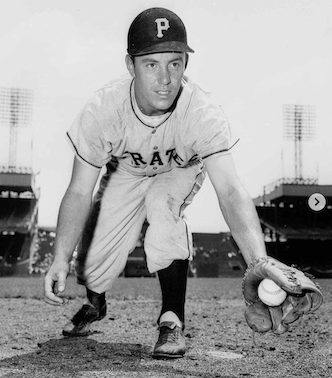

Konnor Griffin, striking for Opening Day at age nineteen.

Opening his poem, “Lines Written in Early Spring,” William Wordsworth lamented,

I heard a thousand blended notes,

While in a grove I sate reclined,

In that sweet mood when pleasant thoughts

Bring sad thoughts to the mind.

That could have been the opening spring lament of baseball fans whose teams are owned by those to whom building and sustaining competitive rosters is an impediment to making or further augmenting fortunes. It’s not impossible to conceive Wordsworth living in America in our day being, say, a Pirates fan.

Except that, for now, early enough in spring training still, the Pirates make some sounds not associated with them too frequently.

A child prodigy, shortstop Konnor Griffin, considered the absolute best of baseball’s youth in waiting, last year’s Minor League Player of the Year, electrifies Pirate fans long bereft of spiritual electricity and non-Pirate fans who savour the excitement young sprouts generate often enough.

Griffin at this writing has slugged his third home run of the spring exhibition season. The co-owner of a baseball laboratory known as Maven Baseball Lab compares him to top-of-the-line performance cars. “You’re looking at a Ferrari. You’re not looking at a little Fiat.” ESPN’s Jeff Passan says Griffin “represents more than a glimmer of hope for a woebegone organization.”

He is the dream of any franchise: top-of-the-scale power and speed, with a nifty glove and a shotgun-blast arm, the kind of work ethic that will make any slacker in his orbit feel like a lout, and a demeanor so polite and accommodating that the words “yes” and “sir” might as well be surgically attached to one another.

Top power and speed? Nifty glove and shotgun blast arm? Work ethic that embarrasses slackers? It sounds rather like Mickey Mantle without the notorious leg trouble and long nights out on the town, at least before the Yankees discovered he might be useless as a shortstop but had center field potential to match his otherworldly power.

Polite? Accommodating? “Yes” and “sir” might as well be surgically grafted? When was the last time we heard a boy shortstop with Griffin’s upside described that way? Cal Ripken, Jr.?

“Can you imagine what John McGraw would say if he saw this kid?” Mantle’s first Yankee manager Casey Stengel said about him in his first Yankee spring. Ripken invited comparisons to Honus Wagner both at the plate, with the glove, and off the field. The Pirates may have to be careful. May.

No, scratch that. At nineteen years old, Griffin so far displays disarming maturity. Either that, or he’s learned some lessons in how not to do media blarney from Bull Durham‘s million-dollar-armed, ten-cent-headed pitching phenom Nuke LaLoosh. LaLoosh was (shall we say) a loose cannon before Crash Davis polished him just enough, including his press cliches.

“I’m happy to be here, and I hope I can help the ball club,” LaLoosh says to the fictitious sports reporter after his late-season call-up to the parent club. “You know, I just want to give it my best shot, and the good Lord willing things will work out. You know, you got to play ’em one day at a time.”

Griffin seems neither that callow nor that scripted. So far.

“I felt really comfortable,” he told reporters after the Sunday game where he delivered spring homer number three. “I’m really working on just being present, taking each game one game at a time. I’m enjoying where I’m at right now, but still got to continue to work and get ready to go tomorrow again.”

A young man on the threshold of his twenties who swung, caught, and threw his way through three minor league levels last year and keeps his head while turning enough others this spring training, thus far, isn’t quite the living, breathing resurrection of a thunderbolt arm attached to an airhead.

Griffin even has room enough to thank the Pirates for letting him be him and letting him let his own serious work of play define him for them. “They’ve done a great job so far allowing me to be free in the minor leagues and be able to move and continue to face challenges,” he tells Passan.

But this spring, I’m really trying not to think about it too much. There’s a lot of noise. I’m just trying to treat it just like I did last spring. I knew I had no chance of just making the big league team. And so every day I was just trying to be a sponge and soak up the advice of these great players who’ve been through it. And I’m trying to do the same thing this year. I know there could be a chance I make the big leagues at some point soon, and that’s great, but I just want to feel ready.

Passan thinks Griffin’s some point soon may come sooner than either he or Pirate fans think. The veteran writer could hardly resist reminding one and all that no teenager has made an Opening Day debut since the year the Berlin Wall came tumbling down and the original World Wide Web debuted. That teenager’s name was Ken Griffey, Jr. No pressure, you understand.

“Goes to church every Sunday, doesn’t cuss, doesn’t do any of that stuff, married at 19,” says the Pirates’ youthful super-pitcher, Paul Skenes. “It’s not common, but nothing about him is common. Everything screams uncommon. And if you want to be uncommon, you want to do uncommon things, it starts with thinking uncommon—and he does that.” Put some Caesar dressing on that word salad if you must, but take it as high praise.

All Griffin has to do is continue living up to it. Even with his well-composed head, that will prove at least as much of a challenge as refusing to let opposing pitchers decompose him or opposing liners and grounders disintegrate him.

He seems aware enough of his game and its encyclopedic history to know that, for every Griffey that arrives on Opening Day still in his teens and goes all the way to the Hall of Fame, there are several hundred who go over, under, sideways, and down, for numerous reasons, and under numerous circumstances. It’s a cinema show for fans—equal parts romance, drama, comedy, horror, psychological thriller, and back—but potential hell for players.

If Griffin keeps the good work up and convince the Pirates he should play on Opening Day, he may or may not have his work cut out for him. The Pirates will face the new-look Mets, who’ve announced Freddy Peralta (import from Milwaukee) as their Opening Day starting pitcher.

The good news for Griffin: Peralta can be prone to the home run. (He surrendered 25 last season.) The bad news: Peralta also struck twice as many out as he walked last year (3.09 K/BB rate) and 10.4 per nine innings. The worse news: Griffin is trying to make a team retooled toward a postseason expectation or three but with ownership known for mistaking monkey wrenches for baseball equipment.

Wrote Wordsworth four verses later:

The budding twigs spread out their fan,To catch the breezy air;And I must think, do all I can,That there was pleasure there.

Yep. Wordsworth among us today just might be a Pirate fan. Or, at least, an empath toward their current most shining prospect.