If Bob Gibson tried to hit those who dared hit him for distance, he didn’t succeed even close to as often as his reputation suggests.

During an otherwise pleasant forum discussion, one member said this in the middle of a stream, regarding hit batsmen, replying to my assertion (about which I wrote) that Chris Archer deserved a suspension for drilling Derek Dietrich: “I’ve read/watched enough interviews with [Bob] Gibson to know he wasn’t just ‘brushing back’ batters—especially those who had hit a donga off him the time before. He was damn well trying to hit them.”

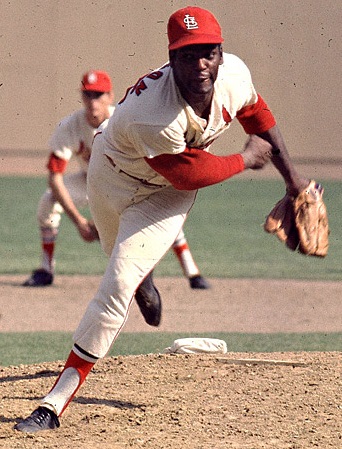

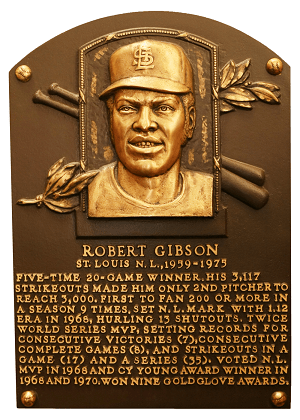

The mythology around the Hall of Fame righthander includes that Gibson took no quarter from any hitter and thought nothing of letting them have it if he thought they got too ornery at the plate. Gibson himself helped to foster the mythology, as he once told—well, one more time: Roger Angell isn’t baseball’s Homer; Homer was ancient Greece’s Roger Angell:

I did throw at [Mets outfielder] John Milner in spring training once. Because of that swing of his—that dive at the ball. I don’t like batters taking that big cut, with their hats falling off and their buttons popping and every goddam thing like that. It doesn’t show any respect for the pitcher. That batter’s not doing any thinking up there, so I’m going to make him think. The next time, he won’t look so fancy out there. He’ll be a better looking hitter.

“He had that hunger, that killer instinct,” said Joe Torre, a Gibson teammate in St. Louis and eventually his boss for a time, when Torre managed the Mets and named Gibson his pitching coach. “He threw at a lot of batters but not nearly as many as you’ve heard . . . Any edge you can get on the hitter, any doubt you can put in his mind, you use. And Bob Gibson would never give up that edge.”

Maybe not.

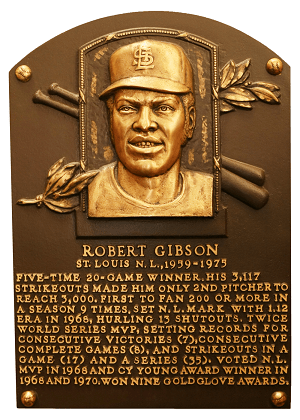

But Gibson is only number 84 on baseball’s all-time plunk parade. He hit 102 batters lifetime and averaged seven per 162 games lifetime. Look up the plunk parade. (And, quit laughing when you see a pair of knuckleballers, Tim Wakefield and Charlie Hough, in the top ten: the pitch is hard to control, has a mind of it’s own if the elements cooperate, and you shouldn’t be surprised that it’s liable to give a hitter a kiss now and then.) Don Drysdale, who lived on intimidation likewise, is in the top twenty.

Since my respondent in that forum talk insisted that Gibson was damn well trying to hit batters “especially those who had hit a donga off him the time before,” I just had to look it up. Crazily enough, I looked at the game logs for his entire major league career, all 528 games in which he pitched, all 482 times as the starting pitcher.

I fear my forum friend is going to be rather disappointed. Buckle up, it’s going to be a bit of a ride.

1960—Gibson didn’t have such a game until he faced Warren Spahn and the Braves on 12 September 1960. In the second inning, Gibson hit Wes Covington with a pitch to open the inning. The next batter, Joe Adcock, smashed a two-run homer.

The same two batters opened the fourth, with Covington drawing a walk and Adcock smashing a double to right. After Johnny Logan popped out foul, Chuck Cottier scored Covington with a sacrifice fly and Spahn himself doubled home Adcock to knock Gibson out of the game. One hit batsman, one home run, and the home run was hit after the plunk.

