Pete Rose, in his early Reds seasons.

The true cynic must have been awfully tempted to note the date and believe that, once again, Pete Rose made something bigger than him about him. Rose died Monday, at 83, when the Atlanta Braves and the New York Mets tangled in a postseason-decisive doubleheader.

“He couldn’t have done it better,” that cynic might think, “if he’d held out for Game One of the World Series.”

The charitable is tempted to think likewise that even Rose wasn’t and wouldn’t have been that crass about his passage from this island Earth. Would he? He’d already had too deep a roll of “untrustworthy behaviour,” as The Athletic‘s Ken Rosenthal phrased it almost two years ago. He had an equivalent roll of proclaiming enough of his controversies and troubles were someone else’s fault.

“He was Icarus in red stirrup socks and cleats,” wrote his most recent and possibly most thorough biographer, Keith O’Brien, in Charlie Hustle: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball. “He was the American dream sliding headfirst into third. He was both a miracle and a disaster, and he still is today.”

Few historically great baseball players could be Rose’s level of being their own best friends and their own worst enemies. Those players discovered the hard way when their careers turned toward the decline phases or ended outright. None of those players took either to Rose’s extremes.

O’Brien has written an elegy in the Los Angeles Times in which he, a fellow Cincinnatian, recalls the code by which Rose was raised in the city’s West Side neighbourhoods: “to look both ways when crossing U.S. 50, to be home by supper, to fight for everything in life and to never speak ill of the dead.”

Rose fought for whatever he could and did achieve as a baseball player, the under- endowed, skinny kid who willed himself above and beyond his presumed station to become one of baseball’s biggest stars.

Rarely if ever did it occur to those covering him and falling into thrall to his on-field extremism and off-field wit that Charlie Hustle had a darker, danker side that even opposing GMs ignored because he was a gate attraction on the road as well as at home. “Sportswriters celebrated him for his grit and determination,” O’Brien writes, “and happily ignored his obvious flaws: his womanizing, his gambling and his apparent addiction to both.”

It was an easy choice for the writers. Rose was charming, loved to talk about baseball and always made light of any concerns about his propensity to get down a bet. He admitted being addicted to gambling only later, and only when it served him. The first time was in 1990, when he was seeking leniency in his federal sentencing for tax evasion, and he acknowledged it again in 2004, when he published a shallow, self-serving memoir that he hoped would get him reinstated to baseball.

In reality, Rose was horribly addicted in ways he’d never truly acknowledge. He couldn’t stop gambling. Many people knew it—journalists, Major League Baseball officials, the Reds’ management, his friends, even ordinary fans—and in the end they all just watched him fall.

“The Reds have covered up scrapes for Pete his whole career,” said then-Orioles general manager Hank Peters, after Rose’s 44-game hitting streak ended. “He’s always been in some little jam . . . but people never seem to hold it against him.” Said Rose’s one-time boss on the Reds, Dick Wagner, “Pete’s legs may get broken when his playing days are over.”

Commissioner Peter Ueberroth forced himself to hand the original Rose investigation over his gambling to successor A. Bartlett Giamatti, who’d learn the hard way what disappointed Ueberroth: Rose couldn’t and wouldn’t admit what he’d done. He’d spend years denying it despite the evidence and his banishment . . . until, as Rosenthal reminded us, he wrote a self-serving memoir whose title (My Prison Without Bars) said more than he probably intended.

Rose’s permanent banishment from MLB for violating the rule that prohibits betting on one’s team (and does not specify whether it’s betting your team to win or lose) was followed by the Hall of Fame (which is not under direct MLB jurisdiction, even though baseball’s commissioner serves on its board) voting to bar those on baseball’s permanently ineligible list from appearing on any Hall ballot.

As usual, even if the provocateur is his death, Rose provokes an all-around debate between those who cling to their faith that he was handed a raw deal, those who cling to their equivalent faith that he got precisely what baseball’s rules mandated, and those who cling to the erroneous belief that what he was handed was a “lifetime,” not a “permanent” banishment from the game he loved and besmirched.

There’s even a debate over the shouldn’t-be-debatable, Rose’s verified extramarital dalliance with a girl under Ohio’s legal age for sex. (The long-since grown up girl revealed it in a sworn statement in defense of John Dowd, whom Rose sued for defamation after Dowd cited him for statutory rape. Rose said he didn’t know she was under age at the time . . . but settled with Dowd out of court.) Some simply don’t discuss it. But plenty of others pour a triple shot of appropriate outrage.

