Not even Mother Nature could rain on Max the Knife’s parade Monday night.

Forget the starters-as-relievers plan that imploded with whatever impostor crawled into Patrick Corbin’s uniform Sunday. Come Monday, the Nationals wanted, needed, and all but demanded one thing.

On a day the Nats were one of four teams facing postseason elimination they needed Max Scherzer to be as close to Max Scherzer as possible. In the worst way possible. In the rain, even.

From the moment after Dodgers third baseman Justin Turner belted a two-out solo homer in the top of the first until he finally ran out of fuel while squirming out of a seventh-inning jam, Scherzer was a little bit more. For six and two-thirds to follow he was Max the Knife.

“It was amazing just playing behind him,” said third baseman Anthony Rendon after the Nats locked down the 6-1 Game Four win. “Max did what Max does.”

Elder Ryan Zimmerman, who wielded the heavy tenderiser in the bottom of the fifth, was a lot more succinct. “That’s the guy,” he said almost deadpan. Except that Zimmerman was also the guy. This was the night the Nats played sweet music from the elders. Above and beyond what they demanded going in.

Scherzer slew the Dodgers with what seemed like a thousand off-speed cuts mixed in with a few hundred speed slices and the Dodgers left unable to decide whether he’d dismantled them or out-thought them. Maybe both at once. Zimmerman was the third among division series teams’ oldest or longest-serving players Monday to do the major non-pitching damage keeping them alive without respirators to play another day.

An hour or so earlier, ancient Yadier Molina tied (with an eighth-inning single) and won (with a sacrifice fly) to get the Cardinals to a fifth game against the Braves. Great job, Yadi. Could the Nats top that? Zimmerman’s electrifying three-run homer answered, “Don’t make us laugh.”

All of a sudden the Dodgers’ stupefying sixth-inning assault in Game Three seemed like little more than a somewhat distant nightmare. Just as swiftly the Dodgers looked like the doddering old men on the field. Their average age is a year younger than the Nats’ but suddenly they looked in need of walkers and wheelchairs.

Scherzer and Zimmerman did their jobs so thoroughly that manager Dave Martinez didn’t even have to think about risking his or his club’s survival with a call into the Nats’ too-well-chronicled arson squad. If he had anything to say about it, the last thing he wanted was anyone not named Sean Doolittle or Daniel Hudson on call.

“I knew I needed to make a full-on start,” said Max the Knife after the game. “I know there’s times in the regular season where you’re not fresh, where you come into a game and you got to conserve where you’re at—try to almost pitch more—and today was one of those days.”

At first it seemed the Nats were trying to conserve . . . who know precisely what. Especially when it didn’t seem as thought they had that many solutions for Dodger starter Rich Hill’s effective enough breaking balls the first two innings. Or, for figuring out ways to avoid loading the bases twice, as they did on Hill and his relief Kenta Maeda in the third, and getting nothing but Rendon’s game-tying sacrifice fly to show for it.

But with that one-all tie holding into the bottom of the fifth, and Julio Urias in relief of Maeda, Trea Turner led off with a bullet single to left and Adam Eaton sacrificed him to second. Rendon singled Turner home to break the tie, Howie Kendrick lined a single to left center, and it looked like the Nats would content themselves with doing things the small ball way.

Then Dodger manager Dave Roberts lifted Urias for Pedro Baez. Zimmerman—the elder into whom enough were ready to stick a fork, though he’d said often enough he’d like to play one more year even as a role player—checked in next. Despite losing the platoon advantage. After he looked at a slider for a strike on the floor of the zone, he turned somewhat crazily on a fastball practically up in his face.

And, he sent it through the outfield crosswinds and onto the green batting eye past the center field fence.

“That’s what you play for, that’s what you work for all season and off season,” said Zimmerman, who hasn’t has as many such moments recently as he’d prefer but who’s still a much loved figure in his clubhouse and among the Nats’ audience. “Stay positive, the guys rallied around me, it’s nice to be back at all.”

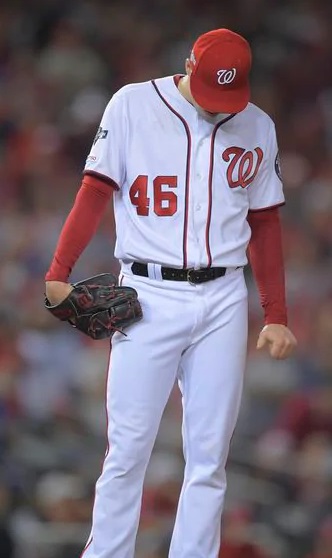

Let the old men be kids again: Zimmerman after his crosswind-splitting three-run bomb.