1961—Two games in which Gibson surrendered a homer and hit a batter. 17 April, vs. the Dodgers—Gibson surrendered a homer to Hall of Famer Duke Snider in the third, and hit Snider with a pitch when Snider batted again in the fifth. 3 May, vs. the Pirates—Gibson hit Rocky Nelson with a pitch leading off the fourth, and Nelson hit a two-out homer in the eighth for the only Pirate run of the game.

So far, the former Duke of Flatbush is the only one to take a hit from Gibson after taking him long distance.

1962—For the first time in his career, Gibson has four such games.

10 May, vs. the Giants—Gibson hit second baseman Chuck Hiller with a pitch in the fifth; Hiller was 0-for-2 in the game before that point. After Hall of Famer Willie Mays flied out to follow, fellow Hall of Famer Willie McCovey hit a three-run homer; with the Cardinals now down 5-0, Gibson was taken out of the game right after that bomb.

18 July, vs. the Cubs—In the top of the seventh, Gibson plunked Hall of Famer Ernie Banks with two outs, then surrendered a base hit to Hall of Famer Ron Santo before George Altman flied out for the side. The only Cub run of the game was courtesy of Hall of Famer Billy Williams hitting a solo bomb . . . in the top of the fourth; the Cardinals scored the pair that ultimately meant the game on Ken Boyer’s two-run double in the bottom of that inning.

Banks followed Williams in the lineup that day. If Gibson wanted revenge for Williams’s home run, why did he wait until the seventh to plunk Banks but not Williams?

7 September, vs. the Reds—The Cardinals jumped Bob Purkey for a pair of runs in the top of the first; in the bottom of the second, Gibson plunked Reds left fielder Marty Keough with two out before retiring the side. The game ended up in extra innings and in the tenth Hall of Famer Frank Robinson hit the game’s only home run and, after Jerry Lynch followed with a base hit, Gibson was lifted; the Reds won the game when Vada Pinson hit an RBI double in the bottom of the 11th off Curt Simmons.

11 September, also vs. the Reds—Gibson and Purkey went at it again. This time, Gibson hit the first batter of the game Eddie Kasko and paid for it promptly with an RBI triple (Don Blasingame) and a sacrifice fly (Pinson), putting the Cardinals in a 2-0 hole before they came up to the plate. In the top of the ninth, Kasko got even with Gibson, hitting a three-run homer to make it 6-2, Reds, before Purkey shook off a one-out infield error to finish the Cardinals off.

So far, Gibson has pitched seven games in his career in which he surrendered a home run and hit a batter in the same games, and only once has he hit a batter who homered off him previously in any game.

1963—The Cardinals make noise in the pennant race, hoping among other things to send Hall of Famer Stan Musial into retirement with a bang. Alas, they didn’t make it, but the Dodgers did, going on to sweep the Yankees in the World Series. How about the 1963 games Gibson pitched in which he was taken deep and hit a batter in the same games?

22 June, vs. the Dodgers—In the top of the second, Tommy Davis opened the scoring with a leadoff bomb off Gibson. Davis batted three more times in the game and, in order, walked and flied out to right twice. Gibson’s hit batsman in the game was former Yankee Moose Skowron . . . leading off the top of the seventh. (The Cardinals tied the game at one in the fifth on a run-scoring balk and got what proved the winning run in the sixth when Charlie James homered off Dodger rookie Nick Willhite.)

9 August, vs. the Braves—This time Gibson hit shortstop Roy McMillan twice—once after Denis Menke opened the bottom of the second with a double, and once after Menke hit a three-run homer with nobody out in the bottom of the third to put the Braves up 6-0. You can argue Gibson’s frustration over being in a 6-0 hole, of course, and Menke wasn’t exactly known as a power hitter, but Gibson could have waited to see Menke again (which he did, in the bottom of the fifth) instead of drilling McMillan a second time.

The final score was 6-3, Braves . . . and Gibson himself cut the deficit in half when he hit a two-run triple in the top of the fifth. But Menke himself didn’t pay for what proved the difference-making bomb.

28 August, vs. the Giants—Actually, Gibson didn’t hit anyone in this game . . . and the Giants took him deep four times in the game, including Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda and catcher Tom Haller hitting back-to-back bombs off Gibson in the bottom of the fourth, with Haller’s the second bomb he’d hit in that game. Haller batted twice more in the game; Gibson might have pitched him tight the first of those at-bats, allowing Cepeda to steal second, but he hit nobody in the game.

So far, still, Duke Snider’s the only one to get hit by Gibson his next time up after hitting one out, and by now that drill is two years old.

