A spent champagne bottle placed on home plate after the Yankees won a trip to the ALCS Tuesday night. The Yankees had to celebrate their win in a hurry—they open against the Astros Wednesday night.

The good news is, Year One of Comissioner Rube Golberg’s triple-wild-cards postseason experiment isn’t going to have an all also-ran World Series, after all. It still yielded a pair of division-winning teams getting to tangle in the American League Championship Series.

The bad news is, those two division winners are still the Yankees and the Astros, after the Yankees sent the AL Central-winning Guardians home for the winter with a 5-1 win Tuesday that wasn’t exactly an overwhelming smothering.

What it was, though, was the game for which the Guardians shot themselves in the proverbial foot. Specifically, two Guardians, one of whom is old enough to know better and the other of whom needs a definitive attitude adjustment.

Guardians manager Terry Francona has more World Series rings this century (two) than Yankees manager Aaron Boone (none). Francona is considered by most observers to be one of the game’s smartest managers who’s made extremely few mistakes and learned from one and all; Boone is one of those skippers about whom second-guessing is close enough to a daily sport in its own right.

But when push came to absolute shove for rain-postponed AL division series Game Five, Boone proved willing to roll the dice Francona finally wasn’t.

After Gerrit Cole held the Guards off with a magnificent Game Four performance Sunday but the rain pushed Game Five from Monday to Tuesday, Boone was more than willing to throw his original Game Five plan aside—Jameson Tallion starting and going far as he could to spell the beleaguered Yankee bullpen—and let Nestor Cortes pitch on three days’ rest for the first time in his major league life.

Francona wouldn’t even think about changing his original Game Five plan, opening with his number-four starter Aaron Civale, who hadn’t even seen any action this postseason until Tuesday, then reaching for his bullpen at the first sign of real trouble. He wasn’t willing to let his ace Shane Bieber go on three days’ rest for the first time in his major league life.

Mother Nature actually handed Francona one of the biggest breaks of his life when she pushed Game Five back a day. Either he missed the call or forgot to check his voicemail. “I’ve never done it,” said Bieber postgame Tuesday, about going on three days rest. “But could I have? Sure.”

“It’s not because he can’t pitch,” said Francona after Game Five. “It’s just he’s been through a lot. You know, he had [a shoulder injury in 2021] and he’s had a remarkable year, but it’s not been probably as easy as he’s made it look.”

It might have been a lot easier on the Guardians if Francona handed his ace the chance to try it, with reinforcements ready to ride in after maybe three, four innings. Even year-old-plus shoulder injuries deserve appropriate consideration, of course. But Bieber surrendered a mere two runs in five-and-two-thirds Game Two innings. Francona’s hesitation when handed the chance helped cost him a shot at another AL pennant.

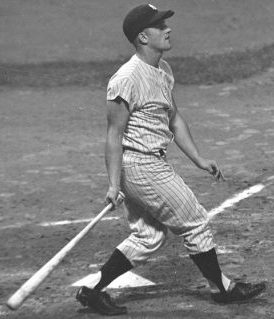

Civale didn’t have it from the outset. He had as much control as a fish on the line jerking into death out of the water. Giancarlo Stanton slammed an exclamation point upon it when he slammed a hanging cutter the other way into the right field seats with two aboard and one out.

The Guards’ pen did surrender two more runs in the game, including Aaron Judge’s opposite field launch the next inning. But they spread those runs over eight and two-thirds innings’ relief while otherwise keeping the Yankees reasonably behaved. They gave the Guards every possible foot of room to come back and win it.

That was more than anyone could say for Josh Naylor. The Guards’ designated hitter had already raised temperatures among enough Yankees and around a little more than half of social media, when his Game Four home run off Cole resulted in him running the bases with his arms in a rock-the-baby position and motion.

Naylor intends the gesture to mean that if he hits you for a long ball he considers you his “son” in that moment. It wasn’t anything new for him or for those pitchers surrendering the 20 bombs he hit on the regular season. And Sunday’s blast was the third time Naylor has taken Cole into the seats in his major league life. He was entitled to a few bragging rights.

Cole himself thought the bit was “cute” and “a little funny.” He wasn’t half as offended as that half-plus of social media demanding Naylor’s head meet a well-placed fastball as soon as possible. Yesterday, if possible. The Yankees found the far better way to get even in Game Five than turning Naylor’s brains into tapioca pudding.

“We got our revenge,” Yankee shortstop Gleyber Torres all but crowed postgame. Torres even did a little rocking of the baby himself in the top of the ninth, after he stepped on second to secure the game-ending force out. “We’re happy to beat those guys,” he continued. “Now they can watch on TV the next series for us. It’s nothing personal. Just a little thing about revenge.”

