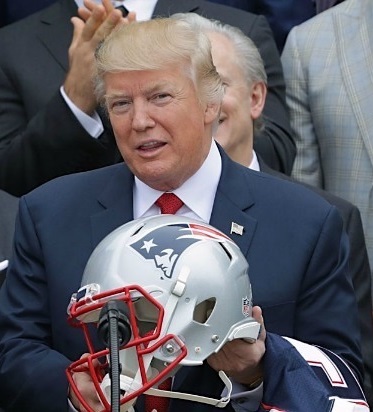

President Donald Trump, holding a New England Patriots helmet at the White House celebrating the Pats’ Super Bowl LIII victory. He managed to conflate a football beneficiary of the former Alabama coach running for the Senate with the man who coached the Pats’ American Football League ancestors, among others.

When last we had occasion to think of Donald Trump in sports terms having nothing to do with kneeling during the National Anthem, he attended Game Five of the last World Series in Nationals Park. He was booed rather lustily, with intermittent chants of “Lock him up!” punctuating the chorus.

The “lock him up!” chants returned in the seventh inning—not for President Tweety, but for home plate umpire Lance Barksdale, whose evening to that point was full of such dubious calls (including the fourth ball called a third strike on Nationals outfielder Victor Robles during the inning) that both Nationals and Houston Astros fans alike wanted him in the stockade.

Now, though, the president about whom “polarising” often feels high praise arouses the attention of Deadspin, the online sports publication. He arouses it by way of the campaign trail, on a conference call, supporting former longtime Auburn University football coach Tommy Tuberville’s campaign as Alabama’s newly-crowned Republican nominee to the U.S. Senate.

Trump wanted to praise Tuberville as the reason the University of Alabama hired a particular football coach, after the Auburn Tigers bushwhacked the Crimson Tide in six straight meetings between the two schools. Then, he wanted to praise that coach. Uh, oh. “Beat Alabama, like six in a row, but we won’t even mention that,” President Tweety began, starting with Tuberville. “As he said . . . because of that, maybe we got ‘em Lou Saban . . . And he’s great, Lou Saban, what a great job he’s done.”

Crimson Tide coach Nick Saban must be double-checking his records to be sure he didn’t change his name inadvertently, somewhere. And, to re-assure himself, with apologies to Mark Twain, that the reports of his death have indeed been exaggerated greatly. The National Football League and its long-ago-absorbed upstart competitor the American Football League would love to know how the real Lou Saban coached from beyond.

That real Lou Saban, as Deadspin couldn’t wait to remind anyone caring, coached in both American pro football leagues and in college football for a very long time. But not past 2002, after a decade of working at far lower than Division I programs.

The president who once denounced the late Sen. John McCain for having been captured as a prisoner of war during the Vietnam War (“I like people who weren’t captured”) and makes a fetish of “winning” (without stopping to think that one man’s “winning” is another’s self-immolation) chose quite a winner to conflate with Alabama’s incumbent football coach.

Saban, who may or may not be a second or more distant cousin to Nick, was a charter coach of the Boston Patriots, when the AFL was born in 1960. From there he enjoyed a sixteen-season career coaching in the AFL and—when his Denver Broncos moved with the merger—the NFL. He had three first-place finishes (coaching the Buffalo Bills, 1963-65) and two AFL championships. And that’s all, folks.

He had six winning seasons in sixteen coaching the pros. His final record as a pro football coach is 95-99-7. Except for his back-to-back AFL championships, Saban never led his teams past a single playoff win. He did get to return to the Bills in 1972, coaching the teams fabled for O.J. Simpson and the Electric Company offensive line, but they never got past second place or a single playoff loss, either. He resigned after a 2-3 start in 1976 and never coached in the NFL again.

But he did return to the college coaching lines, which he’d visited once in the middle of his pro coaching life (University of Maryland: 4-6 in 1966), and where his coaching career began for a single season in 1956. (Northwestern University: 0-8.) He coached the University of Miami to back-to-back losing seasons (1977-78) and Army (1979) to one losing season. His complete coaching record at the major schools: 15-35-2.

Saban left Miami in the middle of a row over three freshman players attacking a Jewish student in yarmulke while he walked toward a campus religious service. They carried him to Lake Osceola in the middle of the campus and threw him in. Having been off campus when the attack happened, Saban returned to learn of it and say, according to Bruce Feldman’s history of Miami football, “Getting thrown in the lake? Sounds like fun to me.”

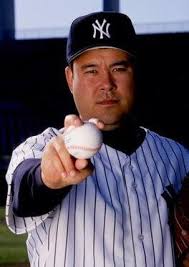

After he left Army, Saban took a brief, curious career turn. He became one of George Steinbrenner’s “baseball people,” doing Steinbrenner (a personal friend) a favour and becoming president of the New York Yankees for 1981-82. Even allowing that Steinbrenner did love football, engaging a football lifer as a baseball president seemed along the line of hiring a furniture designer to develop vacuum cleaners.

If Saban had anything to say about some of the turmoil around those Yankees, there seems little enough record of it:

* Steinbrenner fired first-time manager Gene Michael in 1981, after Michael challenged The Boss to knock it off with the constant threats. Steinbrenner’s bid to mollify The Stick became a classic of Yankee panky: Why would you want to stay manager and be second-guessed by me when you can come up into the front office and be one of the second guessers?

* Steinbrenner burned through three managers in 1982: Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Lemon (who’d picked up Billy Martin’s pieces and led the Yankees to a World Series championship in 1978), Michael again, then Clyde King.

* Steinbrenner hired former Olympic hurdler Harrison Dilliard to help turn the Yankees into a speed team, an idea so hilarious as it was accompanied by continuous running drills in spring training that wags began calling the Yankees “the Bronx Burners.” (The experiment lived only slightly longer than some Yankee managers kept their jobs.)

The man who thought it sounded like fun for three of his Miami players to dunk a Jewish student in Lake Osceloa isn’t on record anywhere that I know of suggesting what fun Steinbrenner’s King of Hearts act in the south Bronx must have been for those on the wrong end of His Majesty’s scepter.

Lou Saban died at 87 in 2009, two years after Alabama hired Nick. He might not have had a real reputation as a long-term winner but he did have one as a teacher. He was also in no position to be the direct beneficiary of Tuberville’s constant seawalling of the Crimson Tide. Alabama isn’t exactly renowned for hiring octogenarian head coaches. Nick Saban, on the other hand, has a long-term winning reputation in college football: a 248-65 record; three Bowl Championship Series wins; and, ten bowl game wins otherwise.

Deadspin offers the charitable suggestion that Trump might have conflated Saban with Lou Holtz, the Notre Dame coaching legend. Careful with that axe, Eugene: In some portions of the South, confusing or conflating a Crimson Tide coach with some Hoosier coach can provoke the same kind of tavern debate (if not brawl) as could be provoked in the northeast, formerly, if you inadvertently confused or conflated Mookie Betts with Mookie Wilson.

Trump’s sports record is dubious at best, shall we say. When he hasn’t beaten his gums about kneeling National Anthem protesters (a subject for another time, for now), he’s been a football owner (in the failed United States Football League some say he destroyed in the first place), a less-than-knowledgeable advocate (speaking politely) of Pete Rose’s reinstatement to baseball and election to the Hall of Fame, and a public critic, equally less than knowledgeable, of Maximum Security’s rightful disqualification in the 2019 Kentucky Derby.

With an expert like that on his side, I’m not entirely sure that Tuberville—whose own college football coaching career was impressive enough (159-99 record; seven bowl wins)—needs adversaries.