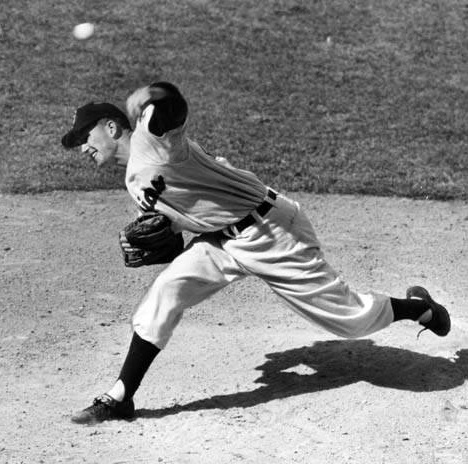

Dick Allen (15), presumed launching a baseball toward LaGuardia Airport’s flight line (he’s hitting against the Mets here) . . .

Some time around Opening Day, I spotted an online baseball forum participant huff that he didn’t want to see a particular player in the Hall of Fame because, well, the man fell far short of 3,000 major league hits. I have no idea whether it crossed his radar that drawing and enforcing lines like that would send some of baseball’s genuine greats out of Cooperstown.

Some who concurred I’d known to defend the Hall election of a 22-season man, himself short of the Magic 3,000, whose sole apparent credential for the Hall was being a 22-season man. That’s the Gold Watch Principle at work. Longevity in baseball is as admirable as it is non-universal, but merely having a very long career isn’t the same thing as having Hall of Fame-worthy career value.

More Hall of Famers than you often recall earn their plaques despite somewhat short careers and/or by their peak values above their career values. They only begin with Dizzy Dean, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Sandy Koufax. And the player the aforementioned forum denizen doesn’t think should be in the Hall of Fame has a bona-fide, peak-value Hall case.

This player was a middle-of-the-order hitter who hit frequently, and often with power described politely as breathtaking and puckishly (by Hall of Famer Willie Stargell) as the kind that causes boos because they don’t stay to become fan souvenirs. He was run productive to extremes at his absolute peak, but I’m not going to truck with the runs he scored and those he drove in too much for a very good reason: Those are impressive, and valuable, and entirely team-dependent.

Unless you think he could score when those behind him couldn’t drive him home (unless he reached third and could steal home at will), or drive in runs if those ahead of him in the lineup couldn’t reach base (never mind his power, even he couldn’t hit home runs far enough to allow time for two to four trips around the bases before the ball landed), answering “yes” to either means you shouldn’t hang up your shingle as a baseball professor just yet.

What we should want to know, really, is what he brought to the table by himself, when he checked in at the plate or hit the bases when healthy and not buffeted by too many controversies not entirely of his own making.

We should look at his plate appearances (PA), not his official at-bats, because the latter don’t offer the complete, accurate story of what he did at the plate to create runs for his teams. We should look at his total bases (TB), which treats his hits unequally, as it should be, because all hits are not equal. (If you think a single is equal to a double, a double equal to a triple, a triple equal to a home run, better keep the shingle in its original packaging for now.)

We should look at how often he hit for extra bases. (XBH.) (We should also look at how often he took the extra base on followup hits: XBT.) And, we should look at his real batting average (RBA)—his total bases, his walks, his intentional walks, his sacrifices, divided by his total plate appearances. The traditional batting average should really be called a hitting average, because it divides hits by official at-bats only and implies (incorrectly) that all hits are equal.

What I wanted to know along the foregoing lines is everything this player did to create runs.

When I first pondered the RBA concept I didn’t include intentional walks. But while I began revisiting this player it hit me. Why not include them? They’re not what you work out with your acute batting eye and plate discipline, but you should damn well get credit for being so formidable a plate presence that a pitcher would rather you take first base than his head off.

