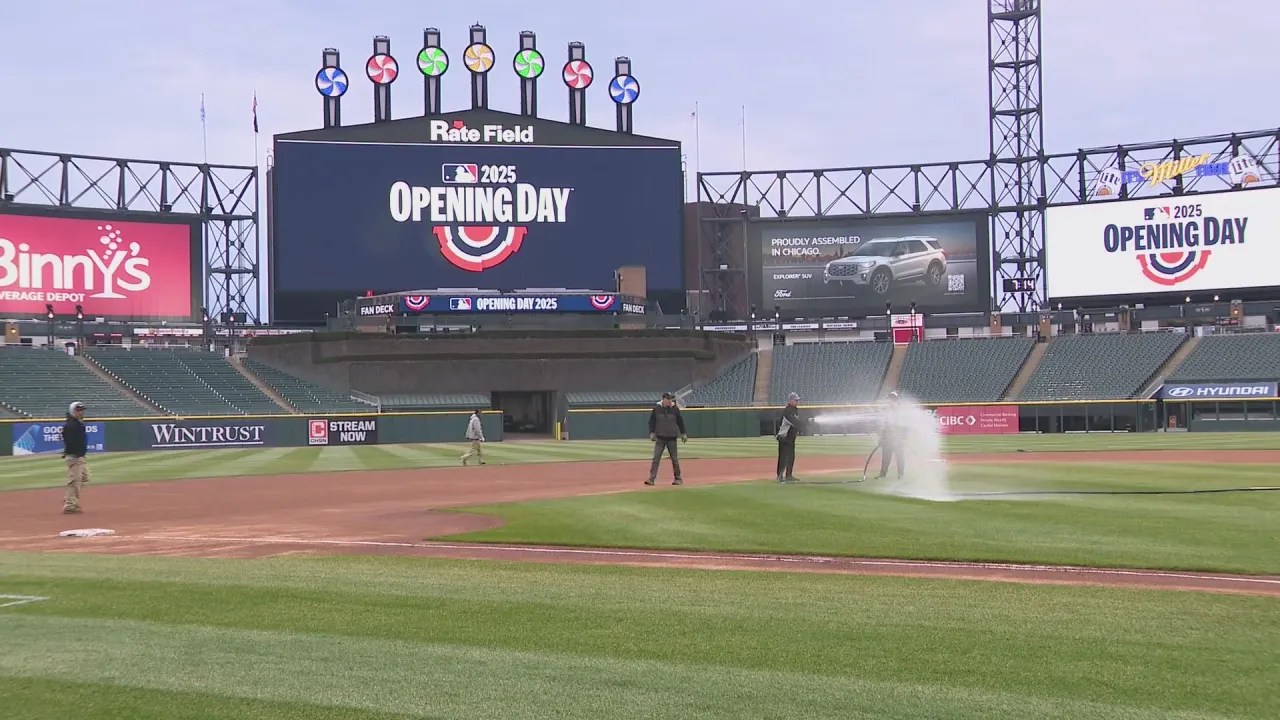

The grounds crew conditions Rate Field in Chicago for Opening Day. Little did they or those fans who did show up know the White Sox would open with—stop the presses! (as we’d have said in ancient times)—a win.

Opening Day is many things. Boring is never one of them. This year’s Opening Day certainly offered further evidence, including but not limited to . . .

Ice, Ice, Shohei Dept.—First, Ice Cube drove the World Series trophy onto the pre-game Dodger Stadium field. Then, 1988 World Series hero Kirk Gibson threw a ceremonial first pitch to 2024 World Series hero Freddie Freeman. Then, Shohei Ohtani finally ironed up in the seventh and hit one out for the badly-needed insurance, enabling the Dodgers to beat the Tigers, 5-4.

That left the Dodgers 3-0 after MLB’s full Opening Day, and one after they swept the Cubs in the Japan Series. I did hear more than a few “Break up the Dodgers” hollers, didn’t I?

This Time They Spelt It Right Dept.—“Traitor,” that is, when Bryce Harper and his Phillies opened against Harper’s former Nationals in Washington . . . and Harper said welcome to 2025 by stuffing the boo birds’ mouths shut with a blast over the right center field fence in the top of the seventh. That kicked the Phillies into overcoming a 1-0 deficit toward winning, 7-3.

That launch tied Harper for the most Opening Day home runs among active players, with six, but this was the first time he did it in Phillies fatigues.

“I love coming in here and playing in this stadium,” said Harper postgame. “I’ve got a lot of great memories in here, as well. Everywhere I go, it’s exactly like this. Some places are louder than others. It’s all the same.” Except that he left Washington a prodigious but lowballed boy to become man of the Phillies’ house since he signed with them for keeps in 2019.

I Can Get Started Dept.: Tyler O’Neill Display—One of the players Harper’s sixth Opening Day blast tied is Orioles outfielder Tyler O’Neill. That’s where the similarities end between them, for now—in the top of the third against the Jays, O’Neill hammered Jose Berrios’s sinker for a home run to make it six straight Opening Days he’s cleared the fences.

O’Neill hit 31 homers and produced an .847 OPS for last year’s Red Sox, before signing with the Orioles this winter as a free agent.

I Can Get Started Dept.: Paul Skenes Display—The indispensable Sarah Langs pointed out that Pirates sophomore Paul Skenes—fresh off his Rookie of the Year season—became the fastest number one draft pick to get his first Opening Day start yet, getting it just two years after he went number one. That beat Mike Moore (1981 daft; 1984 Opening Day) and Stephen Strasburg (2009 draft; 2012 Opening Day).

