Your American League East champions, who got here the hard, disgraceful way.

You hate to dump rain upon the Oriole parade just yet. But their clinch of both the American League East and home field advantage through the end of the American League Championship Series (if they get that far in the first place) isn’t exactly the early climax of a simon-pure story.

Of course it’s wonderful to see the Orioles at the top of their division heap and Baltimore going berserk in celebration. Of course it’s wonderful to see the first team in Show history ever to lose 100+ in a season flip the script and win 100 within three years.

Of course it’s wonderful that the Orioles are going to stay in Camden Yards for three more decades at least, an announcement that came in the third inning Thursday. It sent the audience almost as berserk as they’d go when Orioles third baseman Ramón Urias threw the Red Sox’s Trevor Story out off a tapper to secure the clinch.

Of course it’s wonderful that we don’t get to call them the Woe-rioles, or the Zer-Os anymore. And of course it’s going to feel like mad fun rooting for the Orioles to go deep in the postseason to come, even one that remains compromised by too many wild cards and too many fan bases thus lost in the thrills and chills of their teams fighting to the last breath to finish . . . in second place or even beyond for a nip at the October ciders.

Unfortunately, it’s not easy to forget how the Orioles got to this point in the first place. In plain language, they tanked their way here. There’s no way to sugarcoat it.

However marvelous and resilient they were all season, however much of a pleasure it’s been to see this year’s Orioles behaving like their illustrious predecessors of 1966, 1970, 1983, and numerous other division champions and pennant winners, they got here via tanking. That should never be forgotten. It should never happen again. To the Orioles or any other conscientious major league team.

It started after their 2016 season ended too dramatically. When then-manager Buck Showalter kept to his Book and his Role Assignments, declined to have his best relief pitcher Zack Britton ready and out there, because it wasn’t a quote save situation. Leaving faltering Ubaldo Jimenez on the mound to face Toronto’s Edwin Encarnación. Baltimore still won’t forget the three-run homer Encarnación parked in the second deck of Rogers Centre with the Blue Jays’ ticket to the division series attached.

They tanked from there forward, picking up from where they left off after 1988-2015. They finished dead. last. in the AL East in three of the four seasons to follow. (A fourth-place finish broke the monotony.) As of a hot August 2021 day when the Angels (of all people) bludgeoned them 14-8, including thirteen runs over three straight innings, they were 201-345—after having been the American League’s winningest regular-season team from 2012-2016.

Before the 2021-2022 owners lockout ended and spring training began, The Athletic‘s Dan Connolly came right out and said it, even though he admitted it didn’t really bother him: rebuilding the entire organisation, ground up, and giving almost all attention to the minors and the world baseball resources but so little to the parent club, “produces a tank job in the majors.”

They weren’t the only tankers in the Show by any means. Famously, or perhaps infamously, the Astros tanked their way to the 2017 World Series—which turned out to be tainted thanks to the eventual revelations that the 2017-18 Astros operated baseball’s most notorious illegal, off-field-based, electronic sign-stealing scheme.

They were preceded by the 2016 Cubs, who tanked their way to that staggering World Series conquest. Like the Astros, the Cubs came right out and said it: they were going into the tank in order to win in due course. The 2016 Cubs don’t have the 2017-18 Astros’ baggage, and their conquest was mad fun, but their fans endured a few seasons of deliberate abuse to get there.

Yes. I said it again. Just like Thomas Boswell did in July 2019. “It’s dumb enough to tear down a roster that is already rotten or old or both,” he wrote.

But it’s idiotic to rip up a team that has a chance to make the playoffs, even as a wild card, especially in the first era in MLB history when six teams already are trying to race to the bottom. With more to come? What is this, the shameless NBA, where tanking has been the dirty big lie for years?

. . . With the Orioles (on pace for 111 loses), Tigers (111), Royals (103), Blue Jays (101), Marlins (101) and Mariners (98) all in the same mud hole wrestling to get the same No. 1 draft pick next season, we’re watching a bull market in stupidity. And cupidity, too, since all those teams think they can still make a safe cynical profit, thanks to revenue sharing, no matter how bad they are . . .