With all the foregoing understood, I hope devoutly, here are the absolute peak seasons of the player in question:

| Year |

PA |

TB |

BB |

IBB |

SAC |

HBP |

XBH% |

XBT% |

RBA |

| 1964 |

709 |

352 |

67 |

13 |

9 |

0 |

40 |

52 |

.622 |

| 1965 |

707 |

306 |

74 |

6 |

12 |

2 |

35 |

57 |

.566 |

| 1966 |

599 |

331 |

68 |

13 |

4 |

3 |

45 |

70 |

.699 |

| 1967 |

540 |

262 |

75 |

18 |

1 |

1 |

45 |

53 |

.661 |

| 1968 |

605 |

271 |

74 |

15 |

9 |

1 |

43 |

63 |

.611 |

| 1969 |

506 |

251 |

64 |

10 |

4 |

0 |

46 |

55 |

.650 |

| 1970 |

533 |

257 |

71 |

16 |

1 |

2 |

44 |

49 |

.651 |

| 1971 |

649 |

257 |

93 |

13 |

6 |

1 |

30 |

53 |

.570 |

| 1972 |

609 |

305 |

99 |

16 |

3 |

1 |

45 |

48 |

.696 |

| TOTAL |

5457 |

2592 |

685 |

120 |

49 |

11 |

41 |

56 |

.636 |

| 162G Avg. |

688 |

327 |

87 |

16 |

8 |

2 |

42 |

57 |

.640 |

That should resemble a peak value Hall of Famer to you whether or not you marry it to his slash line for those nine seasons: .298 hitting average (sorry, I’m sticking to the program here), .386 on-base percentage, .550 slugging percentage, .936 OPS (on base plus slugging), and 164 OPS+.

He did it while playing in a pitching-dominant era and while being perhaps the single most unfairly controversial player of his time, especially during the first six of those seasons:

| Years |

PA |

TB |

BB |

IBB |

SAC |

HBP |

XBH% |

XBT% |

RBA |

| 1964-1969 |

3666 |

1773 |

422 |

75 |

39 |

7 |

42 |

58 |

.632 |

| 162G Avg. |

693 |

336 |

80 |

15 |

8 |

2 |

43 |

59 |

.636 |

The player is Dick Allen.

When the Golden Era Committee convened in 2014, Allen missed Hall of Fame election by a single vote. So did his contemporary and co-1964 Rookie of the Year Tony Oliva. Allen missed despite that committee having more members with ties to his career than the Today’s Game Committee had to Harold Baines when electing him, very controversially, a few months ago.

Allen and Oliva have things in common other than missing their last known Hall of Fame shots by a single vote each. They both had fifteen-season major league careers. They both missed the Sacred 3,000 Hit club. (Hell, they both missed the 2,000-hit club.) They both hit around .300: Oliva, .304 lifetime; Allen, .292. And they both had careers rudely interrupted then finished by too many injuries.

Past that, let’s look at their lifetime averages per 162 games where they count the most:

| 162G Avg. |

PA |

TB |

BB |

IBB |

SAC |

HBP |

XBH% |

XBT% |

RBA |

| Dick Allen |

678 |

327 |

87 |

16 |

8 |

1 |

42 |

53 |

.647 |

| Tony Oliva |

665 |

290 |

43 |

13 |

7 |

6 |

31 |

47 |

.540 |

Now, let’s look at those parts of their slash lines that matter the most. If you wish to argue as many still do that a .304 lifetime hitting average makes Tony Oliva the superior hitter to a Dick Allen with a lifetime .292 hitting average, be my guest—after you ponder:

| 162 G Avg. |

OBP |

SLG |

OPS |

OPS+ |

| Dick Allen |

.378 |

.534 |

.912 |

156 |

| Tony Oliva |

.353 |

.476 |

.830 |

131 |

Especially if you consider that their primes came during an era where a) they were up against some of the toughest pitching in the game’s history and b) hitting in conditions that gave far more weight to pitching overall than to hitting overall, both these players have firm peak-value Hall of Fame cases. Tony Oliva deserves the honour, too, but Dick Allen was a better player.

