Mays hitting his 500th career home run, in 1965. “He has gone past me,” Ted Williams would say at his own Hall of Fame induction, after Mays hit number 522, “and he’s pushing, and I say to him, ‘Go get ’em, Willie’.”

Seeing Willie Mays in my boyhood when he was a Giant still in his prime was as transcendent as seeing him in his baseball dotage, as a late-career Met, was heartbreaking. Having Mays at all back in the city where he really made his baseball bones was as much a belated blessing as having him too much less than his best was sorrow. But . . .

“What do you love most about baseball?” asked Joe Posnanski, in The Baseball 100. (He ranked Mays number one.) Then, he answered. “Mays did that. To watch him play, to read the stories about how he played, to look at his glorious statistics, to hear what people say about him is to be reminded why we love this odd and ancient game in the first place.

“Yes, Willie Mays has always made kids feel like grown-ups and grown-ups feel like kids. In the end, isn’t that the whole point of baseball?”

But having Mays say farewell the way he did in Shea Stadium on 25 September 1973, with the Mets still yanking themselves back to take a none-too-strong National League East, brought tears not just of loss but of gratitude. If so few of the greats retire before the game retires them, fewer than that retire with Mays’s soul depth:

I hope that with my farewell tonight, you will understand what I’m going through right now. Something that—I never feel that I would ever quit baseball. But as you know, there always comes a time for someone to get out. And I look at the kids over here [pointing toward his Mets teammates], the way they are playing, and the way they are fighting for themselves, tells me one thing: Willie, say goodbye to America.

America never really said goodbye. Now America must say a reluctant au revoir. Mays left this island earth at 93 Tuesday. “I want to thank you all from the bottom of my broken heart for the unwavering love you have shown him over the years,” said his son, Michael, in a statement. “You have been his life’s blood.”

We’ve been his life’s blood? The younger Mays had it backward. His father was the lifeblood of every objective and appreciative baseball fan of his time. He didn’t have to wear the uniform of the team for which I rooted since their birth (not right away, anyway) to be that for me, in hand with Sandy Koufax, and believe me when I tell you that watching Koufax going mano a mano against Mays was something precious to behold.

(For the record, Mays faced Koufax 122 times and nailed 27 hits. Five were home runs, eight were doubles, one was a triple, for 33 percent extra bases off the Hall of Fame lefthander. Mays also wrung 25 walks out of him while striking out 20 times.)

Before Mays’s Giants and Koufax’s Dodgers high tailed it out of Manhattan and Brooklyn for the west coast, the most bristling debates in New York involved not politics, finance, or rush-hour traffic, but baseball. As in, whom among the three Hall of Fame center fielders patrolling the territory for each team was The Best of the Breed.

I was born in the Bronx and raised there and on Long Island; I heard the debates for years to follow after the Dodgers and the Giants went west. I had skin enough in that game long before Terry Cashman wrote and recorded his charming hit, “Willie, Mickey, and the Duke (Talkin’ Baseball).” Well, now. Let’s look at the trio during their New York baseball lives two ways, for all the seasons they played in New York together. (Snider was a four-year major league veteran by the time Mays and Mantle arrived in 1951.)

First, according to my Real Batting Average metric (total bases + walks + intentional walks + sacrifice flies + hit by pitches, divided by total plate appearances):

| Together In New York | PA | TB | BB | IBB | SF | HBP | RBA |

| Mickey Mantle | 3493 | 1648 | 524 | 34 | 11 | 5 | .636 |

| Willie Mays | 3299 | 1718 | 362 | 70 | 23 | 11 | .662 |

| Duke Snider | 2629 | 1305 | 283 | 42 | 6 | 7 | .625 |

Mays has a 26-point RBA advantage over Mantle and that’s with Mays losing over a season and a half to military service. (Mantle’s osteomyelitic legs kept him out of military service; Snider served in the Navy before his major league days began.) Mays also landed 70 more total bases and was handed 36 more intentional walks.