Naylor was also serenaded mercilessly by the Yankee Stadium crowd chanting “Who’s your daddy?” louder with each plate appearance. Every time he returned to the Guards’ dugout fans in the seats behind the dugout trolled him with their own rock-the-baby moves. And his most immediate postgame thought Tuesday was how wonderful it was that he’d gotten that far into their heads.

Some say it was Naylor being a good sport about it. Others might think he was consumed more with getting into the crowd’s heads than he was in getting back into the Yankees’ heads. The evidence: He went 0-for-4 including once with a man in scoring position Tuesday.

Oh, well. “That was awesome,” he said postgame of the Yankee Stadium chanting. “That was so sick. That was honestly like a dream come true as a kid—playing in an environment like this where they’ve got diehard fans, it’s cool. The fact I got that going through the whole stadium, that was sick.”

Rock and troll: Yankee fans letting Josh Naylor have it on an 0-for-4 ALDS Game Five night.

Did it cross his mind once that his team being bumped home for the winter a little early was a little more sick, as in ill, as in not exactly the way they planned it? If it did, you wouldn’t have known it by the way he continued his exegesis. “If anything, it kind of motivates me,” he began.

It’s fun to kind of play under pressure. It’s fun to play when everyone’s against you and when the world’s against you. It’s extremely fun.

That’s why you play this game at the highest level or try to get to the highest level: to play against opponents like the Yankees or against the Astros or whoever the case is. They all have great fanbases and they all want their home team to win, and it’s cool to kind of play in that type of spotlight and in that pressure.

Wouldn’t it have been extremely more fun if the Guardians had won? Did Naylor clown himself out of being able to play up in that spotlight and its pressure this time? Those are questions for which Cleveland would love proper answers.

So is the question of how and why the Guards didn’t ask for a fourth-inning review that might have helped get Cortes out of their hair sooner than later, after a third inning that exemplified the Guards’ hunt-peck-pester-prod limits.

They went from first and second and one out in the top of the third—one of the hits hitting the grass when Yankee shortstop Oswaldo Cabrera collided with left fielder Aaron Hicks, resulting in a knee injury taking Hicks out of the rest of the postseason—to the bases loaded and one out after Guards shortstop Amed Rosario wrung Cortes for a four-pitch walk. They got their only run of the game when Jose Ramírez lofted a deep sacrifice fly to center.

Now, with two outs in the top of the fourth, Andres Giménez whacked a high bouncer up to Yankee first baseman Anthony Rizzo, who had to dive to the pad to make any play. The call was out, but several television replays showed Giménez safe by a couple of hairs. Perhaps too mindful of having lost three prior challenges in the set, the Guardians’ replay review crew didn’t move a pinkie. Francona seemingly didn’t urge them to do so.

Never mind that it would have extended the inning and given the Guards a chance to turn their batting order around sooner, get Cortes out of the game sooner, and get into that still-vulnerable Yankee pen sooner. Francona’s been one of the game’s most tactically adept skippers for a long enough time, but not nudging his replay people to go for this one helped further to cost him an ALCS trip.

These Yankees don’t look proverbial gift horses in the proverbial mouths. An inning later, with Torres on first with a leadoff walk and James Karinchak relieving Trevor Stephan following a Judge swinging strikeout during which Torres stole second, Rizzo lined a single to right to send Torres home. That was all the insurance the Yankees ended up needing.

Especially when these so-called Guardiac Kids, the youth movement whose penchant for small ball and for driving bullpens to drink with late rallies, forcing the other guys into fielding lapses, winning a franchise-record number of games at the last minute, had nothing to say against three Yankee relievers who kept them scoreless over a final four solid shutout innings.

Especially when they actually out-hit the Yankees 44-28 and still came up with early winter. The trouble was, the Guards also went 3-for-30 with men in scoring position over Games One, Two, Four, and Five, and had nobody landing big run-delivering blows when needed the most. Their ability to surprise expired.

Now the Yankees have a chance for revenge against the Astros who’ve met them in two previous ALCSes and beaten them both times. They had to hurry their postgame celebration up considerably—the ALCS opens Wednesday night.

The Guardians could take their sweet time going home for the winter and pondering the season that traveled so engagingly but ended so ignominiously.

“Winning the division was the first part,” Hedges said postgame. “Wild-card round. Put ourselves in position to beat the Yankees. And we wanted to win the World Series, but that’s a good Yankees team. The cool thing is, now we have a bunch of dudes with a ton of playoff experience in the most hostile environment you can imagine.”

The Guards were bloody fun to watch for most of it. Then Cole, Stanton and Judge rang their bells in Games Four and Five, and they had nothing much to say in return. The Guardiac Kids were the babies who got rocked. There was nothing much fun about that.