1964—The Cardinals won the pennant at literally the last minute, after the infamous Phillies collapse down the stretch and a closing weekend that could have sent the National League race into a three-way playoff.

Gibson himself factored in the closure, losing to the Mets’ stout little lefthander Al Jackson to open the final set, and the Cardinals losing again before Gibson on two days’ rest beat the Mets while the Reds lost to the Phillies, giving the Cardinals the pennant.

Now, what of the games in which he was hit for distance and plunked a hitter in the same contest?

9 May, vs. the Mets—In the Mets’ new Shea Stadium playpen, Gibson faced future pitching coach Galen Cisco. And guess who turned up playing shortstop for the Mets? Old Roy McMillan, whom Gibson drilled in the bottom of the second after catcher Jesse Gonder led off with a base hit. I don’t know whether or why Gibson would have a particular animus against McMillan, either.

By the time Gonder led off the bottom of the eighth with a home run the Cardinals had five runs on the board. (It might have been six but Dick Groat was thrown out at the plate trying to score behind Julian Javier on Bill White’s double.) Gibson also drilled Mets second baseman Ron Hunt in the ninth, but the Mets rookie was already earning his reputation for taking one for the team and Gonder wasn’t even close to looming in that inning.

15 July, vs. the Dodgers—With the Cardinals in the hole 7-1 by the top of the seventh, Gibson with one out drilled veteran Dodger infielder Junior Gilliam—who came into the game as a replacement at third base for the bottom of the sixth. The next batter, Dodger center fielder Willie Davis, hit a two-run homer.

With the Cardinals rallying in the bottom of the seventh, Gibson was lifted for a pinch hitter. The Dodgers went on to win the game with a four-run ninth, courtesy of home runs off reliever Ray Washburn—a three-run shot from Ron Fairly and a solo from Tommy Davis.

19 July, vs. the Mets—Gibson started the second game of a doubleheader versus Frank (Yankee Killer) Lary, the former Detroit righthander picked up by the Mets mid-season. This time, the Mets jumped early, with Gonder hitting a two-run homer in the top of the first with Hunt aboard. (After stealing second off his leadoff single, Hunt survived a pickoff thanks to a throwing error.)

It was the only home run in a wild enough game that ended with the Cardinals winning, 7-6. Gibson did hit Hunt with a pitch . . . in the top of the fourth, after Hunt got a second single in the game during a three-run Mets third.

So far, our survey says: Gibson has pitched twelve games in which he’s surrendered home runs and hit batters in the same game . . . and Duke Snider is still the only batter to hit one out off Gibson and get drilled his next time up. But if you look at that 19 July 1964 game against the Mets, you could make a case that maybe Ron Hunt annoyed Gibson enough reaching base without going long in two straight plate appearances prior that Gibson let him have it.

Could.

1965–This was Gibson’s first 20 game-winning season. But it wasn’t a good season for the defending World Series-winning Cardinals, who were struck by issues not of the players’ making going in and finished seventh, in a year the National League race belonged mostly to the pennant-winning Dodgers and the tight-on-their-trail Giants, who lost the pennant by two games.

They lost Series-winning manager Johnny Keane to the Yankees, thanks to one of the most notoriously underhanded double-switches in baseball history—after the Yankees fired Yogi Berra following that thriller of a seven-game Series. They spent 1965 getting used to new skipper Red Schoendienst. And they were demoralised after general manager Bob Howsam attempted salary cuts on several of his World Series-winning players.

Those are other stories for other times. We’re continuing our look at Gibson the homer-hating head hunter who wasn’t, quite, so far . . .

17 June, vs. the Pirates—Gibson plunked first baseman Donn Clendenon with two out in the top of the first; Pirates righthander Vernon Law answered by plunking Javier to lead off the bottom of the frame. In the fourth, Clendenon struck back with a leadoff single and Hall of Famer Willie Stargell promptly hit a two-run homer.

Stargell batted three more times in the game, striking out to end a 1-2-3 fifth, grounding out to end the seventh, and driving in the insurance run with a two-out RBI single in the ninth. Not once was he hit by a pitch after that fourth-inning bomb.

2 July, vs. the Mets—Gibson had a re-match with Frank Lary this time; the Mets had dealt Lary to the Braves during the 1964 stretch, for a kid pitcher named Dennis Ribant, then re-acquired Lary during spring training before dealing him to the White Sox not long after this game. (When the White Sox released him after the season, Lary retired.)