Mantle may have been a powerful switch hitter, but just from one side of the plate Mays outperformed him while they shared New York even with precious lost major league time between ages 21-23. Mantle also had a .756 stolen base percentage to Mays’s .738, but a) Mantle’s already compromised legs kept him from trying more often; and, b) Mays led his league in thefts twice during the period under review. (Snider? Even a hobbled Mantle left him behind: for their shared New York years, his stolen base percentage was .586.)

Sometimes Mantle gets the props as the best of the trio purely because his Yankees were far better teams than the others’. Actually, Snider’s Dodgers were almost as good as Mantle’s Yankees. It was no more Snider’s fault that his Dodgers couldn’t get over those Yankee humps until 1955 than it was Mantle’s sole doing that his Yankees won seven pennants and five World Series (three consecutively) while they shared the Big Apple.

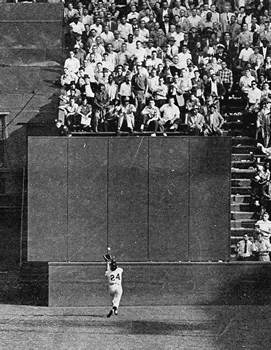

And it was hardly Mays’s fault that his Giants won a mere two pennants in the same shared span, even if Mays’s Giants got squashed by the Yankees in five in the 1951 Series but swept the far better Indians in the 1954 Series. You may have heard of a little play known as The Catch from Game One of that Series, happening when it seemed the Indians had a shot at taking the opener. (Mays would play on two more pennant winners, too, the 1962 Giants—who beat the Dodgers in another memorable pennant playoff—and the 1973 Mets.)

“The Catch,” of course—460+ feet from home plate in the ancient Polo Grounds.

“That really wasn’t that great of a catch,” harrumphed curmudgeonly Indians pitcher Bob Feller, nearing the end of his own Hall of Fame career. What made him think not? “As soon as it was hit, everyone on our bench knew that he was going to catch it . . . because he is Willie Mays.” (But did they know Mays would also keep Hall of Famer Larry Doby from scoring with an equally staggering throw in to the infield off The Catch?)

Which brings me to the titanic triumvirate in center field. We’re going to look at them according to total zone runs, the number of runs their play in center field turned out above or below their leagues’ averages. Baseball-Reference begins measuring total zone runs with the 1953 season, so we’ll have five solid Big Apple seasons to review for each of the trio:

Willie Mays: +45.

Mickey Mantle: +22.

Duke Snider: +25.

Once again you see where Mantle’s physical health issues got in his way despite his supernatural talent and skill. But it might not have mattered. Mays and Mantle both played in unconscionably deep home center fields before the Giants and the Dodgers left the Apple for 1958. You can fantasise all you like how many runs Mantle might have prevented on good legs, but if you guess that he might have proven just about even you’re making a solid guess.

“Willie Mays going after a fly ball was cotton candy and a carousel and fireworks and a big band playing all at once,” Posnanski wrote. “His athletic genius was in how every movement expressed sheer delight.”

When Mays got to San Francisco, he and Mantle continued their top of the line play. When he got to Los Angeles, Snider had two decent seasons followed by a decline phase that actually took him back to New York for a round with the early Mets before finishing his career in 1964 as . . . a Giant, of all things.

Mantle managed to remain Mantle through the end of 1964. Mays managed to remain Mays through at least 1971. Even if his home run power had dissipated somewhat in the previous four seasons, he spent 1971—at age 40—leading the National League in walks and on-base percentage. Mantle’s body took him out at last at age 36; Mays’s, at age 42; Snider’s, at age 37.

And here is how the trio finished career-wise. First, how they sit among the Hall of Fame center fielders whose careers covered the post-World War II/post-integration/night-ball era, according to RBA:

| Center Field | PA | TB | BB | IBB | SF | HBP | RBA |

| Mickey Mantle | 9907 | 4511 | 1733 | 148 | 47 | 13 | .651 |

| Willie Mays | 12496 | 6066 | 1464 | 214 | 91 | 44 | .631 |

| Ken Griffey, Jr. | 11304 | 5271 | 1312 | 246 | 102 | 81 | .620 |

| Duke Snider | 8237 | 3865 | 971 | 154 | 54 | 21 | .615 |

| Larry Doby | 6299 | 2621 | 871 | 60 | 39 | 38 | .576 |

| Andre Dawson | 10769 | 4787 | 589 | 143 | 118 | 111 | .534 |

| Kirby Puckett | 7831 | 3453 | 450 | 85 | 58 | 56 | .524 |

| Richie Ashburn | 9736 | 3196 | 1198 | 40 | 30 | 43 | .463 |

| HOF CF AVG | .588 | ||||||

But now, how they sit among center fielders for run prevention above their league averages, showing the top ten:

Andruw Jones +230

Willie Mays +176

Paul Blair +171

Jimmy Piersall +128

Kenny Lofton +117

Devon White +112

Carlos Beltrán +104

Willie Davis +103

Curt Flood +99

Garry Maddox +98

Thanks to his leg and hip issues, Mantle finished his career at -10. Snider finished his at -7; his late career was compromised by knee, back, and arm injuries. (Richie Ashburn, their great Hall of Fame contemporary, finished his career +39.) Two such talented center fielderss who’d had excellent throwing arms and range deserved far better than such physical betrayals.

Mays stood alone as the complete, long-enough uncompromised, all-around package. He was blessed with a body that wasn’t in a big hurry to betray him, but no blessing means a thing if you don’t take it forward. Good luck stopping Mays from doing so. Should-be Hall of Famer Dick Allen once advised Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt to play the game as though he were still the kid who’d gladly skip supper to play ball. Mays played the game precisely that way until age began to say “not so fast,” after all.

“The greats don’t always go gently into that good gray night when they can no longer play the games that made their names,” I wrote when Mays turned 90.

This son of an Alabama industrial league ballplayer fought a small war in his soul when his age insisted he was no longer able to play the game he loved so dearly at the level on which he’d played it for so many years. Some said he’d become sullen, moody, dismissive in the clubhouse. Some resented him, others felt for him, still others mourned.

. . . When he smiled as a Met, you still saw him in his youth, you didn’t see the manchild who was yanked rudely into manhood by a San Francisco that shocked him with skepticism as a New York import rather than a hero of their own. By a San Francisco that also shocked him, for all its reputation otherwise, when his bid to buy a home with his first wife was obstructed long enough by the sting of neighbourhood racism.

Mays taken for a drive around PacBell Park in a 1956 Oldsmobile to celebrate his 90th birthday. San Francisco came to love him as New York did, but not without growing pains.

After his first marriage ended in divorce and in his son living across country with his mother, Mays dated Mae Louise Allen for about a decade before marrying her after the 1971 season. His happiness there was compromised by her premature Alzheimer’s diagnosis; his caring for her until her death in 2013 is the stuff of true love stories.

A welcome presence at the Hall of Fame’s induction ceremonies following his own in 1979 and at various Giants events (and numerous home games) in the years that followed, Mays wouldn’t be able to attend this year’s Field of Dreams game at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field, the field where he first played with the Birmingham Black Barons of the old Negro American League.

“I’d like to be there, but I don’t move as well as I used to,” he said in a statement on Monday. “So I’m going to watch from my home. But it will be good to see that. I’m glad that the Giants, Cardinals and MLB are doing this, letting everyone get to see pro ball at Rickwood Field. Good to remind people of all the great ball that has been played there, and all the players. All these years and it is still here. So am I. How about that?” A day later, sadly, he was gone.

Mays never apologised for making the game look fun with his fabled basket catches in front of his belt, his winging turns running the bases as his deliberately oversized hat flew off, his high-pitched voice sounding like a kid getting to play yet another inning.

“That’s what his idea was,” said one-time Giants relief pitcher Stu Miller, “to please the crowd.”

“I’m not sure what the hell charisma is,” said Ted Kluszewski, the musclebound Reds first baseman of the 1950s, “but I get the feeling it’s Willie Mays.”

“The only thing Willie Mays could not do on a baseball diamond,” Posnanski wrote, “was stay young forever.”

May his entry into the Elysian Fields, where it’s Willie, Mickey, and the Duke once again, and especially his reunion with his beloved Mae, have been as joyous for him as the way he played the game was joyous to us for as long as we were honoured to see him play.