Willie Mays played with Gary Mathews.. Who played with Edgar Martinez.. Who played with Ichiro.. Who played with Tim Beckham.. Who played with Blake Snell.. Who played with Heliot Ramos.. Who homered tonight while playing CF for the Giants… In Willie Mays’ first pro ballpark. Baseball!—Jayson Stark, Hall of Fame baseball writer.

In the first professional baseball park where the late Hall of Famer Willie Mays played as a Birmingham Black Baron, it was illegal until 1963 for white and non-white players to play on the same field. On Thursday, white and non-white players converged for the San Francisco Giants and the St. Louis Cardinals to play an official major league game.

None but the blind or the bigoted pretends racism is eliminated from American life entirely. But the Giants and the Cardinals, playing a game umpired by the Show’s first all-black umpiring crew, managed to keep it outside the gates of a ballpark where Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson played on the first interracial team Rickwood Field hosted.

That was then: Jackson’s parent club, the then-Kansas City Athletics, moved its AA-level minor league team into Birmingham at the insistence of its owner, Charles Finley, a Birmingham native who could be flagrantly wrong about many things but stood on the side of the angels when it came to racism. Jackson remembers only too well.

“I walked into restaurants and they would point at me and say, ‘The n—–s can’t eat here’,” Jackson said aboard the Fox Sports pre-game broadcast.

I would go to a hotel and they’d say, “the n—–s can’t stay here.” We went to Charlie Finley’s country club for a welcome home dinner and they pointed me out with the N-word, “he can’t come in here.” Finley marched the whole team out . . . Finally, they let me in there and he said, ‘We’re going to go eat hamburgers. We’ll go where we’re wanted.’

Coming back here is not easy. The racism when I played here, the difficulty of going through different places where we traveled—fortunately, I had a manager and I had players on the team that helped me through it—but I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.

This is now: The Negro Leagues are recognised formally (and appropriately) as having been major leagues. This year, the known statistics of Negro Leagues players and managers (surely there will be more to exhume, however long it might take) began becoming integrated into major league statistics at last.

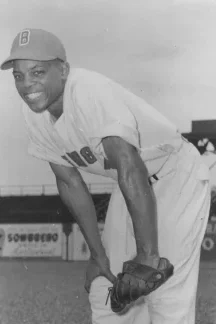

The Rev. Bill Greason, former Birmingham Black Baron who got to pitch very briefly for the Cardinals in 1954.

Thursday evening, the oldest former Negro Leagues player, pitcher turned minister Bill Greason (99), was escorted to halfway between the mound and the plate by Cardinals coach and former player (and the National League’s 1985 Most Valuable Player) Willie McGee to throw a ceremonial first pitch. To Ron Teasley, Jr., whose father is the second-oldest living former Negro Leaguer.

Greason was six years Willie Mays’s senior when they were Black Barons teammates. “He was a determined young man,” the former pitcher told Ken Rosenthal. “He had the gifts, the talent, and he was sensitive to listening to those who were older than he was. It was a tremendous blessing, and we turned out to be real close. Like brothers.” Just the way Mays would look toward former Newark Eagles star Monte Irvin when Irvin was a third-year Giant and Mays a nervous Giants rookie.

Mays’s number 24 was painted in large white numerals behind the plate. A Giants uniform with his number hung in the Giants’ dugout. The Giants and the Cardinals—wearing the uniforms of, respectively, the San Francisco Sea Lions (West Coast Negro Baseball League, 1946) and the St. Louis Stars (Negro National League, 1920-1931)—wore circular patches on their jerseys with Mays’s surname and number.

Mays’s son, Michael, urged the Rickwood crowd to make some noise for his father before the game. “Birmingham, I’ve been telling y’all,” the younger Mays said, “if there was any way on Earth my father could be here, he would. Well, he’s found another way . . . Let him hear you, he’s listening. Make all the noise you can.” The Wil-lie! Wil-lie! chant just about drowned every other sound out.

Mays had issued a statement Monday saying his health would keep him from attending the game. The following day, he died at 93. America couldn’t decide whether to grieve over yielding Mays to the Elysian Fields or be grateful that he remained among us as long as he did.