Allen had more power, more speed, was feared more considerably at the plate, and took a lot more extra bases on followup hits helping him be more run creative. And even in his seasons with Connie Mack Stadium as his home ballpark, Allen had slightly tougher home parks in which to hit than Oliva did. Let’s compare their peaks:

| 162 Game Avg. |

PA |

Outs |

RC |

RC/G |

| Dick Allen |

688 |

441 |

129 |

7.8 |

| Tony Oliva |

694 |

465 |

113 |

6.5 |

You’re not seeing things. Allen at his peak, per 162 games, used 24 fewer outs to create 16 more runs. By the way, assuming the home run hasn’t turned you off yet, given fifteen completely healthy seasons each and allowing for a normal decline phase if they hit one by ages 35 (Allen) or 37 (Oliva), Oliva might have hit a very respectable 315 . . . but Allen might have hit 525. Maybe more.

Other than each missing enshrinement by a single vote in 2014, the most compelling reason to compare the two is that people married to baseball know Oliva’s injury history kept him from making his case more obvious (as would those of Dale Murphy and Don Mattingly, and neither of them were as good as Allen and Oliva) but often forget how Allen’s injury history kept the seven-time All-Star from making his case more obvious.

Because, you know, there was, ahem, that other stuff. The stuff that earned Allen a reputation as a powder keg who earned Bill James’s dismissal (in The Politics of Glory, later republished as Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?) of the wherefores:

Dick Allen was a victim of the racism of his time; that part is absolutely true. The Phillies were callous to send him to Little Rock in 1963 with no support network, and the press often treated Allen differently than they would have treated a white player who did the same things. That’s all true.

It doesn’t have anything to do with the issue . . . Allen directed his anger at the targets nearest him, and by doing so used racism as an explosive to blow his own teams apart.

Dick Allen was at war with the world. It is painful to be at war with the world, and I feel for him. It is not his fault, entirely, that he was at war with the world . . .

He did more to keep his teams from winning than anybody else who ever played major league baseball. And if that’s a Hall of Famer, I’m a lug nut.

If names such as Hal Chase, Rogers Hornsby, Albert Belle, and Barry Bonds sound familiar, it’s an extremely ferocious stretch to put Dick Allen at the top of that heap. It’s also a ferocious stretch if you know the complete story of the 1964-69 Phillies. Which you can get from one splendid book, William C. Kashatus’s September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration, from 2004.

Left to right: infielder Cookie Rojas, outfielder Johnny Callison, third baseman Dick Allen, manager Gene Mauch, 1964. The Phillie Phlop wasn’t anywhere near Allen’s fault . . .

Allen wasn’t even close to the reason for the infamous Phillie Phlop. During September/ October 1964 he posted a 1.052 OPS. Kashatus exhumed the real reason the Phillies didn’t stay truly pennant-competitive again for the rest of the 1960s: a slightly mad habit of trading live young major leaguers and prospects (including Hall of Famer Ferguson Jenkins) for veterans well established but on the downslopes of once-fine careers.

The Phillies had winning records from 1965-67, but that habit began catching up to them in earnest starting in 1968—coincidentally, the season during which Allen really began trying to force the Phillies to send him the hell out of town. But Kashatus and other chroniclers—particularly Craig Wright, a Society for American Baseball Research writer debunking James—have also affirmed that Allen went out of his way to keep his teammates away from any of his desperation antics.

Just ask Bob Skinner, the former Pirate outfielder who succeeded Gene Mauch as the Phillies’ manager in 1968, and who tangled with Allen only over Allen’s bid to dress away from the clubhouse to keep himself from affecting his mates:

We certainly weren’t a bad team because of him. I didn’t appreciate some of his antics or his approach to his profession, and I told him so, but I understood some of it. I do believe he was trying to get [the Phillies] to move him. He was very unhappy. He wanted out. There were people in Philadelphia treating him very badly . . . He obviously did some things that weren’t team oriented, but his teammates did not have a sense of animosity toward him. Not that I saw. They had some understanding of what was going on.

Allen grew up in a strong family, raised by a strong but loving mother (he bought her a new home with his $70,000 signing bonus from the Phillies), in a small, integrated area in Pennsylvania farm and mine country, integrated well enough that black and white children thought nothing of having sleepovers in each other’s homes, even if they might not have dated each other.