Another Athletic writer, C. Trent Rosecrans, went outside Cincinnati’s Great American Ballpark after the news broke Monday, to where a statue of Rose in one of his entertaining and often reckless headfirst slides sits. The statue’s base was covered with everything from roses to baseballs on which Reds fans wrote messages to him.

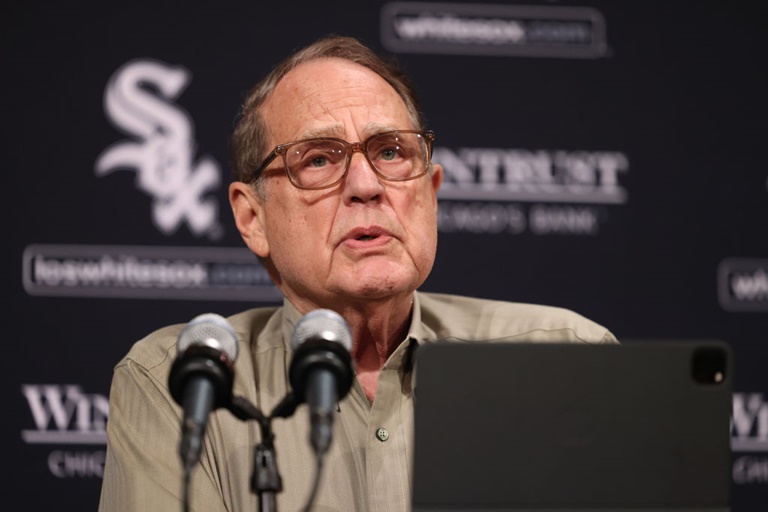

Possibly the last known photograph of Rose, appearing at a card show with former Reds teammates (l to r) Dave Concepción, George Foster, Tony Perez, and Ken Griffey, Sr., the day before Rose’s death.

“Outside of Cincinnati, Rose’s legacy is complicated,” Rosecrans writes. ” . . . Here, it’s less complicated. ‘He is Cincinnati,’ [Geoff] Moehlman said. ‘Hard-working town. Hard-working player’.” But O’Brien also remembered in his book that, when Rose became the Reds’ first back-to-back batting titlist, Ohio’s governor proclaimed Pete Rose Day, Cincinnati chose to rename his favourite childhood park after him, but at least five hundred Cincinnatians signed a petition opposing that renaming.

“They didn’t think Pete Rose was worthy of a local landmark,” O’Brien wrote, “perhaps because there were growing questions and rumors about him—questions and rumors that even West Siders couldn’t ignore. One of the rumors circulating about Pete concerned gambling. He seemed to do a lot of it.”

That was before Rose made his first bet with an illegal bookmaker in Cincinnati in the early 1970s. That revelation at that particular time could have brought Rose a discretionary commissioner’s suspension, such as the full year Happy Chandler banned Leo Durocher for hanging with bookies or the full year Bowie Kuhn banned Denny McLain for being a bookie. Maybe it would have been an awakening for Rose almost two decades before he got the one he didn’t want.

The petition against renaming his childhood park for him was also before his womanising reached the point that he faced and lost a paternity suit in 1979. Before he went out of control and into debt enough with his gambling that—not long after becoming the Reds’ player-manager, but while he still held both jobs, in April 1986—Rose did for the first time what he’d never entertained previously: bet on baseball.

He once said, famously enough, “I was raised, but I never grew up.” That’s not entirely true. He had a moral side. The side that enabled him to befriend minority players on his early Reds teams. The side that spurred him to help rookies who followed him and traded-for veterans alike acclimate. The side that compelled him to say to Hall of Famer Carlton Fisk, during Game Six of the 1975 World Series, “This is some kind of game, isn’t it?”

The side that refused to let him even think about a sacrifice bunt against the Cubs in Chicago, when he batted with the Reds still in a piece of a 1985 pennant race, big Dave Parker on deck, and everyone from his boss Marge Schott to Joe and Jane Fan all but demanding he sacrifice and save what he called the Big Knock (passing Ty Cobb, whom he’d already met on the road, on the all-time hits parade) for the home audience.

The side that manager Rose used to order player Rose—knowing a bunt meant a free pass to Parker, lesser bats handed the high-leverage hitting, far less chance for a Reds win—to hit away. Into the most honourable strikeout of his career. (Maybe it was the least he could do on the approach after hanging around to chase Cobb down for far longer than his real usefulness as a player really lasted. But still.)

That’s the side obscured by the manchild who could no longer charm his way out of having mistaken recklessness for invincibility.

I was raised, but I never grew up. The tragedy isn’t that Rose will remain banished from baseball or blocked from the Hall of Fame. The tragedy is that Rose alone wrote the script that sent him there.