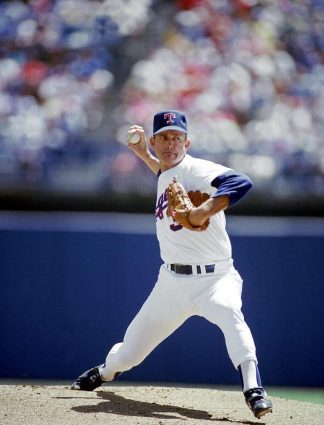

Andrew Benintendi hitting the two-run homer that started the White Sox on the way to ending their franchise-worst, AL record-tying losing streak Tuesday night.

In a way, it almost figured that the end would happen on the road. Something about this year’s White Sox just didn’t cry out that they should end the single most miserable spell in their history this side of the Black Sox scandal before their home people.

Maybe it was the distinct lack of humour. Nobody likes to lose, nobody likes when losing becomes as routine as breakfast coffee, but there have been chronically losing teams who managed to laugh–even like Figaro that they might not weep . . . or kill.

The 1988 Orioles survived their record season-opening 21-game losing streak with gallows humour. This year’s White Sox didn’t dare adopt gallows anything, perhaps out of fear that their own odious owner might take them up on it, build a gallows, and send a different team member to it each postgame.

My God, when these White Sox finally found better angels upon whom to call and beat the Athletics 5-1 Tuesday night, the funniest thing about it was that nobody could find a beer to drink in the postgame clubhouse celebration—because the entire supply had been poured over each other once they came off the field.

“A beer shower, what are you talking about,” cracked White Sox relief pitcher John Brebbia, who got three straight air outs in the bottom of the ninth to finish what Andrew Benintendi’s two-out, two-run homer started in the top of the fourth. “I’ve never heard of such a thing. That’s absurd.”

As if he’d suddenly been made aware he’d almost crossed the no-humour line, Brebbia plotted his own course correction. “We’ve got a day game tomorrow,” he said, “so guys are super focused on getting some sleep. Making sure they’re eating right and supplementing properly.”

Sure. Bust the franchise’s longest losing streak ever, keep them tied with the 1988 Orioles as the American League losing streak record holders, and do nothing more than check and maintain their diets, pop the right vitamins, and don’t be late for their dates with Mr. Sandman.

No White Sox player, coach, clubhouse worker, or front office denizen expected that kind of losing streak, of course. Not even with owner Jerry Reinsdorf executing his longtime leadership tandem of Ken Williams and Rick Hahn. Not even when Reinsdorf looked no further than his own hapless assistant GM Chris Getz to succeed the pair—fast. Not even with White Sox fans, what’s left of them, take pages from the book of A’s fans and hoist “Sell the Team” banners at Guaranteed Rate Field.

Not even the most shameless tankers of the past decade went into seasons expecting double-digit losing streaks at all, never mind record tyers or record threateners. But these White Sox might yet overthrow the 1962 Mets and their 40-120 season for record-setting futility. 38-124, anyone? No one’s saying that’s impossible yet.

Those Mets actually had no losing streak longer than seventeen games. They were also shut out a mere six times while they actually managed to shut the other guy out four. These White Sox have managed somehow to shut the other guys out one more time than that, but they’ve also been shut out thirteen times and possibly counting. Perhaps more amazing than those Original Mets, these White Sox were shut out only once during the now-ended losing streak. (A 10-0 blowout by the Mariners.)

The ’88 Orioles ended their notorious losing streak with a win against the White Sox that also involved eight Orioles and only three White Sox striking out at the plate. Last night, four White Sox batters struck out and five A’s did as well. The first strikeout wasn’t nailed until the bottom of the third, when White Sox starter Jonathan Cannon ended the side by blowing A’s catcher Sean Langoliers away on a climbing fastball.

To the extent that you could call it a pitching duel, the White Sox and the A’s seemed more bent on settling who could get more ground outs than fly outs. The White Sox pitchers landed eleven ground outs and sixteen air outs; the A’s pitchers, ten ground outs and nineteen fly outs. As if both teams believed idle gloves were the devil’s playthings.

The White Sox also left three men on base to the A’s leaving seven. Maybe the sleekest defensive play of the game ended the Oakland second, when White Sox shortstop Nicky Lopez handled A’s left fielder Lawrence Butler’s hopper on the smooth run and executed a smoother-than-24-year-old-scotch step-and-throw double play.

Then, in the top of the fourth, White Sox center fielder Luis Robert, Jr. slashed a clean line single to left with one out. First baseman Andrew Vaughn flied out to right to follow, but then Benintendi turned on A’s starter Ross Stripling’s 1-1 fastball right down the chute and sent it far enough over the right field fence.

This time, the White Sox would not blow the lead. Not even after A’s second baseman Zack Geldof hit a two-out solo homer in the bottom of the inning. Would anyone guarantee a White Sox win with a mere 2-1 score? The White Sox themselves wouldn’t have.

First, Sox third baseman Miguel Vargas wrung Stripling for a leadoff walk in the top of the sixth. Brooks Baldwin, a youthful midseason addition who had yet to be part of a major league victory, promptly singled him to second. One out later, Vaughn singled Vargas home and Baldwin to third with a base hit, chasing Stripling. Reliever Michel Otanez wild-pitched Baldwin home with Vaughn stealing third as Otanez worked on Sox designated hitter Lenyn Sosa—who flied out for the side but left the score 4-1, White Sox.