The Nats went on to tack their sixth run of the night on when Rendon hit another sac fly, this time to the rear end of center field, this time enabling Turner to come home. Greater love hath no Nat than to sacrifice himself twice for the dance. Unless it was Scherzer graduating from his tank next to E to living on pure fumes pitching the top of the seventh.

He got Corey Seager to fly out to right but surrendered a base hit through the right side to rookie Matt Beaty. Rookie Dodger second baseman Gavin Lux wrestled his way to an eight-pitch walk, and rookie catcher Will Smith looked at one strike between four balls for ducks on the pond, but pinch hitter Chris Taylor (for reliever Ross Stripling) threatened to walk the second Dodger run home until Scherzer struck him out swinging on the eighth pitch of the segment.

Then, after scaring the Nats and the Nationals Park crowd audibly with a hard liner down the right field line and foul by about a hair (every known replay showed how close it missed), Joc Pederson grounded one to second base, where late-game fill-in Brian Dozier picked it and threw him out. Launching Scherzer into one of his own patented mania dances into the dugout in triumph.

“My arm is hanging right now,” Max the Knife said after it was all over but the flight back to Los Angeles and a Game Five showdown between Stephen Strasburg and Walker Buehler. “That pushed me all the way to the edge—and then some.” Good thing Doolittle had four outs to deliver and Hudson, two, to close Game Four out with a flourish of their own.

In a game culture so heavily youth-oriented over the past few years Scherzer and Zimmerman must seem anomalous. “We’re a bunch of viejos,” Scherzer told a postgame presser about themselves and their fourteen teammates over the age an earlier generation considered the cutoff for trust. “We’re old guys. Old guys can still do it.”

That wasn’t easy or necessarily guaranteed. Scherzer’s season was compromised by an attack of bursitis and an upper-back rhomboid muscle, forcing him to miss the last of July and most of August. When he returned, after a couple of short but effective enough starts, he almost looked older than his actual 34 years.

He still kept his ERA to 2.92 and still led the Show with a 2.45 fielding-independent pitching rate, but entering the postseason there were legitimate questions about how much he might still actually have left past this year. Like Zimmerman, Scherzer would far rather let himself decide when he’s ready for his baseball sunset.

Max the Knife proved Exhibit A in favour of Martinez’s original starter-as-reliever division series scheme, striking out the side swinging in the eighth in Game Two. And Corbin’s Game Three implosion put the S-A-R idea to bed for the rest of the series, if not the postseason.

Zimmerman is, of course, the one Nat remaining who’s worn their colours since they were reborn in 2005, after long and often painful life as the Montreal Expos. They picked him fourth overall that year; he had an impressive cup of coffee with them down that year’s stretch and stuck but good.

His hope to age gracefully in baseball terms has been thwarted too often by his body telling him where to shove it when he least wants to hear it. He refuses to go gently into that good gray night just yet; he accepts his half-time or part-time status with uncommon grace.

“I really don’t think these are his last games,” Scherzer told the reporters with Zimmerman sitting at his right. “Only you think this is his last games.”

“The last home game [of the regular season], they tried to give me a standing ovation,” Zimmerman said. “I mean, I feel good. I think we’ve got plenty to go.”

“I feel young,” Scherzer said, turning to Zimmerman, “and I’m older than you.”

Scherzer is older than Zimmerman—by two months. But they looked as though they’d told Father Time to step back a hundred paces when they pitched and swung Monday night. Only after the game did they creak like old men.

Zimmerman started only because Martinez wanted to use the platoon advantage against the lefthanded Hill, and he struck out twice. But when he came to the plate as Roberts sent him the righthanded Baez in the fifth, Martinez had a decision: let Zimmerman swing anyway or counter with lefthanded Matt Adams off the bench.

Martinez stayed with Zimmerman. And in that moment Zimmerman became Washington’s King of Swing, leaving Scherzer to settle for being Washington’s King of Sling. Enabling the Nats to live at least one more day. And the way they grunted, growled, and ground Monday night, the Dodgers may yet have a fight on their hands in Los Angeles come Wednesday.

Just don’t expect to see Scherzer out of the pen Wednesday. Even he’s not crazy enough to even think about that scenario. The next time Max the Knife wants to be on the mound it’ll be to pitch for a pennant.