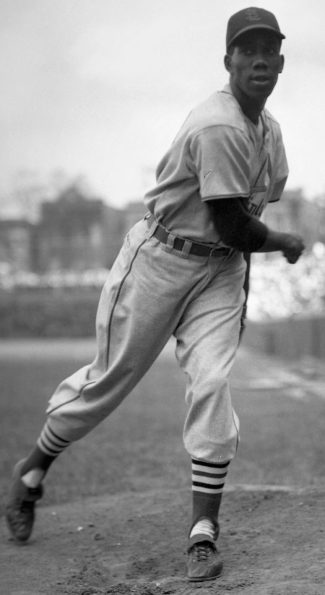

Cepeda was the Giants’ first San Francisco idol from the moment he emerged in 1958.

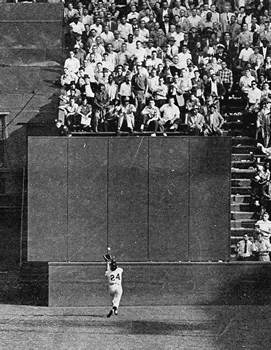

It took the late Hall of Famer Willie Mays more time than he deserved to become a San Francisco treat as a New York import. It took the now-late Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda, who died Friday at 86, five minutes during the Giants’ first season by the Bay.

OK, that’s only a slight exaggeration. But having no tie to the Giants’ New York past, having a blast against the Dodgers in the Giants’ first San Francisco regular season game (a home run against Don Bessent with one out in the fifth), and posting a Rookie of the Year season with 25 bombs and a National League-leading 38 doubles, Cepeda became a Giants’ matinee idol at once.

It didn’t hurt that this son of Puerto Rican baseball legend Pedro (The Bull) Cepeda found San Francisco a treat from the word go, either. “Right from the beginning,” the Baby Bull would remember to Sports Illustrated‘s Ron Fimrite in 1991.

There was everything that I liked. We played more day games then, so I usually had at least two nights a week free. On Thursdays, I would always go to the Copacabana to hear the Latin music. On Sundays, after games, I’d go to the Jazz Workshop for the jam sessions. At the Blackhawk, I’d hear Miles Davis, John Coltrane . . . I roomed then with [outfielder] Felipe Alou and [pitcher] Rubén Gómez, but I was the only one who liked to go out at night. Felipe was very religious and quiet, and Rubén just liked to play golf, so he wasn’t a night person. But I was single, and I just loved that town.

Show me a ballplayer who loves a good jazz jam and I’ll show you my kind of ballplayer, folks. The only thing that would make my jazz heart go pitty-pat a little more would be discovering Cepeda in the Blackhawk audience on the April 1961 nights that produced the classic Miles Davis In Person Friday and Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk.

Imagining the smiling Cepeda at the Blackhawk raptly listening to a Davis quintet running the range from Miles’ modal classic “So What” to Thelonious Monk’s equally classic “Well, You Needn’t” and back to, say, Johnny Mercer’s “Autumn Leaves” or Miles’s own blues, “No Blues,” is an imagining worth securing.

The sole sore spot was Cepeda’s early tussle with fellow Giants comer/Hall of Famer Willie McCovey for playing time at first base. Cepeda won the early battles when McCovey, an equally likeable soul, struggled to find consistency, compelling Giants manager Bill Rigney to switch the pair off between left field and first base, a switchoff that didn’t always sit right with Cepeda.

“I know I could’ve played left field if I’d put my mind to it,” he’d remember to Fimrite, “but I was only 21 years old and very sensitive. Friends and other players kept telling me I should demand to play first. It was all pride with me. And ignorance.”

A 1961 knee injury left Cepeda to play in pain for most of the rest of his Giants tenure, but it didn’t stop him from leading the National League with 46 home runs and finishing second to Hall of Famer Frank Robinson in the league’s Most Valuable Player Award vote. Somehow, Cepeda would manage to post performances through age 26 that would make him a rival to Hall of Famers Jimmie Foxx and Lou Gehrig (and, retroactively, Hall of Famer in waiting Albert Pujols) for first basemen.

The knee pain was nothing compared to the psychic pain of playing for Rigney’s successor manager Alvin Dark. Dark was known too well to mistake Cepeda and his fellow Latinos’ effervescence for indifference, to say nothing of Dark despising their speaking Spanish among each other. The manager also thought Cepeda was exaggerating the extent to which his knee bothered him.

“Some people think that because we are Latins — because we did not have everything growing up — we are not supposed to get hurt,” he told another SI writer, Mark Mulvoy, in 1967. “But my knee was hurt. Dark thought I was trying not to play. He treated me like a child. I am a human being, whether I am blue or black or white or green. We Latins are different, but we are still human beings. Dark did not respect our differences.”