McMillan is still the Mets’ shortstop here . . . you guessed it: Gibson drilled him with one out and one on (Lary, a leadoff single) in the bottom of the fifth with the Cardinals up, 4-1. Former Cardinal Johnny Lewis sent the Mets’ second run home later in the inning with a base hit scoring Lary.

The Cardinals were up 6-2 in the bottom of the ninth when former Giant Chuck Hiller, now the Mets’ second baseman, hit a two-out homer, before Gibson got his old buddy McMillan to ground out to end the game.

31 July, vs. the Dodgers—This time, Gibson is up against Hall of Famer Don Drysdale, whom you’ll recall places way higher on the all-time plunk parade than Gibson does.

Now, unless you think Gibson was the Hunter Strickland of his time, there was no cause for him to drill Willie Davis in the top of the first to load the bases with nobody out a year after Davis took him deep. Gibson got the next three outs in order to strand the ducks on the Dodger pond, and the Cardinals had a 2-0 lead when Lou Johnson and Jim Lefebvre homered back-to-back in the top of the sixth to put the Dodgers up, 3-2.

Johnson and Lefebvre batted back-to-back in the eighth and popped out and flied out, respectively, in a 1-2-3 inning. Not a plunk between them. With Drysdale lifted for Ron Perranoski in the seventh, it looked like the Dodgers would bank a win until Hall of Famer Lou Brock walked it off with a two-run single in the ninth.

15 August, vs. the Reds—With one out and Hall of Famer Frank Robinson aboard in the top of the second, Gibson plunked Deron Johnson and paid for it—Johnny Edwards worked out a walk to load the bases, Leo Cardenas singled Robinson home keeping the ducks on the pond, and—after Reds starter Sammy Ellis looked at strike three—Pete Rose singled home Johnson and Edwards, before 1969 Mets hero-to-be Art Shamsky struck out for the side.

The Cardinals took the lead back in the top of the second, including Gibson himself hitting a three-run homer. But Johnson got revenge in the bottom, tying the game with a solo home run. He batted three more times in what turned into a 12-7 Cardinals win—flying out (off Gibson), doubling (off Gibson), and ending the game (off reliever Hal Woodeshick) with a fly out.

Edwards and Vada Pinson also homered in the game. The next time Edwards batted after his bomb, Gibson . . . walked him intentionally—in the inning Pinson led off by going long.

20 August 1965, vs. the Mets—Gibson beat Al Jackson and two relievers in this game. In the Mets third, with one out and one on, guess who got drilled again—Roy McMillan, whom Gibson struck out in the first. All things considered, there wouldn’t have been a jury on earth to rule McMillan unjustified if he felt like tearing apart Gibson limb by limb.

Charley Smith, the Mets’ third baseman, accounted for the only Mets run when he led off the bottom of the fourth with a home run. Smith batted twice more in the game, with a pop out to shortstop in the sixth and a game-ending fly out to center field.

For once in his life, Gibson himself got plunked when batting against Jackson with two out in the top of the fifth. (McMillan must have wanted to offer to have Jackson’s children right then and there.) The bad news for the Mets is that that mistake opened the door to a five run inning—a single, a double steal (Gibson to third, Brock to second), an RBI triple (Dick Groat), an RBI single (Curt Flood), and another RBI triple (Ken Boyer).

10 September, vs. the Phillies—This began as a match between a pair of Hall of Famers, Gibson and Jim Bunning. It ended in a 5-4 win for the Phillies, enduring their own struggles in the season that followed that heartbreaking pennant collapse.

With one out in the Philadelphia fourth, Gibson hit Johnny Callison with a pitch. Wes Covington promptly singled and Callison scored when Cardinals catcher Tim McCarver let a pitch get away, before Dick Stuart drove in Covington with a single for a 2-1 Phillies lead.

