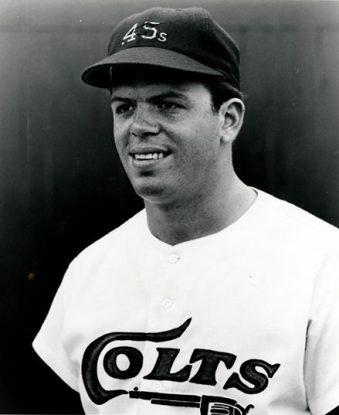

Larry Yellen–He shared a rookie card with eventual Miracle Met Jerry Grote . . . and had to miss being part of an all-rookie Colts starting lineup because the game would happen on Yom Kippur. (Photo from Jewish Baseball Museum.)

With the eyes of baseball world upon Tuesday’s trading deadline, and upon whom among the big enchiladas might be moving where, something happened almost too quietly to notice. Baseball’s government paid $185 million to settle litigation with minor league players who sued on grounds that minimum wage laws were violated.

According to the Associated Press, it’s going to work this way: 24,000 players from 2009 through last year are eligible to share the money. The estimated payments will range between $5,000 and $5,500. The money’s been transferred to JND Legal Administration. The AP says they plan to make the payments by 14 August.

The settlement covers all players with minor league contracts who played in the California League for at least seven straight days starting on Feb. 7, 2010, through the settlement’s preliminary approval last Aug. 26; players who participated in spring training, extended spring training or instructional leagues in Florida from Feb. 7, 2009, through last Aug. 26; and players who participated in spring training, extended spring training or instructional leagues in Arizona from Feb. 7, 2011, through last Aug. 26.

The original plaintiffs filing in 2014 were Aaron Senne (1B/OF, Marlins system), Michael Liberto (IF, Royals system), and Oliver Odle (P, Giants system.) Senne retired before the suit was filed; Liberto and Odle have retired long since.

Last fall, of course, minor league ballplayers joined the Major League Baseball Players Association. This past spring, the minor league faction agreed to a five-year contract doubling all minor league player salaries, the AP said. That was nothing but good for the players, the union, and the game itself.

But you have to wonder. If the players’ union was willing to welcome minor leaguers into their ranks and back them on a five-year deal that jumped all their salaries, why can’t the union find a way to welcome and redress the issue of pensions denied what are now 500+ short-career major leaguers whose time in the Show came prior to the 1980 pension re-alignment?

At this writing, they haven’t, and it still looks as though they won’t. It also sounds as though they’ll continue to say what they’ve said too long about that pension redress: nothing.

The 1980 re-alignment started handing pensions to major leaguers who had 43 verified days on major league rosters and health benefits to those who had one verified day there. The kicker was that it went to major leaguers whose careers ended after 1980. Those who had 43 verified major league roster days before 1980? Oops.

Double oops: The union’s line then was that the majority of those pre-1980 short-career major leaguers were measly September call-ups. Not that that should matter a damn, but not so fast. Peruse the records of the 500+ and you should discover that the majority of them saw major league time:

* Prior to any September in any year.

* As early as April of any year.

* Making major league rosters out of spring training even once.

Allow me to mention a few of those pre-1980 players who have passed on to the Elysian Fields this year.

Larry Yellen (pitcher, Colt .45s: the Astros-to-be)—He was a September call-up in 1963 . . . but he appeared in thirteen games (twelve in relief) between 21 April and 3 October. He was sent back to the minors for August, brought back in September, then played one more season in the Houston system before leaving the game.

According to the Jewish Baseball Museum, Yellen nearly helped make a little history during September 1963: He would have been the starting pitcher late that month when the Colts elected to send an all-rookie lineup out against the Mets—until he made his debut the day before, thanks to the Mets game being scheduled on Yom Kippur.

Yellen’s post-baseball life proved a solid one. Though eventually divorced from his first wife, Yellen graduated from Fredonia State University in 1987, took up a life in sales and marketing, remarried happily, and eventually worked for a tutoring company until his retirement. He died at 80 on 18 July.

Yellen has another intriguing element in his baseball past: he shared a 1964 Topps rookie card with future Miracle Mets catching mainstay Jerry Grote.