Dark’s successor, Herman Franks, suspected Cepeda of loafing in spring 1965 when in fact Cepeda found it difficult to put his full weight on the bothersome knee. He’d spend May through August on the disabled list, have surgery on the knee in the offseason, and lose the first base job to McCovey at last. In May 1966, after another spell in left field and despite hitting reasonably, Cepeda was traded to the Cardinals for pitcher Ray Sadecki.

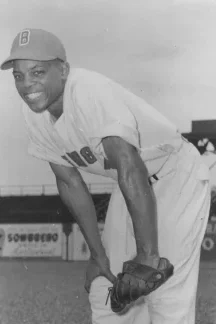

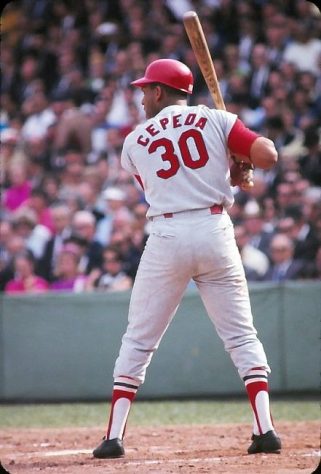

Shocked at first, Cepeda welcomed the deal quickly when he made two discoveries. The Cardinals needed a first baseman in the worst way possible, and his new teammates plus manager Red Schoendienst took a quick liking to his upbeat personality and his equal loves for jazz and Latin music. They nicknamed him Cha-Cha; he returned the favour by nicknaming the 1967 Cardinals El Birdos.

He nicknamed his 1967 Cardinals El Birdos, and they went on to win that World Series while he won the NL’s MVP.

Well, now. El Birdos would go all the way to winning the World Series and Cha-Cha would go all the way to winning the NL’s MVP. Inexplicably, though there’s always the chance that his repaired right knee might still have tried to rebel, Cepeda went from first to worst of his career to date, sort of, in 1968. Hoping to make a 1969 comeback, he was dealt to the Braves for catcher/third baseman Joe Torre before spring training ended.

Leery about the South (he’d learned the hard way about Jim Crow as a minor leaguer in Virginia over a decade earlier), Cepeda relaxed when reunited with former Giants teammate Felipe Alou and making a new friendship with Hall of Famer Henry Aaron. His regular season was a struggle, but in the new divisional play format with the Braves winning the NL West, Cepeda hit a ton in a losing cause (1.448 OPS) as the Braves got swept in the best-of-five by the Miracle Mets.

He hit a ton in 1970 (34 bombs; .908 OPS) as the Braves fell to fifth place otherwise, but in 1971 his good knee gave out on him. He’d never be the player he once was again other than a surprise 1973 in which he became the Red Sox’s first official designated hitter. Released for youth in 1974, he tried a comeback in the Mexican League and a brief spell with the Royals before calling it a career at last.

Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente’s tragic death in 1972 led Puerto Rico to anoint Cepeda a hero, but in December 1975 his astonishing arrest for accepting a delivery of 170 pounds of marijuana (he claimed he was expecting a smaller amount, for himself) sent him from hero to poison. There wasn’t a jazz performance alive that could save him from that.

“He and his family received death threats,” observed his Society for American Baseball Research biographer Mark Armour. “He lost all of his money on his legal case, which caused him to miss child-support payments and led to more legal trouble. He finally stood trial in 1978, was found guilty, and was sentenced to five years in prison. He served ten months in a minimum-security facility in Florida.”

Cepeda struggled further after his release, losing a job as a White Sox minor-league hitting coach and his second marriage. Somehow, he took up Buddhism and there lay the key to changing his life permanently. “It allowed him to take responsibility for the mess he had made of his life,” Armour wrote, “to get control of his shame and his anger, and to help him find a path forward. He also met Mirian Ortiz, a Puerto Rican woman who eventually became his third wife. He and Mirian moved to the Bay Area, close to where his baseball journey had begun 30 years earlier.”

“Buddhism cleared the air for me,” Cepeda said. “I discovered that winter always turns to spring.”

In time, Cepeda re-established ties with the Giants, first with fantasy camps, then with scouting and roving instruction, and finally as a humanitarian ambassador. He was also elected to the Hall of Fame by the 1999 Veterans Committee, the second Puerto Rican (behind Clemente) to be elected, five years after he missed Baseball Writers Association of America election by seven votes in his final year of eligibility.

Shy of a decade later, Cepeda became the fourth Giant to be immortalised in bronze outside what’s now Oracle Park, joining Mays, McCovey, and Hall of Fame pitcher Juan Marichal, shown standing tall with his customary smile, wearing a first baseman’s mitt and holding a baseball inches from the webbing. It was a long, hard enough road for the man who’d had to use his Giants signing bonus to pay for his father’s funeral.

Let’s pray his widow and five sons find comfort in his eternal serenity in the Elysian Fields. And, that they can’t resist saying, “It figures,” if they discover one of the first things he did upon arrival was seek out a Miles Davis Quintet here, a John Coltrane Quartet there, a Mongo Santamaria group yonder, and engage the only swinging that ever engaged him above and beyond his own with a bat.