York. The other half is hanging with the Mets, who may have a mere two-game lead in the National League East but whose fans aren’t exactly ready to call for summary executions despite their team having ended May 10.5 games ahead of their divisional pack.

The Mets’ faithful learned from the crib that there’s no such thing as an entitlement to success. (Quick: Name any Yankee team ever called a miracle team.) The Yankee faithful were spoiled so rotten by their 20th Century success that their descendants still think the World Series trophy is fraudulent unless it has the Yankee name on it.

Maybe the Yankees will dig themselves out of their present funk. But maybe they won’t. They’re 15-16 in the second half so far and went 10-18 in August alone, but they awoke Sunday morning having lost six of nine. Dropping the first pair of a weekend set with the second-place Rays is one thing, but entering that set splitting four with the sad-sack Athletics and two of three to the equally sad-sack Angels is not the look the Yankees wanted going in.

Their toughest opponents the rest of the way will be those same Rays for a three-game set in Yankee Stadium starting 9 September. They return home from Tampa Bay to host the Twins for four, and the Twins are no pushovers, but they’re not exactly up to the Rays’ performance level just yet. They’re also not quite up to the level of the suddenly-amazing Orioles, whom the Yankees host to end September and open October.

The Orioles—who looked as though they’d surrendered their heart and soul when trading Trey Mancini at the trade deadline, which could have threatened their unlikely sightline to the wild card picture. While almost nobody was looking, the Orioles not only finished July with a 16-9 month but they consummated a 17-10 August and opened September with three straight wins—one against the AL Central-leading Guardians and two against the A’s. Once upon a time the victims of a miracle team (in 1969), these Orioles may yet <em>become</em> a miracle team themselves.

They were as deep as 23 games in the AL East hole as of 2 July. They were 35-44. They’ve since gone 36-25. This regular season may yet finish with a debate over which was greater, the Yankees’ collapse from a one-time 15.5 game AL East lead or the Orioles’ resurrection from a 23-game divisional deficit to a postseason berth.

Yankee and other eyes concurrently train upon Aaron Judge’s pursuit of the 60 home run barrier across which two Yankees have gone (Hall of Famer Babe Ruth’s 60 in 1927; Roger Maris’s 61 in ’61) and—after a healthy leadoff belt in the top of the ninth off Rays reliever Jason Adam Saturday night—Judge himself is only eight shy of meeting. Some think Judge is so locked in he may even meet the 70-bomb single-season barrier head-on before the regular season expires. He’d be the first player to reach it without being under suspicion of actual/alleged performance-enhancing substances, anyway.

But Yankee cynics make note that, for thirty days including Saturday night, the Yankees’ team slash line of .213/.289/.325 is only that high with Judge, himself the possessor of a .279/.446/.593 slash for the same span. Without him, they’d be .208/.268./.295. Their Lost Decade of 1965-75 looked better than that.

How on earth did the Yankees get here? Easy enough. Hal Steinbrenner isn’t the man his father was, good and bad. The good side: Prince Hal isn’t exactly the type to decide one bad inning is enough to demand heads on plates, and if he fires a manager he wouldn’t have the gall to say, “I didn’t fire him. The players did.” The bad side: He doesn’t like to invest half as much as his father did.

Say what you will about George Steinbrenner, but the man didn’t care how much he had to spend, either on the free agency market or on keeping the farm reasonably fresh. Prince Hal’s running the most profitable franchise in the American League as if they were a minor league outlier or the A’s, whichever comes first. Nobody wants the bad side of The Boss resurrected, no matter how often Yankee fans demand it now. But nobody wants the good side buried interminably, either.

Which means general manager Brian Cashman, the longest-tenured man in his job in baseball, had little choice but to cobble a roster with one proverbial hand tied behind his back. But that acknowledgement goes only so far. Cashman’s eye for diamonds in the rough has failed him long enough. The present Yankee roster makes some rebuilding teams (the Orioles, anyone?) resemble threshing machines.

Which also means Boone—the only man in Yankee history to manage back-to-back 100-game winners in his first two seasons on the bridge—looks a lot larger for his faltering in-game urgency managing and getting less than the best of the men not named Judge or (relief pitcher) Clay Holmes on his roster. So do the three Yankee hitting coaches who can’t seem to shake the non-Judge bats out of what one of them is quoted as calling the wrong case of the “[fornicate]-its.”

The definition to which those coaches hold is translated admirably by strongman designated hitter Giancarlo Stanton: “We’ve just got to give whoever is on the mound a tough at-bat, even if we get out. We’ve just gotta wear ’em down a little bit. Just be a little tougher on them.” The definition to which the Yankee bats have held mostly of late seems to be unintentional surrender.

Yes, the Yankees have been injury-addled. Yes, they’ve been playing a curious chess game with minor leaguers brought up to the club to the point where they had to send two promising pitchers back down because the roster was about as flexible as an iron gate. But the lack of urgency the Yankees seemed to feel when they looked like AL East runaways hasn’t been resolved just yet with the team looking as though they can be overtaken before this is over.

Once upon a time, New York was rocked by a Brooklyn Dodgers team that looked as though it was shooting the lights out in the National League but found itself overtaken into a pennant tie by a New York Giants team that was 13 games out at one point. That tie and subsequent playoff, of course, turned out to be as tainted as the day was long. (The Giants stole the pennant! The Giants stole the pennant!)

To the best of anyone’s knowledge, nobody’s cheated their way back into the AL East race. If the Yankees keep up their current malaise, nobody would have to. Collapsing entirely from a 15.5 game lead would stand very much alone on the roll of Yankee infamy.