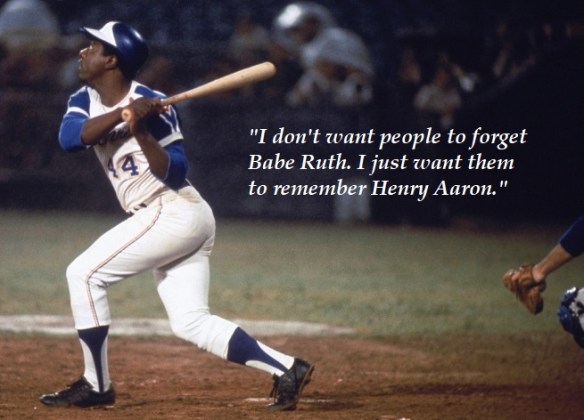

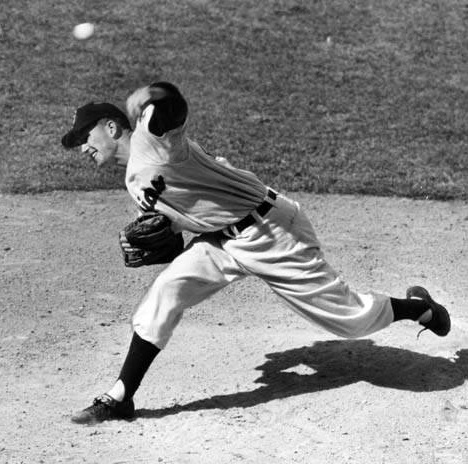

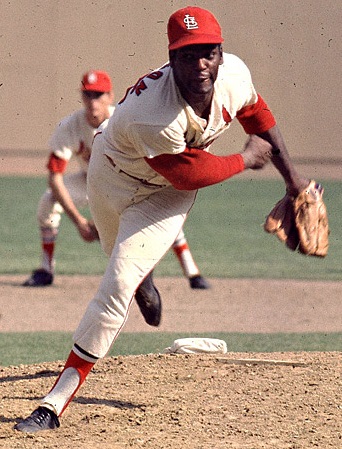

Gibson on the mound at the peak of his Hall of Fame career.

The game was tied at two in the bottom of the sixth when Stuart hit a two-out two-run homer; the Cardinals tied it at four in the eighth but the Phillies walked it off with Cookie Rojas’s RBI single off Woodeshick. Gibson never got another crack at Stuart in the game; he was removed for a pinch hitter in the seventh.

Survey says: Seventeen games lifetime to this point in which Gibson’s surrendered at least one bomb and hit at least one batter in the same game. Duke Snider is still the only man to get a Gibson drill after homering in a game. Snider retired after the 1964 season, but you could be tempted to wonder whether he was aware of his unique status when it came to dealing with Gibson.

Gibson led the National League in home runs surrendered on the season, by the way—with 37. He hit eleven batters on the year, too.

1966—With the Dodgers and the Giants going at it hammer and tongs in their last great pennant race against each other that decade, the Cardinals improved to sixth place. Gibson would be a 20-game winner for the second time, with a 21-12 won-lost record. He made his third All-Star team and won his second Gold Glove while he was at it.

14 May, vs. the Braves—Both Gibson and Braves starter Denny Lemaster went the distance with the Braves with Lemaster throwing a 3-0 shutout. With two on and one out in the fifth, Gibson plunked Mack Jones, 1-for-2 with a single to that point, to load the bases with Hall of Famer Henry Aaron coming up.

Aaron popped out foul and Joe Torre struck out to end the threat. Jones eventually accounted for the first Atlanta run with an RBI ground out in the seventh. With two out in the eighth Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews hit Gibson for a home run and Lemaster himself singled in the Braves’ third run later in the inning.

Gibson faced the Braves four more times that season and hit nobody with a pitch in those games.

22 May, vs. the Reds—Gibson beat Jim O’Toole and two Reds relievers, 4-3. Pinson homered off Gibson with two out in the bottom of the first; he flied out, struck out, and walked during the rest of the game but didn’t get hit by a pitch.

18 August, vs. the Dodgers—It was Gibson vs. Drysdale again with the Dodgers winning, 3-1. Willie Davis broke a one-all tie in the third with a two-out homer, then flied out in the sixth and grounded out to lead off the eighth. In the interim, Gibson hit . . . Lou Johnson with a pitch with one out in the fourth.

Now it’s twenty games in which Gibson surrendered a bomb and hit a batter in the same game. And Duke Snider still sits lonely at the top of that hit parade.

1967—This time, El Birdos (so nicknamed by Cepeda, who joined them in 1966) win the pennant . . . despite Gibson missing a month and a half after Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente fractured his leg with a line drive. Of course, Gibson would return to make life miserable enough for the Cinderella Red Sox in the World Series.

Gibson gave up ten bombs and hit three batters on the season. He didn’t pitch a single game that involved both a home run and a hit batsman at all, never mind in the same contest. Poor Snider.

1968—It looked like it was going to be deja vu all over again until Curt Flood misjudged Jim Northrup in Game Seven of the World Series, spoiling what had been Gibson’s magnificent Year of the Pitcher season (his 1.12 ERA; his thirteen shutouts) and Series pitching until then. It would be the last time Bob Gibson was seen in a World Series. Meanwhile, back in the jungle . . .