Maybe that still wouldn’t be enough. As the redoubtable Jessica Brand Xtweeted, the White Sox pre-Tuesday had one game since the Fourth of July in which they had a three-plus-run lead in the eighth or later, a 5-2 lead against the Royals on 29 July. Oops. The Royals dropped three homers including a grand slam to make it an 8-5 Royals win and White Sox consecutive loss number fifteen.

Come Tuesday, the White Sox turned out to have one more card to play in the top of the ninth. Benintendi doubled to right with one out, took third on a wild pitch with Sosa at the plate, then Sosa sent Benintendi home with the RBI single, before Brebbia made short air-out work of the A’s in the bottom to close a deal that once seemed about as likely as finding coherence coming from Donald Trump’s or Joe Biden’s mouths.

So what did Benintendi—once upon a time the acrobat who charged and dove to steal a certain three-run triple from Houston’s Alex Bregman, sending the 2018 American League Championship Series into a two-all tie rather than leaving it 3-1 Astros—think after he and his White Sox finally closed the book on their team-record, league-record-tying losing streak?

“We won a game, nothing more than that,” he said postgame. “I think everybody has played enough baseball. You understand that we play 162 of them. It sucks that we’ve lost 21 in a row, but a win’s a win. We’re all excited obviously, but this is no different than any other win.”

Maybe it was exhaustion. Maybe it was unexpected relief that the White Sox didn’t become the new AL losing streak record holders. When Benintendi hauled down Gelof’s towering fly to shallow left to end the game and the streak, he didn’t even want to keep the ball as a souvenir.

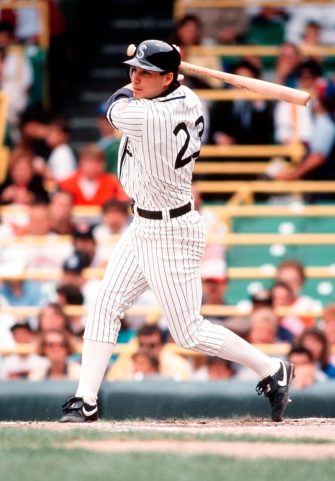

Two traveling White Sox fans urge the team on indicating they were one out from the Promised Land Tuesday night.

Sox manager Pedro Grifol, who’s just about guaranteed to be left to find new employment, possibly when the season finally ends, possibly sooner, was almost as benign as that when the streak ended. “It was cool to watch for nine innings, these guys pull for each other,” he said. “The [Coliseum] dugout is small, but nobody really cared about how small it was today. It was just a group of guys, together, trying to see if we could get this thing behind us.”

That may have been one of the least testy postmortems of the year for these Sox. Grifol is no Casey Stengel. Not as a baseball tactician or strategist, and certainly not as a riffer with a twist who could keep the heat off his hapless charges at the lowest of their low.

“Come an’ see my amazin’ Mets,” Stengel often hectored Polo Grounds fans waiting to see the latest of the 1962 Mets. “I been in this game a hundred years but I see new ways to lose I didn’t know were invented yet.”

Grifol could never cut the mustard at Stengel’s hotel bar roost. His White Sox already sank under the weight of underwhelming individual performances and a small swarm of injury bugs. They incurred embarrassment when a few of the men they sent elsewhere around the trade deadline shone at first for their new teams. They’ve needed a Stengel badly this time around. They’ve barely got a Marx Brother—Zeppo.

A 21-game losing streak that followed a May-June fourteen-gamer was above and beyond Grifol’s and his White Sox’s comprehension no matter what. So much so that they rarely if ever found any reason to laugh while they threatened but didn’t pass the ’88 Orioles. But it’s tough enough being a White Sox fan these days, isn’t it? Do the fans have to provide all the humour?

Apparently. Before Gelof checked in at the plate in the bottom of the ninth, a pair of White Sox fans who’d gone west hoping to see the streak end stood behind the visiting dugout. They made motions indicating to White Sox players, just one out from the Promised Land of a win, any win.

One wore a brown paper bag over his head.

“Will anyone be writing any books about these White Sox?” asked a Tuesday editorial by the Chicago Tribune. Then, they answered.

If only the legendary Tribune columnist Mike Royko were still with us, we’d love to see what he would produce, given his rants back in the day about the hapless Cubs of the 1970s. But those Cubs teams were the 1927 Yankees compared with the 2024 Sox. Even Royko might be at a loss for words on the 2024 White Sox.

How rich is that? Name one other baseball team who could, in theory, have left Mike Royko lost for words, with or without a paper bag over his head. That would have been bigger headlines and more viral memes than any moment in which the White Sox finally played way over their own heads to end their horrific streak. Bigger, even, than the Rangers’ Corey Seager ruining Astro pitcher Framber Valdez’s no-hitter with a two-run homer in the ninth Tuesday.

“They played a good, clean game tonight, and we didn’t generate any offense,” said A’s manager Mark Kotsay postgame. “For that club over there, I’m sure they’re excited about ending their losing streak.” Excitement, apparently, remains in the eye and ear of the beholder.