Nothing got past The Hoover too often in two decades at third base.

When Hall of Fame third baseman Brooks Robinson celebrated his 83rd birthday, I couldn’t resist having a little mad fun with his nickname, actual or reputed. Commonly known as the Human Vacuum Cleaner, I recalled longtime Washington Post writer Thomas Boswell calling him The Hoover.

Considering how he beat, swept, and cleaned at third base for two decades, I thought Boswell had it more dead on. So did Reds first baseman Lee May during the 1970 World Series. May first called Robinson—who died at 86 on Tuesday—the Human Vacuum Cleaner at that time. Then, May asked, right away, “Where do they plug Mr. Hoover in?”

Anyway, I thought of other great fielders at third and otherwise. Almost none of them were quite on Robinson’s plane. (“I’m beginning to see Brooks in my sleep,” lamented Reds manager Sparky Anderson during that Series. “I’m afraid if I drop this paper plate, he’ll pick it up on one hop and throw me out at first.”) But they were some of the best their positions ever hosted.

Fellow Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt combined breathtaking power at the plate with his own kind of sweeping and cleaning at third. Considering that plus his sculpted physique, I thought that, for him, it could only be the classic Electrolux, the sleek tank vacuums of 1924-2004.

You couldn’t possibly top The Wizard of Oz for Ozzie Smith at shortstop, but I tried. For him, I designated Aero-Dyne, the model name of Hoover’s first tank-style vacuum cleaner. Nor could you possibly top Graig Nettles’s actual nickname, Puff the Magic Dragon, and I was kind enough not to try. But for others, I came up with things like these:

The Constellation—Roberto Clemente. Hoover’s once-famous, Saturn-shaped canister, born as a swivel-top in 1951, seems to fit Clemente since it often seemed that his ways of running balls down and cutting baserunners down did emanate from somewhere beyond this galaxy.

The Courier—Andruw Jones. That machine was Sunbeam’s brilliant 1966 idea of stuffing vacuum cleaner works into what resembled a Samsonite hard-shell suitcase. Jones traveled so many routes so well becoming baseball’s all-time run-preventive center fielder that you could only think of him as the Courier delivering messages of doom to opposition swingers and runners.

The ElectrikBroom—Keith Hernandez. Mex was as sculpted at first as Schmidt was at third. As vacuum cleaners went, the classic Regina ElectrikBroom was the Bounty paper towel of its time: the quicker picker upper. That was Hernandez at first base.

Eureka—Ken Griffey, Jr. Tell me you saw him turn center field into his personal playground and making spectacular catches without thinking, “Eureka!”

The Hoover Junior—Mark Belanger. Robinson’s longtime partner at shortstop and the second most run-preventive player at his position ever behind The Wiz. The only reason he won’t be in the Hall of Fame is because he couldn’t hit if you held his family for ransom.

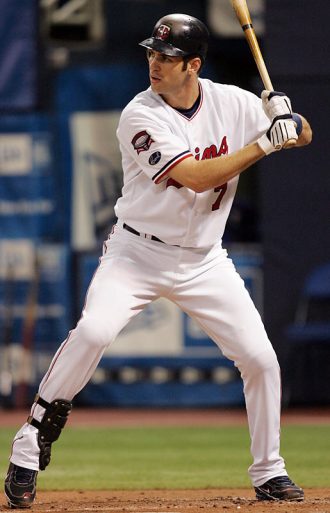

The Kirby—Kirby Puckett. Should be bloody obvious.

The Premier—Johnny Bench. Should be self explanatory if you saw him behind the plate. (After watching Robinson’s third base mastery against his team in that 1970 Series, Bench quipped of his MVP award, “If he wanted the [MVP prize] car that badly, we’d have given it to him.”)

The Roto-Matic—Clete Boyer. That Yankee third base acrobat moved around so much cutting balls off at the third base pass you could have mistaken him for the swiveling hose atop Eureka’s canister cleaner of the same name.

The Royal—Curt Flood. The king of defensive center fielders when Mays began to show his age. (Maybe it should have been a wet-dry vac, since it was said so often that three-quarters of the earth is covered with water and the rest was covered by Flood.)

The Swivel-Top—Willie Mays. That General Electric canister of the early 1950s boasted of giving you “reach-easy” cleaning, and Mays was nothing if not the reach-easy center fielder of his time.

There was more to Robinson, of course, than just his third base hoovering. There was the decency that enabled this white son of Little Rock, Arkansas, to welcome African-American son of Oakland, California by way of Beaumont, Texas Frank Robinson, upon the latter’s controversial trade out of Cincinnati after the 1965 season. “Frank,” Brooks said, “you’re exactly what we need.”