15 April vs. the Braves—The Cardinals won, 4-3, but Gibson lasted through seven with three runs surrendered before coming out, including Aaron’s two-run blast in the seventh. The man aboard, Atlanta infielder Sonny Jackson, got there thanks to . . . a Gibson plunk.

2 June, vs. the Mets—Game one of a doubleheader, Gibson vs. Al Jackson and one reliever in a 6-3 Cardinals win.

Bottom of the first: Second and third and one out, and Gibson drilled Mets catcher J.C. Martin. Bottom of the seventh: Ed (The Glider) Charles led off with a home run, for whatever that was worth. Charles batted against Gibson in the bottom of the ninth . . . and singled with two out, only to be stranded with unlikely World Series hero Al Weis (followup single) when Gibson ended the game by striking out former Cardinal Jerry Buchek.

11 September, vs. the Dodgers—Gibson went all the way to win his 22nd game of the year despite surrendering four earned runs . . . including veteran Willie Crawford’s game-opening bomb.

Crawford led off the third popping out to third base. Leading off the fifth, by which time the Cardinals had a cozy 5-1 lead, Gibson hit Crawford with a pitch. That wasn’t exactly the same as that 1961 plunk of Snider, since Crawford went through an in-between plate appearance unscathed. Crawford joins Snider—with an asterisk.

1969—Year one of divisional play. The Cardinals finish fourth in the NL East in the Year of the Miracle Mets. And when owner Gussie Busch—who was, otherwise, good to his players—dressed his players down as ingrates in spring training, in front of the press and his brewery directors, after the resolution of a pension plan dispute that threatened a possible strike or lockout, his players seethed.

“The speech demoralised the 1969 Cardinals. The employer had put us in our place. Despite two successive pennants, we were still livestock,” Curt Flood would remember. Shortly after that, the Cardinals traded Orlando Cepeda for Joe Torre, who was far from washed up, and who was well liked, but the deal meant beginning the breakup of the classic 1967-68 winners.

Meanwhile, on the mound with Gibson . . .

8 April, vs. the Pirates—Gibson went the distance in his first 1969 start, a 6-2 loss. Stargell cracked a leadoff homer in the top of the second, then singled in the fourth. Then Gibson hit Stargell with a pitch in the sixth—after Clemente singled home a run.

30 May, vs. the Reds—Gibson vs. Jim Maloney, still the Reds’ best pitcher despite increasing shoulder troubles. Again Gibson went the distance and lost, this time 4-3. But the Cardinals led 3-0 in the top of the seventh when Hall of Famer Johnny Bench hit a three-run homer to tie the game. Bench faced Gibson once more in the game without getting drilled but with a fly out to center to end the top of the ninth.

Bobby Tolan, however, did get a Gibson plunk with two out in the top of the eighth. And the Reds won the game in extra innings when, of all people, relief pitcher Clay Carroll smacked a solo homer off Gibson in the top of the tenth before shaking off a one-out walk in the bottom to end the game and pick up the win.

Survey says: Twenty-five games lifetime in which Gibson has surrendered one or more homers and hit at least one batter in the same game. Duke Snider’s still the only man to get a plunk his next time up after hitting one out. Willie Crawford and Willie Stargell have homered but gone unscathed in at least one plate appearance before getting theirs in the same game. Call it the Willie Asterisk if you like.

1970—Curt Flood refused to report to the Phillies when traded to them for Dick Allen, who saw coming to St. Louis as his overdue liberation following the nightmare of his Phillies seasons. And as Flood prepared his reserve clause challenge, the Cardinals finished fourth in the NL East again.

As for Bob Gibson, who’d win his second of two Cy Young Awards, lead the league with 23 wins (his final 20-game winning season), and lead the league in fielding-independent pitching (your ERA when your defenses are removed from the equation) for the third consecutive and final time . . .

21 April, vs. the Cubs—The Cubs beat Gibson and two relievers, 7-4, dropping seven earned runs on Gibson. With the Cubs taking a 2-1 lead in the bottom of the first (Torre opened the scoring with an RBI single off Cubs starter Bill Hands in the top), Gibson hit Ernie Banks with a pitch with the two runs home already (on an RBI triple and a sacrifice fly) and former Phillie Johnny Callison having just hit a two-out single.

The Cardinals made it 4-2 in the top of the seventh, but in the bottom Billy Williams hit a three-run bomb and Callison hit a two-run shot to send Gibson out of the game.

8 May, vs. the Braves—The Braves won, 8-7, hanging relief pitcher Chuck Taylor with the loss, even though the Cardinals led three times in the game despite of Gibson surrendering seven earned in five and a third.