The bad news: Skenes had a respectable outing on Thursday, only two earned runs against him, but the Marlins managed to turn a 4-1 deficit into a 5-4 win when their left fielder Kyle Stowers walked it off with an RBI single in the bottom of the ninth.

I Can Get Started Dept.: Spencer Torkelson Display—My baseball analysis/historical crush Jessica Brand informs that Spencer Torkelson, Tiger extraordinaire, is the first since 1901 to draw four walks and hit one out in his team’s first regular season game.

Fallen Angels Dept.—Things aren’t bad enough with the Angels as they are? They not only had to lose on Opening Day to last year’s major league worst, and in the White Sox’s playpen. They needed infielder Nicky Lopez to take the mound in the eighth to land the final out of the inning—after the White Sox dropped a five spot Ryan Johnson in his Angels debut. Lopez walked White Sox catcher Korey Lee but got shortstop Jacob Amaya to fly out for the side.

Jessica Brand also reminded one and all that the last time any team reached for a position player to pitch when behind on Opening Day was in 2017, when the Padres called upon Christian Bethancourt with the Dodgers blowing them out.

South Side Reality Checks Cashed Dept.—The White Sox didn’t exactly fill Rate Field on Thursday. (I’m sure I’m not the only one noticing the Freudian side of “Guaranteed” removed from the name.) But those who did attend weren’t going to let little things like a 121-loss 2024 or nothing much done to improve the team this winter stop them.

“It’s delusion that feeds me,” said a fan named JeanneMarie Mandley to The Athletic‘s Sam Blum. “I don’t care . . . I know we suck. I’m not stupid.”

We’re guessing that a hearty enough share of White Sox fans think Opening Day’s 8-1 win over the Angels was a) an aberration; b) a magic trick; c) a figment of their imaginations; or, d) all the above.

Well, That Took Long Enough Dept.—What do Mickey Cochrane, Gabby Hartnett, Ernie Lombardi, Yogi Berra, Roy Campanella, Johnny Bench, Carlton Fisk, Gary Carter, Ted Simmons, and Ivan Rodriguez have in common other than Hall of Fame plaques?

The answer: They never hit leadoff homers on Opening Day in their major league lives. But Yankee catcher Austin Wells did it, this year, on Thursday, sending a 2-0 service from Brewers starter Freddy Peralta into the right field seats to open the way to a 4-2 Yankee win.

“Why doesn’t it make sense?” asked Yankee manager Aaron Boone postgame. Then, he answered: “Other than he’s a catcher and he’s not fast, although actually he runs pretty well for a catcher . . . I think he’s gonna control the strike zone and get on base, too, and he’s very early in his career. I think when we look up, he’s gonna be an on-base guy that hits for some power.”

We’ll see soon enough, skipper.

Don’t Put a Lid On It Dept.—The umps admitted postgame that they missed completely a flagrant rules violation by Yankee center fielder Trent Grisham in the ninth Come to think of it, it seems both the Brewers and the Yankees missed it, even if Brewers fans didn’t.

With a man on, Devin Williams on the mound for the Yankees, and Isaac Collins at the plate for the Brewers, Collins ripped one into the right centerfield gap. Grisham ran it down, removed his hat, and used the hat to knock the ball down after it caromed off the fence, the better to keep the ball from going away from him.

With one and all missing the rules violation, it left Collins on second with a double and the Brewers with second and third—instead of Collins on third with a ground-rule triple and the run scoring. Had anyone seen Grisham’s move and demanded a review, it might have meant just that and, possibly, the Brewers winning the game in the end. Possibly.

Just Juan Game Dept.—Juan Soto’s regular-season Mets debut was respectable: 1-for-3 with two walks and one strikeout. But he didn’t get to score or drive home a run. The Mets, who still have baseball’s best Opening Day winning percentage, lost to the Astros, 3-1, in Houston.

The only serious problem with Soto’s punchout was Astros closer Josh Hader doing it to him with two on in the ninth. Now, try to remember this about that ninth:

* The Mets entered trailing 3-0.

* Hader surrendered two singles and a bases-loading walk to open.

* Then, he surrendered a sacrifice fly by Francisco Lindor to spoil the shutout.

* Hader fell in the hole 3-0 to Soto first.

* Then, he got Soto to look at a strike, foul one off, then swing and miss on a low slider.

That’s how Hader earned an Opening Day save and a 9.00 season-opening ERA. That’s further evidence—and, from the Craig Kimbrel School of Saviourship, of course—that the save is one of the least useful statistics in baseball.

Or: That kind of save is like handing the keys to the city to the arsonist who set the fire from which he rescued all the occupants in the first place.

Blind Justice Dept.—Umpire Auditor reports that Opening Day umpires blew 186 calls. That would average out to about 2.6 blown calls per umpire, I think. Just saying.

Just Wrong Dept.—Is it me, or—aside from the pleasure of only one true blowout (the Orioles flattening the Jays by a ten-run margin)—were there four interleague games on Opening Day?

That’s just plain wrong. It may be an exercise in futility to argue against regular-season interleague play anymore. But the least baseball’s government can do it draw up and enforce a mandate that no interleague games shall be scheduled for Opening Day again. Ever.