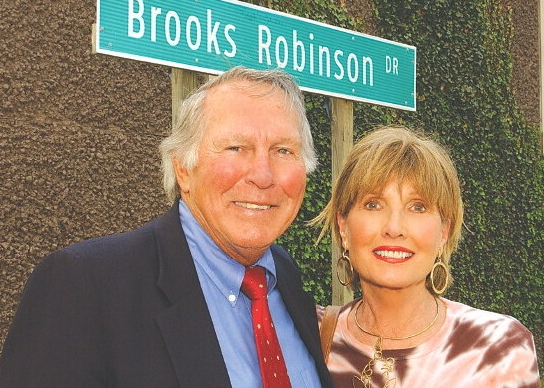

Brooks Robinson and his wife, Connie, at the dedication of Brooks Robinson Dr. in Pikesville, Maryland, just off the Baltimore Beltway, in 2007. The Hoover and the stewardess whose feet he swept her off aboard a 1959 flight to Boston were married 63 years.

There were the eighteen All-Star Games, the sixteen straight Gold Gloves, the 1964 American League Most Valuable Player award, the 1970 World Series MVP. (Forgotten amidst the beating, sweeping, and cleaning at third base that Series: The Hoover hit a whopping .429 with his plate demolition including two home runs.)

There were the 39.1 defensive wins above replacement level (WAR) and the 105 OPS+, making Robinson one of only two players ever to have 30+ dWAR and an OPS+ over 100. The other? Fellow Hall of Famer Cal Ripken, Jr.

There was the end of his career, the final two seasons when the Orioles essentially carried him despite his diminution at the plate and his age-reduced range at third—simply because a) they thought so well of him as a man, and b) they knew he needed the money. Bad. And he wouldn’t in position to benefit from the advent of free agency.

He was broke and in debt thanks to his off-season sporting goods business. Not because he made mistakes but because he was taken advantage of. “At every turn,” Boswell wrote (in The Heart of the Order), “Robinson’s flaw had been an excess of generosity.”

How could he send a sporting goods bill to a Little League team that was long overdue in paying for its gloves? He’d keep anybody on the cuff forever. Said Robinson’s old friend Ron Hansen [one-time Orioles middle infielder], “He just couldn’t say no.” As creditors dunned him and massive publicity exposed his plight, Robinson answered every question, took all the blame (including plenty that wasn’t his), and refused to declare bankruptcy. He was determined to pay back every cent. With great embarrassment, he returned tens of thousands of dollars that fans spontaneously sent him in the mail to soften his fall.

When the Orioles gave him a Thanks Brooks Day upon his 1977 retirement, the master of ceremonies was Associated Press writer Gordon Beard. “Around here,” he said, “people don’t name candy bars after Brooks Robinson. They name their children after him.”

This was the fellow who’d autograph anything proffered—including, it’s been said, a pet rock and a bra. A fellow who so appreciated what he was able to do for a living for his first two decades of adulthood that, when the end came nigh, he could only be grateful for having been there at all.

“Every player I’ve ever managed,” cantankerous Orioles manager Earl Weaver told Boswell, “blamed me at the end, not himself. They all ripped me and said they weren’t washed up. All except Brooks. He never said one word and he had more clout in Baltimore than all of them. He never did anything except with class. He made the end easier for everybody.”

Robinson in retirement climbed out of his financial hole well enough, becoming a popular localised Orioles broadcaster in the 1980s with a flair for candid and perceptive analysis even when it meant being critical. If he lacked anything in those years, it was ambition. He never sought to manage in baseball and he never sought a national audience on the air, but he did have partial ownership of a pair of minor league teams for a time.

The Orioles have retired only six uniform numbers and one is Robinson’s number 5. His statue looms inside Camden Yards, where the Orioles and the Nationals observed a moment of silence before Tuesday night’s game, lined up outside their dugouts, in respect. The American League East-leading Orioles beat the Nats, 1-0.

Robinson also served as chairman of the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association’s board of directors. If there’s any single blemish on his resumé, it’s that he didn’t move the group toward helping to gain redress for pre-1980 short-career players frozen out of the 1980 pension re-alignment. “He dropped the ball, says A Bitter Cup of Coffee author Douglas Gladstone. “He never went to bat for them, many of whom were his teammates.”

In recent years, the first-ballot Hall of Famer dealt with health issues such as prostate cancer (he 32 radiation treatments), a subsequent followup surgery, and a fall that hospitalised him with a shoulder fracture in 2012. He also became an Orioles special advisor, insisting that it be tied to community events. He was quoted as telling owner John Angelos he’d do anything except make baseball decisions: “That’s passed me by, if you want to know the truth.”

The only love deeper than baseball in Robinson’s life was his wife, Connie, whom he met in 1959 aboard an Orioles flight to Boston when she was a stewardess on board. (They married in 1960.) When he auctioned off his volume of remaining memorabilia (My children, they have everything they ever wanted from my collection), the proceeds went to a foundation the couple established for worthy Baltimore causes, a Baltimore adopted son to the end.

Now The Hoover will beat, sweep, and clean the Elysian Fields. He might even pick up a paper plate and throw Sparky Anderson out at first.