Gibson’s hit batsman in the game was Atlanta second baseman Felix Millan. In Millan’s next plate appearance, in the bottom of the sixth, he pushed runners to second and third with a ground out right before Aaron hit a three-run homer to tie the game at seven. Gibson surrendered a followup base hit to Rico Carty before he was lifted for Taylor, who surrendered what proved the winning run when Hal King homered with two out in the seventh.

Now it’s 27 lifetime games in which Gibson’s surrendered a bomb and hit a batter. Duke Snider’s still alone for getting a plunk his next time up after hitting one out; the two Willies still hold the only asterisk.

1971—The Cardinals were back in the pennant race this time, finishing seven games behind the NL East-winning Pirates and seven ahead of the third place-tied Cubs and Mets.

21 April, vs. the Giants—Another matchup of Hall of Fame pitchers, Gibson vs. Gaylord Perry, with the Cardinals winning 5-3. McCovey hit a two-run homer in the bottom of the fourth; Gibson plunked the next batter in the lineup, Dick Dietz. Later in the game with the Giants behind 5-2, Ken Henderson homered solo off Gibson with two out.

McCovey faced Gibson twice more in that game, grounding out in the sixth and flying out to end the eighth. Henderson was 0-for-2 with a walk before he homered.

17 July, vs. the Expos—Behind a pitcher named Ernie McAnally, the Expos beat Gibson and the Cardinals 5-3; Gibson surrendered all five runs and two were unearned. Former Dodger Ron Fairly hit a two-run homer right after Rusty Staub’s RBI double in the top of the third; Fairly hit a sacrifice fly his next time up in the fifth, then got a Willie-asterisk plunk when he led off the top of the eighth.

Gibson had one other plunk in the game—hitting former Met pest Ron Hunt to lead off the top of the fifth. Hunt got even by coming all the way around to score on a throwing error off Boots Day’s followup sacrifice bunt attempt. Before that, Hunt grounded out twice; he was replaced by Gary Sutherland at second base in the bottom of the fifth.

30 July, vs. the Phillies—The Cardinals took this one, 4-3, with Gibson going all the way to beat Chris Short, once the Phillies co-ace with Jim Bunning but not the same since a 1969 back injury.

Gibson opened the bottom of the first by hitting leadoff man Denny Doyle with a pitch. One of baseball’s least threatening hitters (sixteen home runs lifetime), Doyle got revenge in the third with a one-out solo homer and hitting a trio of singles in the fifth, seventh, and ninth, the last of those pulling the Phillies to within a run before Gibson ended the game by getting Larry Bowa to ground out.

18 August, vs. the Reds—The Big Red Machine shut out Gibson and the Cardinals, 5-0. The Reds started the scoring in the bottom of the third, when—after Rose walked but was thrown out stealing—future Red Sox World Series hero Bernie Carbo bopped a solo homer.

In the bottom of the fifth, with Carbo due up third in the inning, Gibson hit . . . Rose, who promptly stole second successfully before Carbo struck out. The Reds went on to put four more on the scoreboard that inning, crowned by George Foster’s two-out, two-run triple. Carbo batted twice more in the game, hitting a single and flying out, without once taking a Gibson plunk.

Survey says: 31 games lifetime in which Gibson has surrendered a homer and hit a batter in the same game. Duke Snider still sits alone but add Ron Fairly to the Willie-asterisk group, now numbering a measly three.

1972—The Cardinals slip back to fourth in the NL East this time. Gibson’s season overall is better than his 1971 season, his ERA back below 3.00 and a 19-11 won-lost record.

1972—The Cardinals slip back to fourth in the NL East this time. Gibson’s season overall is better than his 1971 season, his ERA back below 3.00 and a 19-11 won-lost record.

25 April, vs. the Braves—The Braves took this one, 9-3, behind Hall of Famer Phil Niekro. Gibson surrendered six of the nine runs, one unearned.

He opened the bottom of the first by plunking Felix Millan. That’d teach him: after Ralph Garr forced Millan at second, he stole second. After Aaron struck out, though, Carty singled home Garr and Earl Williams hit a two-run homer, before Darrell Evans walked and subsequently scored on a misplayed fly ball to left.

Knucksie hit Lou Brock with one out in the top of the second. After Niekro and Millan flied out to open the bottom of the inning, Garr singled and Aaron smashed a two-run homer.

The rest of Williams’s game included a ground out, an inning-ending pop out, and an RBI single. The rest of Aaron’s game included a fifth-inning leadoff strikeout, then a walk and a run scored in the seventh.

