“We need to rank the umpires . . . and talk about relegating (the bottom ten percent) to the minor leagues.”—Max Scherzer.

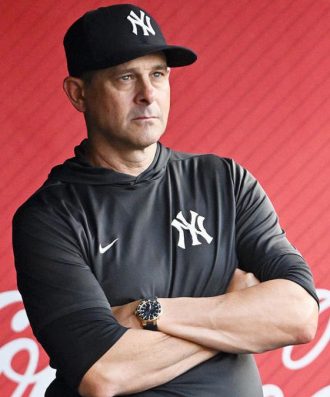

Hunter Wendelstedt’s toss of Yankee manager Aaron Boone Monday has now been deemed “a bad ejection,” according to SNY’s Andy Martino, citing an unnamed source. “Bad ejection?” How about unwarranted? How about irresponsible? How about letting reputation overrule the moment erroneously?

And, how about Max Scherzer suggesting a very good way to start holding umpires better accountable for such unwarranted, irresponsible errors?

Nobody with eyes to see and ears to hear should have cared two pins that Boone had 34 previous ejections plus a reputation for being a bit on the whiny side. Boone kept his mouth tight shut following an early warning over a beef involving a hit batsman on a low pitch, but a blue-shirted fan seated behind the Yankee dugout barked and Wendelstedt decided Boone should get the bite.

Wendestedt not only ejected a manager erroneously but doubled down with one of the most mealymouth explanations you’re liable to hear from anyone among the people who are supposed to be the proverbial adults in the room:

This isn’t my first ejection. In the entirety of my career, I have never ejected a player or a manager for something a fan has said. I understand that’s going to be part of a story or something like that because that’s what Aaron was portraying. I heard something come from the far end of the dugout, had nothing to do with his area but he’s the manager of the Yankees. So he’s the one that had to go.

Imagine parents hearing one of their children call them an obscene name while in another’s bedroom, then deciding the child whose bedroom it is should be grounded a week instead of the pottymouth. That’s what Wendelstedt’s ejection was, and the crime didn’t happen from the Yankee dugout but behind it.

The only thing MLB government intends to do, Martino observed, is add the Boone ejection to Wendelstedt’s evaluation for game management. Seasonal evaluations have impacts on whether umpires get plum assignments such as leading crews, working All-Star Games, and working postseasons.

Wendelstedt isn’t a crew chief despite being a major league ump for 28 years. (He works today on Marvin Hudson’s ump crew.) He hasn’t worked an All-Star Game since 2011; he hasn’t worked a postseason series since the 2018 National League Championship Series. You might consider thirteen years since his last All-Star game and eight since his last postseason assignment punishment enough.

But players, coaches, managers are subject to prompt accountability for their misbehaviours. They get fined and/or suspended for bad arguments on the field and MLB government can’t wait to make those punishments public. Blocking an errant ump from the postseason may seem like punishment to you, but how much damage might his regular-season mistakes and doubling down on mealymouth excuses for them have wreaked upon a pennant race?

On 26 July 2011, plate ump Jerry Meals ruled incorrectly that the Braves’ Julio Lugo was safe at the plate in the bottom of the nineteenth on 26 July 2011. Pirates catcher Michael McKenry tagged him out three feet from the plate, and you can see McKenry make the tag right before Lugo stepped on the plate.

Meals apologised profusely after the game and the day after. (He also incurred death threats against his wife and children.) His public acknowledgement of his mistake may have saved his hide; he got to work a 2011 NL division series and was promoted to crew chief in 2015, a rank he held before his retirement in 2022.

But that call cost the Pirates a win after a very long night and helped knock the wind out of their pennant race sails. They were a game out of first in the National League Central when that game ended. They split the next two games with the Braves before hitting a ten-game losing streak, losing fourteen of their next sixteen, and falling to fourth in the division to stay.

There are and have been those umps such as Meals who hold themselves accountable for their mistakes. Umps such as also-retired Jim Joyce and Tim Welke, and still-working Chad Fairchild. Umps such as the late Don Denkinger, who owned up to his infamous 1985 World Series mistake and also came out strong for replay.

Umps such as Gabe Morales, who seemed itching to apologise for blowing the call—when plate ump Doug Eddings asked for help on Wilmer Flores’s check swing, bottom of the ninth, two out and a man on first, the Giants down one run, Game Five of a 2021 NLDS riddled with dubious calls—for game, set, match, and early winter for the Giants. We’ll never know if Flores would have risen to the occasion on 1-2, whether against Max Scherzer or Marvin the Martian, but he should have the chance to try.

What to do about the Wendelstedts? About the Angel Hernandezes, Laz Diazes, C.B. Bucknors? Now pitching on a rehab assignment at Round Rock for the Rangers, Scherzer himself has a thought. A very good one. You’re afraid of Robby the Umpbot? Max the Knife says not so fast, Robby might actually do us a huge favour if he’s deployed properly and baseball government doesn’t screw his pooch:

We need to rank the umpires. Let the electronic strike zone rank the umpires. We need to have a conversation about the bottom—let’s call it 10%, whatever you want to declare the bottom is—and talk about relegating those umpires to the minor leagues.

Scherzer’s said something I’ve argued before. Remember: relegating low-ranking, low-performing umpires to the minors for retraining is precisely what the Korean Baseball Organisation does. If MLB’s government can’t get the World Umpires Association to sit down and talk seriously and reasonably about umpire accountability without Robby the Umpbot, maybe the point that many umps aren’t exactly paranoid about Robby’s eventual advent offers a way to get it without undermining umps or bruising egos too seriously.

Accountability is an absolute must. Max the Knife’s thought put into play would be a far better look than leaving the Wendelstedts excuses to double down on their most grievous errors and verbal diarrhea to follow, or leaving baseball’s government excuses to continue letting them get away with it.