Little Rock, Arkansas, was Allen’s first explicit taste of Southern-style racism and his 1963 experience seared him, as well it might have, when sent there for his AAA finishing with no warning of what he was likely to face as the first black player on the Travelers. There were those who wondered why Allen couldn’t take his cue from his hero Jackie Robinson’s experience of a decade and a half earlier.

But Robinson was a 27-year-old Army veteran and Negro Leagues veteran when the Dodgers brought him first to their Montreal farm and then to Brooklyn, and Branch Rickey and company prepared him as thoroughly as possible for facing and surviving the league’s bigots. Allen was 20 when promoted to Little Rock and entirely on his own. As he said himself in his eventual memoir (Crash):

Maybe if the Phillies had called me in, man to man, like the Dodgers had done with Jackie Robinson, and said, “Dick, this is what we have in mind. It’s going to be very difficult but we’re with you”—at least I would have been prepared.

The notorious Philadelphia race riot of 1964, occurring while the Phillies were on a road trip, left white Philadelphia very much on edge and presented the Phillies’ black players as a potential target. But the real first shot of what became Allen’s war was fired 3 July 1965, around the batting cage before a game. The culprit was veteran first baseman/ outfielder Frank (The Big Donkey) Thomas.

Needled by All-Star outfielder Johnny Callison after a swing, Thomas retaliated against Allen–hammering Allen with racial taunts, including “Richie X” and “Muhammad Clay.” Thomas had already infuriated no few teammates, black and white, with a pattern of race baiting, against Allen and other black Phillies, but now Allen finally had enough.

All things considered Thomas should have considered himself fortunate that all he got was Allen punching him in the mouth. But Thomas retaliated by swinging his bat right into Allen’s left shoulder. Those who were there have since said it took six to get Allen off Thomas. And when the brawl settled, manager Mauch made a fatal mistake. Not only did he force Thomas onto release waivers but he ordered Allen, Callison, and all other Phillie players to keep their mouths shut about the brawl or be fined.

Which gave the departing Thomas all the room he needed to bray about it, which he did in a radio interview, accusing Allen of dishing it out without being able to take it and saying the Phillies unfairly punished one (himself) without punishing the other. That’s gratitude for you: Allen actually tried to talk the Phillies out of getting rid of Thomas, out of concern for Thomas’s large family.

Under Mauch’s threat, Allen and his remaining teammates couldn’t deliver the fuller story. That allowed Philadelphia’s sports press of the time to make room enough for the extreme among racist fans to hammer Allen with racial taunts, racial mail, death threats, litter on his lawn (if and when they discovered where he lived), and objects thrown at him on the field, enough to prompt his once-familiar habit of wearing a batting helmet even on defense. (Hence his nickname Crash.)

Already unable to accept Allen as an individual, from rejecting his preferred name (Dick) in favour of one he considered a child’s name (Richie) to out-of-context quoting of him when he did speak out, those sportswriters roasted him at every excuse, even abetting or refusing to investigate the most scurrilous and unfounded rumours about him. The nastiest probably involved the 1967 injury Allen suffered trying to push his stalled car back up his driveway, with speculation that he’d either been stabbed in a bar fight or gotten hurt trying to escape when caught inflagrante with another woman.

Allen didn’t hit as well the rest of 1965 as he had before Thomas smashed into his shoulder with the bat. He overcame a partial shoulder separation in 1966, but the driveway injury severed right wrist tendons enough to require a five-hour surgery to repair them, costing Allen some feeling in two fingers and making it difficult to throw a ball across the infield (which finally made him a near full-time first baseman) or in from the outfield (where he’d also play periodically).

And despite those injuries and those pressures, Allen led the National League with a .632 slugging percentage, a 1.027 OPS, and a 181 OPS+ in 1966; and, on-base percentage (.404), OPS (.970), and OPS+ (174) in 1967. Wright exhumed that Mauch believed to his soul Allen really began wanting out of Philadelphia after the wrist injury rumours.

Introverted by nature, Allen still made friends among black and white teammates alike. He enjoyed talking to younger fans who weren’t possessed of their parents’ bigotries. He smarted over the hypocrisy of fans taunting him and throwing things at him one minute exploding into raucous cheers over yet another monstrous home run the next. He also tried playing through his injuries career-long until their pain became too much to bear.