Mike Baxes (middle infielder, Kansas City Athletics)—After seven prior minor league seasons, he looked promising when he came up to the Athletics in 1956, even as a classic good-field/little-hit middle infielder. But after a solid April 1957 followed by a regression at the plate, Baxes looked to be getting his swing back when he suffered an ankle fracture trying to turn a double play.

Traded to the Yankees, Baxes wasn’t likely to endure with established middle infielders Bobby Richardson and Tony Kubek nailing it down shut. He bounced around the PCL until the Buffalo Bisons—for whom he’d been a fan favourite before going up to Kansas City—took a chance on him. The injury drained more than anyone thought, and Baxes left the game in 1961.

His older brother, Jim, may have had a more lasting major league impression, alas: the elder Baxes hit his first home run off a Cardinals pitcher surrendering his first major league home run: Hall of Famer Bob Gibson. The elder Baxes died in 1996; the younger, at 92 on 13 April.

Pete Koegel (catcher/first baseman, Brewers, Phillies)—The first major league player from Long Island’s Seaford High School, Koegel is sort of a Ball Four footnote. He was one of a pair of minor leaguers traded out of the Athletics organisation to the Seattle Pilots—after the 1969 season ended, and before their move to Milwaukee to become the Brewers—for former Athletics pitcher and noted Jim Bouton nemesis Fred Talbot. (Talbot got into one game with the A’s before he called it a career.)

As a high school athlete, Koegel was named the MVP of the New York Journal-American‘s high school All-Star game—and was presented the award by no less than Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig’s widow, Eleanor. After his brief stints with the Brewers and the Phillies, Koegel played a few more years in the minor leagues (including the Mexican league) before calling it a career after 1977.

One of three 6’6″ catchers ever to see major league time, Koegel saw major league time in April 1971 before returning to the minors and being traded to the Phillies; and, for most of the season with the 1972 Phillies. He moved to Saugerties in upstate New York after leaving baseball, and spent the rest of his life in that region. He died at 75 on 4 February.

Ron Campbell (infielder, Cubs)—He was a September call-up in 1964 and 1965, but he appeared in June-July and then mid-August through the end of the season in 1966. His first major league hit (off Cincinnati’s mercurial John Tsitouris) drove a run home; his final day in the Show saw him have the second of a pair of lifetime three-hit games (against the Mets).

He spent four more years entirely in the minors before leaving baseball after 1970. He’d been a natural third baseman blocked by Hall of Famer Ron Santo, but he’d also been a highly regarded high school football and basketball player in his native Tennessee. In fact, he was inducted into the Chattanooga, Bradley County, and Tennessee Wesleyan Halls of Fame. He died at 82 on 2 February.

Those men died without seeing any full major league pension thanks to their 1980 re-alignment freezeout. The only thing they saw was a stipend arranged in a deal between then-Commissioner Bud Selig and then-players union executive director Michael Weiner: $625 per quarter for every 43 days’ worth of MLB time, up to four years’ worth. The stipend was hiked by fifteen percent in the settlement of the 2022-23 lockout.

But it still wasn’t a full pension. And Yellen, Baxes, Koegel, Campbell, and the remaining 500+ pre-1980 short-career major leagues couldn’t and still can’t pass the money on to their families upon their deaths.

The union’s first executive director, Marvin Miller, said originally, and perhaps accurately, that the union then didn’t have the money available. But he also said subsequently—and I’ve been told this by several of those pre-1980 players whom I’ve interviewed (and, in a few cases, befriended)—that a) when the money was there, they wouldn’t be forgotten; and, b) the union’s failure to re-visit the issue substantially was his biggest regret.

You might think that, if baseball’s government, presiding over a sport worth billions, could find $185 million to settle with minor leaguers, the players’ union—likewise said to have $56.8 billion in revenues—could find a way to do right by pre-1980 short-career major leaguers.

But you might first have to convince more than just a tiny handful of sportswriters to give the issue the airing it deserves. And that’s proven, thus far, to be about as simple as trying to sneak one past Shohei Ohtani.