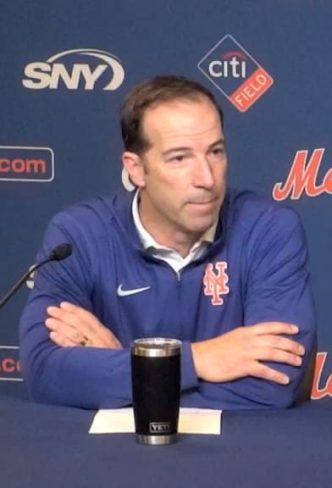

Billy Eppler leaves the Mets to hunt a new GM, while MLB investigates his use/misuse/abuse of the so-called phantom injured list.

Something is further amiss in the milieu of the Mets than just the sunken season that compelled manager Buck Showalter’s scapegoating. It may not be limited to the Mets alone, but with general manager Billy Eppler resigning—possibly before he, too, might have been shown the door—it’s the Mets drawing the headlines on it.

First, it came forth that Eppler all but strong-armed Showalter into continuing to write Daniel Vogelbach’s name into the lineup, against just about every piece of evidence saying Vogelbach didn’t truly belong there. Then, it came forth that Eppler was under baseball government investigation over what’s known as the phantom injured list.

Even with the medical advances of this century, it’s bad enough that (you guessed it) baseball medicine could still be tried by jury for malpractise. The phantom injured list—basically, placing underperforming players on it to keep them out of the lineup, while still paying them and granting their major league service time, though possibly denying them certain incentive-based chances—could be called another kind of malpractise.

That would be the kind that calls honest competition into further question that such things as tanking have it already. The kind that compels some baseball people—former Phillies manager Joe Girardi, notoriously enough—to admit they’re not always forthcoming about real injuries the better to keep valuable intelligence out of opposition sights. Never mind that teams can usually tell when the other guys have a likely wounded warrior.

The Mets had 28 real IL placements in 2023. This didn’t even make the Mets the Show’s worst such infirmary roll: the Giants, who dumped manager Gabe Kapler for being unable to maneuver a dubious roster built by president of baseball operations Farhan Zaidi, had 46 IL members. Right ahead of the Reds’ 45 and the Angels’ 42.

By contrast, the healthiest reported 2023 teams were the postseason-reaching Astros (14), the postseason-missing Guardians (17), the postseason-missing Mariners (18), and the postseason-reaching Diamondbacks (also 18).

Teams are supposed to provide medical documentation and approval when they place players on the injured list. The New York Post broke the news that, when MLB investigators informed the Mets that Eppler was being probed over the phantom IL, Eppler elected to resign rather than “potentially become a distraction” as new PBO David Stearns settles into his new job.

“Stashing healthy players on the IL can aid a team competitively,” the Post said, in an article under the joint bylines of Mike Puma, Joel Sherman, Jon Heyman, and Mark W. Sanchez. “Designating healthy players as injured can enable clubs to keep those players under team control rather than risk losing them to other organizations.”

A day before that story broke, Puma reported that Showalter and Eppler clashed over Vogelbach. Showalter likes to use the DH slot as breathers for his position players but also didn’t like Vogelbach’s skill set limits. None of which seemed to matter to Eppler, who continued insisting that the lefthand-swinging Vogelbach remain the DH against righthanded pitching.

It’s one thing to allow a less than perfect physical specimen a place in the lineup at all, but it’s something else to let him stay there if he can’t deliver. Physically, Vogelbach can be described politely as making Babe Ruth resemble Mike Schmidt. His most apparent skill set, his on-base ability, shown well after the Mets acquired him from the Pirates before 2022’s trade deadline, disappeared drastically enough amidst the 2023 Mets’ dissipation.

But Vogelbach lacked power and didn’t hit consistently enough with or without power to convince Showalter he belonged in the Mets’ lineup, no matter how gifted he is at working out walks. His bulk also made him less than mobile enough that playing him at first base or elsewhere could have been considered giving aid and comfort to the opposing lineup.

Fair disclosure: At 6’4″, I once packed 325 pounds. I’ve since lost in the neighbourhood of fifty pounds, striking to return my weight to 225. I empathise with Vogelbach in that regard. But I haven’t played baseball since age 15, when I discovered the hard way I wasn’t any kind of good at it anymore.* And I’m not the guy a GM forced a manager to put in the lineup.

At points in the season’s first half, where the Mets’ more formidable plate presences struggled, Vogelbach’s presence in the lineup looked even more suspicious. There were thoughts public and private that the Mets might move Vogelbach at the 2023 trade deadline, but Puma says when the move didn’t happen Showalter began “questioning openly” why Vogelbach was still a Met.

“Not only was Vogelbach still on the team,” Puma wrote, “but (a) source indicated the manager was told by Eppler to keep him in the starting lineup.” For what purpose? For Eppler to save face over dealing for Vogelbach in the first place?

Marry that to MLB investigating Eppler’s use, misuse, or abuse of the phantom IL, and maybe, just maybe, you have a prospective case of Eppler resigning before Stearns—who’d first said he looked forward to working with him—might be forced to throw him out on his none-too-ample derriere.

Just what the Mets didn’t need now. They hired Eppler in the first place after interim GM Zack Scott was charged with DUI. Scott replaced Jared Porter, after Porter was exposed as having sent sexually explicit text messages to a female reporter. The Mets have to be hoping Eppler’s eventual successor comes at minimum and remains scandal free.

That may prove child’s play compared to the issue that finally compelled Eppler to show himself the door out. It will not do, either, for anyone to confine their curiosity about phantom IL use and abuse to trying to determine who blew the whistle on Eppler. Maybe it’s time to look at all teams and the phantom IL, not the Mets alone.

Maybe it’s long past time that baseball’s entire medical culture was given a full and proper investigation. For the sake of player health, and for the sake of honest competition. And in that order.

—————————————————————————————————-

* At 15, I discovered I couldn’t hit fair unless the foul line ran perpendicular to the back point of home plate. I’ve had long enough legs but you need more than that to run. Even if I could hit one fair, it would have taken me longer than Bartolo Colon to run the bases if I hit one out. Without hitting one out, I could have been the guy who’d get thrown out at first from the bullpen.