15 May, vs. the Pirates—The Pirates won, 4-1, with both Gibson and Dock Ellis going the distance. Ellis himself tied the game at one in the bottom of the fifth with a run-scoring force out. Clemente finished the day’s scoring with a three-run homer in the bottom of the seventh.

Clemente was 0-for-3 until he teed off and didn’t get to bat again in the game. But two batters after Clemente’s bomb, Gibson plunked Oliver, who’d had a 1-for-2 day until taking that one. In between the bomb and the plunk, Stargell popped out to first base.

That’ll be 33 games for Gibson surrendering a bomb and hitting a batter. Snider still sits alone, and Crawford, Stargell, and Fairly still have the only three Willie asterisks. If that’s enough to give you the willies . . .

1973—Back to a second place finish for the Cardinals, in the season where the Mets started September at rock bottom and ended up winning the weak division before beating the Big Red Machine in a testy League Championship Series and almost winning the World Series in seven games against the Mustache Gang Athletics.

Gibson had a solid season with his 2.77 ERA, though he missed almost all of August and September on the disabled list. Otherwise . . .

20 May, vs. the Expos—Game one of a doubleheader in Montreal, the Expos win, 4-1. Gibson led off the bottom of the second by hitting Mike Jorgensen with a pitch, and Bob Bailey, the next man up, promptly smashed a two-run homer. The rest of Bailey’s game: inning-ending ground out in the third, leadoff single in the sixth, inning-ending fly out in the eighth.

26 June, vs. the Phillies—Also game one of a doubleheader, in Philadelphia, and it was a 10-3 massacre with Gibson responsible for eight runs, all earned, and the carnage only began when he wild-pitched Doyle home while working to Del Unser in the bottom of the first.

With two outs and two on in the bottom of the fifth, Gibson hit Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt with a pitch. Guess he got even with Schmidt for rapping . . . an RBI single his previous time up, making the score 4-2, Phillies at the time. In the sixth, Unser hit a three-run homer to make it 8-3; Gibson was out of the game after that inning.

Make it 35 games for Gibson surrendering a bomb and hitting a batter. Snider’s still alone. Crawford, Stargell, and Fairly still have the Willies.

1974—Gibson’s age begins showing at last thanks to his bothersome knees, despite the Cardinals finishing a game and a half behind the NL East-winning Pirates.

5 April, vs. the Pirates—The Cardinals held on for a 6-5 extra-innings win, and this is the only 1974 game in which Gibson surrenders a homer and hits a batter. With two out in the first, Gibson hit Al Oliver. With two out in the third, Richie Hebner hit a two-run homer.

Hebner flied out in the fifth, then led off the seventh with a solo homer off Gibson. A fly out (Oliver), a base hit (Stargell), and a strikeout (Richie Zisk) later in the seventh, Gibson drilled Dave Parker. Hebner got to hit a leadoff double in the tenth, scoring on Stargell’s single to put the Pirates up 5-4, before RBI singles by Tim McCarver and Ted Sizemore in the bottom got the Cardinals the win.

In 1975, Gibson came to the end of the line as the Cardinals finished tied for third with the Mets in the NL East. He didn’t pitch a single game in 1975 in which he surrendered a home run and hit a batter; he hit four batters all year long.

Thirty-six times in 528 major league games Bob Gibson surrendered at least one home run and hit at least one batter in the same game. He only ever hit one such bombardier the next time the man batted in the game; he hit three such bombardiers not the next time up but in a later plate appearances in games in which they homered first; and he surrendered home runs after hitting batters with pitches in fourteen lifetime games.

He wasn’t just ‘brushing back’ batters—especially those who had hit a donga off him the time before. He was damn well trying to hit them.

And he failed more often than not.

Even if you assume Gibson was good for a brushback pitch either right after a home run or to the same home run hitter the next time up against Gibson, the only hitter ever to get hit by a Gibson pitch the next time up against him was Duke Snider. And the only three hitters ever to get hit by Gibson pitches not immediately but still in later plate appearances in the same games were Willie Crawford, Willie Stargell, and Ron Fairly.

The only thing left to wonder, really, is just what Bob Gibson held against Roy McMillan.

1972—The Cardinals slip back to fourth in the NL East this time. Gibson’s season overall is better than his 1971 season, his ERA back below 3.00 and a 19-11 won-lost record.

1972—The Cardinals slip back to fourth in the NL East this time. Gibson’s season overall is better than his 1971 season, his ERA back below 3.00 and a 19-11 won-lost record.