So what is with A’s owner John Fisher suddenly opening his purse?

Dave Roberts supports a players’ salary cap and a salary floor. Clayton Kershaw probably thinks his now-former manager could use a little extra enlightenment. It would have made for some lively discussions in the Dodger clubhouse if Kershaw hadn’t retired after the World Series.

“You know what? I’m all right with (a salary cap),” Roberts told Amazon Prime’s Good Sports a month ago. “I think the NBA has done a nice job of revenue sharing with the players and the owners. But if you’re going to kind of suppress spending at the top, I think that you got to raise the floor to make those bottom-feeders spend money too.”

Kershaw picked a slightly showier place to say he thinks the owners bleating for salary caps are talking through their scalps, actor Rob Lowe’s Literally! podcast. But it ain’t the venue, it’s the verdict. “I don’t understand some of the ownerships’ arguments with this stuff,” the future Hall of Fame lefthander began near December’s end.

Because there’s probably hundreds of multi-billionaires that would love to own a professional baseball team. I bet we could get a list of 100 guys right now that are uber-wealthy, that would love to run a baseball team . . . It might not make the money you would want it to make, but over time it’s just like a stock. It’s going to continue to appreciate.

It’s just like anything else. [The Dodgers are now] worth 3x of what it was . . . I don’t really get that part of it, of the owners pinching pennies.

Grammar aside, Kershaw has the amplifier of Roberts’s second point. But what he doesn’t quite get is that the penny-pinchers have one view of baseball. They think, and they have a commissioner who behaves accordingly, that the good of the game is nothing more than making money for themselves.

My Internet Baseball Writers Association of America newsletter colleague Bill Pruden says responsible baseball ownership begins with a full commitment to fielding a competitive team, but you don’t have to look fast to see that’s not exactly every team’s aspiration. “The A’s and the Pirates immediately come to mind,” he continues, “when one thinks of teams that have, for years, offered little evidence of a real commitment to winning.”

It depends upon what your definition of “winning” is.

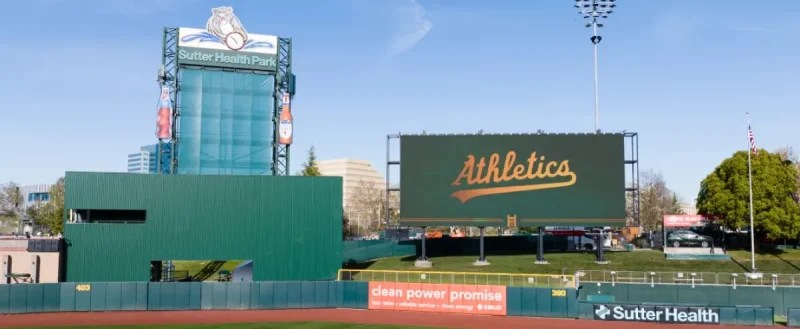

For years, A’s owner John Fisher wanted nothing more than to dump Oakland like an inconvenient wife. He let his A’s shrink to compost but failed to strong-arm Oakland and its home county into handing them a new home almost entirely on the house. He finished what was started long enough ago and let the Coliseum and his team finish becoming compost. He said it was the fans’ fault for not wanting to watch scrap heap baseball.

Then Las Vegas’s mouse-like political (lack of) class signed off on $380 million tax dollars with no public hearings or votes toward building the A’s a garish new playpen on the Strip. The owners rubber stamped Fisher’s betrayal while agreeing to waive the normal $1 billion relocation fee.

Fisher got off the way wealthy husbands only dream of getting off when dumping their aging wives for younger mates. While playing in Sacramento’s minor league playpen awaiting the finish of their glass house, we wonder reasonably whether Las Vegas bought the proverbial pig in the proverbial poke.

But lo! As Buffalo Springfield’s Stephen Stills once wrote and sang, there’s something happening here, and what it is ain’t exactly clear. Or is it? All of a sudden, the A’s are spending. In the past year, Fisher’s purse has opened wide and said, “Aaahhhhhhhhh.” Sort of.

* The A’s extended right fielder Lawrence Butler with seven years at $65.5 million.

* They extended designated hitter/outfielder Brent Rooker with five years at $60 million.

* Most recently, they extended left fielder Tyler Soderstrom to seven years at $86 million, with an eighth-year team option that includes escalators which could hike the value as high as $131 million, according to The Athletic‘s Devon Henderson and Will Sammon. It’s the largest guaranteed deal in the history of the A’s.

No, those aren’t exactly the kind of glandular long-term deals bestowed upon the Shohei Ohtanis, Bryce Harpers, and Mike Trouts of the game. Bo Bichette could land a more valuable deal than those three combined. And optimists think the A’s are prepping for 2028, when their new playpen is supposed to open where the Tropicana Hotel and Resort used to stand.

But $256.5 million is money not heretofore seen flying out from the A’s piggy banks, even if it’s less than a) some teams’ entire payrolls, and b) a third the full value of Ohtani’s ten-year contract. And it might be hard to remember Fisher speaking the way he did to another Athletic writer, Evan Drellich, earlier this offseason.

“At the end of the day,” Fisher told Drellich, “our goal is to put the greatest team on the field that we can and payroll is an important part of that. But our [front office has] demonstrated over decades now that they can see things in players that other teams don’t see . . . We’re going to sign our guys to longer-term deals, as well as sign free agents who can make our team better.”

Until they aren’t?

Those three extensions, wrote Yahoo! Sports’s Mark Powell, were “a stark reminder that [Fisher] always had the money, but chose not to spend it.” Tell the abandoned wife named Oakland what she didn’t know.

Real cynics think you can tell most baseball owners lying when you see their lips move. The current collective bargaining agreement’s coming finish at the end of the 2026 season already has “salary cap” on those lips, with “salary floor” seeming to be a sotto voce side or afterthought.

Maybe few to none among those owners might dare to ponder Kershaw’s thought about wealthy men and women willing to buy in and actually invest in building competitive teams. They might sooner respond to him, now that he’s retired with only his Hall of Fame election ahead of him so far, “Beat it, buster.”

Ask Oakland whether Fisher’s words are his bonds. They’re liable to demand polygraph proof.

First published at Sports Central.