Andrew Benintendi–his RBI single walking off a second straight White Sox win Wednesday night a) made him the first White Sox player to walk it off thrice in a year since Scott Podsednik in 2009; and, b) helped the White Sox refuse to go gently into that good gray night where record-breaking season losses live.

Baltimore’s long gone but still remembered Memorial Stadium was built as a shrine to those who fought in both world wars. On its façade, these words were posted: Time Will Not Dim the Glory of Their Deeds. The words could also have applied to the baseball team who played there before the advent of Camden Yards

To the Orioles, when they finally won a game in 1988 after 21 consecutive season-opening losses. And, to the second-longest run of sustained excellence in American League history (1960-1985, the Orioles having only two losing seasons in that quarter century span), behind the Yankees’ 45 years of winning records from 1919-1964, now relegated to memory alone.

Today’s Yankees and Orioles are both going to the postseason. But the Yankees look to have the American League East in hand and in the safe, even if there’s still no set-in-stone guarantee of their getting as far as the World Series. (And do remember the Yankee fan’s credo of entitlement that the Series is illegitimate without them.)

That’s after the Orioles went from spending 81 days atop the division including as much as a three-game advantage to second place and five games back of the Yankees thanks largely to winning only five of their last fifteen. Once on pace to win 104, a rash of injuries, especially to pitchers and infielders, leaves Oriole fans wondering whether their birds have flown since their May peak.

But both those teams would sure as hell rather not switch places with this year’s AL doormats, on the façade of whose ballpark won’t read a paen to glory but might instead read from a vintage Negro spiritual: Were we really there when this happened to us?

The White Sox’s longest period of sustained excellence (seventeen years) began the same year Edward R. Murrow premiered See It Now with history’s first live coast-to-coast telecast and ended the same year as did the first Apollo astronauts’ lives in a launch pad fire. Their longest period of sustained single-season failure began with a 1-0 loss to the Tigers on 28 March this year.

It still seems given that these Blight Sox will break the 1962 Mets’ record for regular season losses. It could have happened Tuesday night but for the Sox doing what some people have become conditioned to believe can’t be done in White Sox uniforms: they turned a 2-0 deficit into what proved a 3-2 win with an RBI double and a pair of RBI singles in the eighth inning.

Of course, these being the White Sox, that game couldn’t be complete without some sort of mishap. Hark back to the fifth inning, when four Sox converged upon a popup around the right side of the home plate side of the infield and the ball hit the turf like a safe dropped onto a sidewalk from the fourteenth floor.

That was probably the most 1962 Metsian these Blight Sox, these White Sux, these Wail Hose, these South Blindsiders have been all season long. Until this month, the least likely development in 2024 baseball seemed the White Sox developing something heretofore bereft from their calamity and in their play: a sense of humour.

Tuesday night was also the first White Sox win this year in any game in which they trailed after seven innings. “People here tonight were trying to see history,” said left fielder Andrew Benintendi, who hit the RBI double that began the eighth-inning party. “They’re going to have to wait one more day. Maybe.”

Three years ago, the White Sox won the AL Central. The following season, microcosmically amplifying the division’s overall modesty, they finished second with a .500 record. (Exactly 81-81.) Last year, they went 61-101. None of the latter two prepared them for this season and this surrealistic collapse.

“A disaster of this magnitude must have multiple tributaries,” write ESPN’s Buster Olney and Jesse Rogers, in what must surely be the most obvious Captain Obvious utterance since Casey Stengel said of Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio, a player with whom the Ol’ Perfesser didn’t always see eye-to-eye, “He was rather splendid in his line of work.” But the dynamic duo (Olney and Rogers, that is) proceed forth:

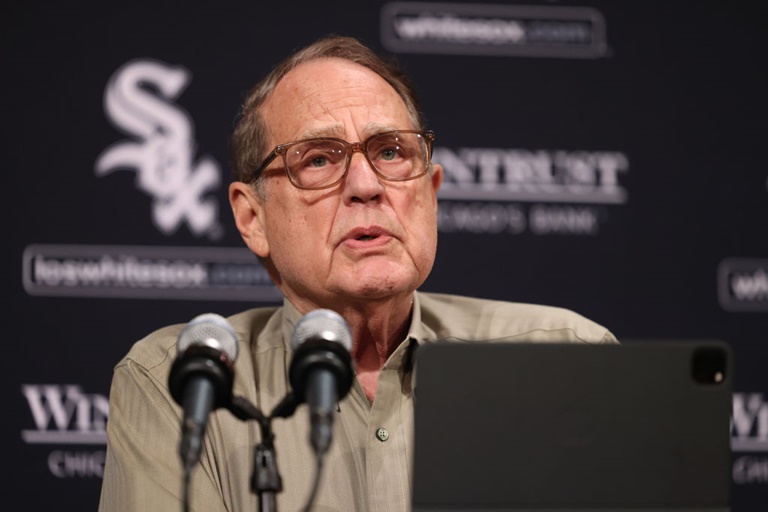

It’s not only about the decades-long habit of owner Jerry Reinsdorf loyally clinging to employees past peak effectiveness. “Old news,” said one staffer. It’s not only about a wave of injuries; lots of teams deal with a lot of injuries. It’s not only about a first-time manager [read: long-since deposed Pedro Grifol–JK] whose tenure was infected by a toxic clubhouse mix. Lots of teams have veterans who don’t get along, though the White Sox seemed to have had more than their share. It’s not only about a handful of players performing at their worst. It’s not only about a first-time general manager taking his first turn on the learning curve. It’s not necessarily about spending—in an era in which teams have slashed payroll to facilitate tanking, the White Sox’s payroll is about $145 million, ranked 18th among 30 teams.

According to more than two dozen sources inside and outside the organization, it’s all of that, together. Over the course of the season, there were missteps from every level of the organization—and just plain bad baseball—that turned the 2024 White Sox from a bad team into a historically awful one.

Once upon a time, Red Sox-turned-Brewers first baseman George (Boomer) Scott told then-Brewers chairman Ed Fitzgerald, “You know, Mr. Fitzgerald, if we’re gonna win, the players gotta play better, the coaches gotta coach better, the manager gotta manage better, and the owners gotta own better.” That fine fielding, power-hitting first baseman didn’t get to live to see these Blight Sox.

Once upon a more distant time, Bill Veeck marveled of the 1962 Mets, “They are without a doubt the worst team in the history of baseball. I speak with authority. I had the St. Louis Browns. I also speak with longing . . . If you couldn’t have fun with the Mets, you couldn’t have fun anyplace.” That from the man who owned the White Sox twice in his lifetime, won one pennant the first time, and survived the infamous Disco Demolition Night in his second go-round.

Grady Sizemore’s signature achievement since succeeding the deposed Grifol has been, seemingly, to ease the toxins out of the White Sox clubhouse. That alone graduated him from not a topic to on the list of candidates for the permanent managing job. His cheerful ways of finding glasses half full aren’t the worst things to happen to his team this year. Even if, as Olney and Rogers remind us, he got this gig purely because the players liked him.

The White Sox players now seem a lot less ready to throw each other under the proverbial bus. Most indications seem to be that they’re more likely to talk to each other in a let’s-go-get-’em-tomorrow mood, even if they’re the ones most likely to get got. There even seems a chance that when (not if) they pass the ’62 Mets, the White Sox might heave sighs of relief in the form of more gallows jokes.

First, they have to get there. Walking it off on Benintendi’s bottom-of-the-tenth RBI single for a 4-3 win against those Angels Wednesday night was either a continued re-awakening or prolonging the agony. Or, it was a simple declaration of, Not in our house!

They have one more with the Angels at home, then a three-game set with the Tigers in Detroit to finish the season. They now seem bent on refusing to go gently into that good gray night, but the odds of them passing those ’62 Mets are still on their negative side.

These White Sox may not say of their too-unique season in hell, Time will not dim the glory of our misdeeds. But would you blame them for the temptation?