“Dick’s teammates always liked him,” Mauch himself once said. “He didn’t involve his teammates in his problems. When he was personally rebellious he didn’t try to bring other players into it.” Like perhaps too many overly pressured young men, Allen took refuge in drink, often stopping at watering holes to or from the ballpark. Most of them didn’t have to deal with his so often unwarranted public pressures.

Allen’s possible closest white friend on the Phillies was catcher Clay Dalrymple, who eventually told Kashatus he wondered why Allen—who was known even in Philadelphia for mentoring players without being asked—wouldn’t take the explicit, overt team leadership role Mauch tried to convince him to accept:

It was right there for him to take if he wanted it. “All you have to do is learn how to talk with the press,” I told him. “I’d rather let my bat do my talking and be a team player,” he told me. Well, that was typical [Dick]. He never wanted to tell others what to do, probably because he didn’t like being told what to do.

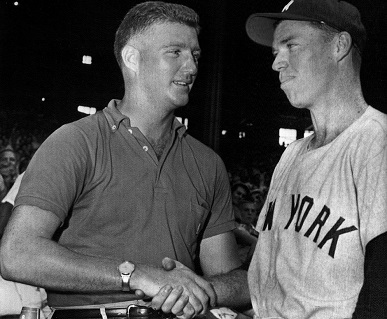

Allen as a Cardinal (right) holding Hall of Famer Willie Stargell on first. Stargell once kidded that Allen got booed because “When he hits a home run, there’s no souvenir.”

Finally the Phillies promised to trade him after the 1969 season. And they did. They traded him to the Cardinals for Curt Flood. Oh, the irony. To Flood, the deal meant he was still a slave at the mercy of his owners; to Allen, who rooted for Flood’s coming reserve clause challenge, the deal was tantamount to the Emancipation Proclamation.

He had a solid 1970 in St. Louis despite Busch Stadium being a far tougher hitter’s park than Connie Mack Stadium and despite a bothersome Achilles tendon and, later in the season, a torn hamstring. He had a solid 1971 with the Dodgers despite Dodger Stadium making Busch Stadium resemble a hitter’s paradise.

Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst, edgy about acquiring Allen originally, was anything but by the time Allen was traded:

He did a real fine job for me. He had a great year, led our team in RBIs, and he never gave me any trouble . . . He was great in our clubhouse. He got along with everybody. He wasn’t a rah-rah guy, but he came to play. They respected him, and they liked him.

The Cardinals traded Allen to the Dodgers not because of any divisiveness issues but because they needed the young second baseman (Bill Sudakis) they didn’t have yet in their own system behind Julian Javier, the veteran coming toward the end of a solid career. The Dodgers traded Allen to the White Sox (for Tommy John) because his reticence about scripted public appearances didn’t jibe with owner Walter O’Malley.

Allen with the White Sox: “He played every game as if it was his last day on earth,” said his manager there, Chuck Tanner.

He exploded with the White Sox in 1972, yanking them into pennant contention and winning the American League’s Most Valuable Player Award, then suffered injuries yet again in 1973 and 1974. In spite of which he led the league in home runs (1972, 1974), on-base percentage (1972, also leading the Show), slugging (1972, 1974, the latter also leading the Show), and OPS. (1972, which also led the Show; and, 1974.)

He retired before the 1974 season ended, ground down by the injuries, but he let a very different group of Phillies (Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt led a group to Allen’s Pennsylvania farm) talk him into returning for a final go-round in 1975-76. But the injuries finally extracted their penalties in earnest. After one brief spell with the 1977 Athletics, Allen retired.

White Sox manager Chuck Tanner, who’d known Allen’s family for years as neighbours and had the respect and affection of Allen’s beloved mother, and who was the key in Allen accepting the deal that sent him there:

He was the greatest player I ever managed, and what he did for us in Chicago was amazing . . . Dick was the leader of our team, the captain, the manager on the field. He took care of the young kids, took them under his wing. And he played every game as if it was his last day on earth . . . He played hurt for us so many times that they thought he was Superman. But he wasn’t; he was human. If anything, he was hurting himself trying to come back too soon.