“In a sense, Mays was too good for his own good,” wrote George F. Will in tribute.

His athleticism and ebullience—e.g., playing stickball with children in Harlem streets–encouraged the perception of him as man-child effortlessly matched against grown men. He was called a “natural.” Oh? Extraordinary hand-eye coordination is a gift. There is, however, nothing natural about consistently making solid contact with a round bat on a round ball that is moving vertically, and horizontally, and 95 mph. Because Mays made the extraordinary seem routine, his craftsmanship and intelligence were underrated.

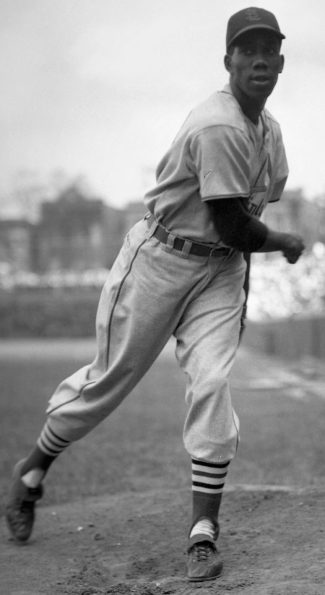

The late Willie Mays, as a young Birmingham Black Baron. (Photo: Birmingham Public Library.)

The arguable greatest position player ever to play major league baseball may have been watching and listening from his Elysian Fields roost on Thursday, but he surely lamented his Giants losing by one run to the Cardinals. Not for lack of trying.

The Athletic‘s irrepressible Hall of Fame writer Jayson Stark couldn’t resist pointing out: “Willie Mays played with Gary Mathews.. Who played with Edgar Martinez.. Who played with Ichiro.. Who played with Tim Beckham.. Who played with Blake Snell.. Who played with Heliot Ramos.. Who homered tonight while playing CF for the Giants… In Willie Mays’ first pro ballpark. Baseball!”

That would be Ramos tying the game at three-all when he took hold of a two-on, one-out, one-strike service from Cardinals starting pitcher Andre Pallante and launched it the other way, over the painted Budweiser ad on the right field fence.

The Cardinals kind of snuck back into the lead an inning later on a sacrifice fly (Nolan Gorman) and a run-scoring (Alec Burleson) wild pitch (from Giants reliever Randy Rodriguez), and padded it to 6-3 in the bottom of the fifth when Brendan Donovan sent home his third run of the game, singling up the pipe to score Burleson. The Giants got two back in the top of the sixth on an RBI single (Wilmer Flores) and a sacrifice fly (Nick Ahmed), but that was the end of the game’s scoring.

The all-black umpiring crew even managed to behave, from Alan Porter behind the plate onward. Perhaps wisely, they confined the otherwise dubious C.B. Bucknor to second base, where he couldn’t possibly commit half the mischief he normally does when he’s assigned to call balls and strikes.

For one evening Rickwood Field became the Show’s oldest park in which to play a game; built originally in 1910, it’s two years older than Fenway Park and four older than Wrigley Field. It also became the place where racism’s ghosts were made unwelcome, even as few, perhaps, beyond the assembled former Negro Leaguers, might have guessed whom its most troublesome ghost might have been.

The once all-white minor league Birmingham Barons, to whose games Mays listened as a youth, had a radio play-by-play announcer from 1932-1936 named Bull Connor, who just so happened to be Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety at the same time. “Pretty good announcer, too,” Mays once remembered of him, “although I think he used to get excited.”

That pretty good announcer eventually ordered fire hoses and attack dogs turned upon student civil rights demonstrators, in 1963, the horror of which helped speed the writing, passage, and acceptance of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Connor is long gone. So is the legal framework by which Jim Crow wreaked his infamy. But only that.

There remain miles to go yet before racism’s cancer is eradicated entirely from too many hearts and minds, still, who might have remained oblivious Thursday night to what its absence can achieve, even on a baseball team. Thursday was one more round of chemo, but an instructive and endearing one.