. . . In the past 50 years, losing usually leads to more losing — a lot more losing. I’ve watched it up close too often in Baltimore. In 1987-88, the Birds lost 202 games. Full rebuild mode. In the 31 seasons since, the Orioles have won 90 games just three times. At one point, they had 14 straight losing seasons. Why did D.C. get a team? Because the Orioles devalued their brand so much that there was nothing for MLB’s other 29 owners to protect by keeping a team off Baltimore’s doorstep.

Baseball has seldom seen a darker hour for its core concept of maintaining the integrity of the game. Commissioner Rob Manfred is either asleep or complicit.

Too many teams are now breaking their implicit vows to the public. They’re making a profit through the back door as money gushes into the game from revenue streams, many of them generated over the Internet, which are divided 30 ways. For generations, fans have believed that they were “in it together” with their teams. Bad times made everybody miserable — fans, players and owners alike. Now, only the fans take it in the neck.

And in the back.

So this year’s Orioles, a genuinely fun and engaging team, with a lot of genuinely fun and engaging players, have won 100 games for the sixth time in their franchise history. They have the home field postseason advantage for as long as they endure through the end of the American League Championship Series. They’re liable to make things interesting for any team looking to dethrone them this postseason. Just like their former glory days.

It’s wonderful to see Camden Yards party like it’s 1969 again. Or 1970-71. Or 1979-80. Or the scattered good seasons between then and now. But it should be miserable to think of how they got here in the first place. It should be something no Oriole fan, no baseball fan, really, should wish to see again.

Tanking is fan abuse, plain and simple. It also abuses the game’s integrity. That integrity has taken more than enough shots in the head from other disgraces perpetuated by its lordships. Don’t pretend otherwise.

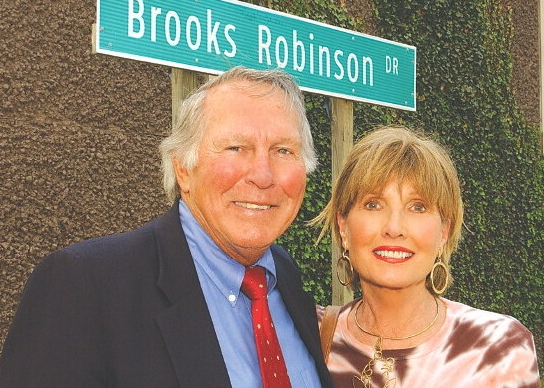

But now that we’ve got that out of our system, for the time being, let’s celebrate. The once-proud organisation that gave us the Brooks-and-Frank-Family Robinson era, The Oriole Way, and the era of Steady Eddie and Iron Man Cal (though beating the 1983 Philadelphia Wheeze Kids could have been called shooting fish in a barrel), is going back to the postseason at last.

And, this time, let’s pray, that when a true as opposed to a Role-or-Book “save situation” crops up in the most need-to-win postseason game, manager Brandon Hyde won’t leave his absolute best relief option in the pen—a dicey question, considering they’ve lost closer Félix Bautista (now to Tommy John surgery), even with Yennier Cano emerging to look like a grand candidate—waiting while a misplaced, faltering arm surrenders a season-ending three-run homer before their time.

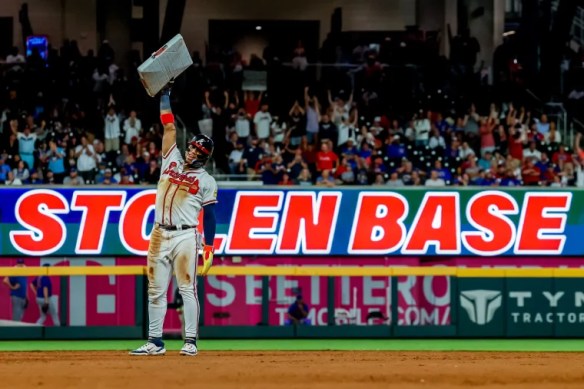

Maybe these guys have what it takes to wrestle their way to a World Series showdown with that threshing machine out of Atlanta. Maybe they won’t just yet. Let’s let Baltimore and ourselves alike enjoy the Orioles’ October ride while it lasts, however long it lasts. The loveliest ballpark in the Show has baseball to match its beauty once again.