Bill Melton, third baseman and Allen’s best friend on the White Sox and still a White Sox broadcast commentator:

[M]ost of all he led by example, and had a calming effect on the younger players. He just made us better as a team . . . It meant a lot to him that his teammates befriended him pretty quickly after he was traded here. The young kids loved him, especially the pitchers, because he took the time to mentor them. And the fans cared about him, too. There’s no doubt in my mind that Dick was one of the most beloved players in the history of the White Sox organisation.

Hall of Fame relief pitcher Goose Gossage, a rookie on the 1972 White Sox:

Dick’s the smartest baseball man I’ve ever been around in my life. He taught me how to pitch from a hitter’s perspective and taught me how to play the game and how to play the game right. There’s no telling the numbers this guy could have put up if all he worried about was his stats.

As in Philadelphia, injuries got directly in the way of Allen’s total raw numbers. Enough that White Sox GM Hemond had to defend Allen against accusations by Chicago Sun-Times writer Jerome Holtzman that he was really malingering rather than fighting what proved a leg fracture:

Once we fell out of the pennant race we had to begin thinking about [1974]. We decided that rather than push him and risk further injury to his leg it would be better if Dick sat out and fully recuperated so he’d be ready to go for the next season. Why jeopardise his future for a few extra times at bat?

Allen eventually admitted how immature he’d been in a lot of the ways he’d handled his first Philadelphia tour of duty. Some still believe such immaturity shortened his career. Writing in The Big Book of Baseball Lineups, Rob Neyer rebuked his one-time employer Bill James: “I don’t think his immaturity had much to do with the length of his career. He just got hurt, and so he didn’t enjoy the sort of late career that most great hitters do. It’s that, as much as all the other stuff, that has kept him out of the Hall of Fame”

Calling everything else that buffeted Allen just “all the other stuff” does him a disservice no matter his eventual admission of foolishness trying to beat it back. If anything, it’s to wonder that Allen could have played as well as he played through both the injuries and “all the other stuff.”

Allen might have been given another Hall of Fame shot last year but for his re-classification for the Golden Days Era Committee, which addresses players whose biggest impacts were between 1950-1969, and doesn’t convene again until 2020. Which means that if they elect Allen, he’ll be inducted in 2021.

A man who has endured heartache above and beyond what he was put through in Arkansas and his first Philadelphia tour—a painful divorce, the unexpected death of his daughter, the destruction (electrical fire) of the farm on which he’d hoped to breed thoroughbred horses (asked once about Astroturf, he deadpanned memorably, “If my horse can’t eat it, I don’t want to play on it”)—Allen, who has since remarried happily and keeps his family and friends close, can take or leave the Hall of Fame by himself.

“What I’ve done, I’m pretty happy with it,” he told Kashatus once. “So whatever happens with the Hall of Fame, I’m fine with. Besides, I’m just a name. God gave me the talent to hit a baseball, and I used it the best I could. I just thank Him for blessing me with that ability and allowing me to play the game when I did.”

Jay Jaffe, in The Cooperstown Casebook, gave Allen the first half of his introduction to the chapter on third basemen::

[C]hoosing to vote for him means focusing on that considerable peak while giving him the benefit of the doubt on the factors that shortened his career. From here, the litany is sizable enough to justify that. Allen did nothing to deserve the racism and hatred he battled in Little Rock and Philadelphia, or the condescension of the lily-white media that refused to even call him by his correct name. To underplay the extent to which those forces shaped his conduct and his public persona thereafter is to hold him to an impossibly high standard; not everyone can be Jackie Robinson or Ernie Banks. The distortions that influenced the negative views of him . . . were damaging. To give them the upper hand is to reject honest inquiry into his career.

During Allen’s first Philadelphia tour some fans who rooted for him no matter what hung a banner in the left field upper deck emblazoned with a target framed by two words: “Allen’s Alley.” An honest inquiry into his career should tell you his peak value means Allen’s Alley should lead to Cooperstown at last.