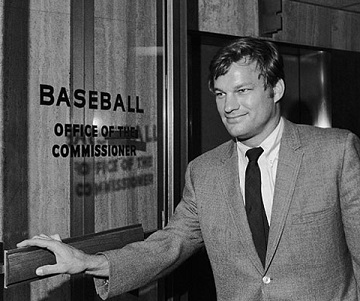

Jim Bouton steps forth from Commissioner Bowie Kuhn’s office and the meeting in which Kuhn tried to suppress Ball Four—based entirely on a magazine excerpt.

Fifty years ago Jim Bouton pitched the season he would record to write Ball Four. Once a glittering Yankee prospect reduced to relief pitching thanks to arm trouble that arose after the 1964 World Series, Bouton’s wryly candid notes, asides, and observations while pitching for the expansion Seattle Pilots and the Astros both humanised and scandalised baseball and enough of its actual or reputed guardians.

By now, of course, Ball Four is the only sports book included on the New York Public Library’s list of 20th Century Books of the Century. And Bouton died Wednesday at 80, at the Massachussetts home he shared with his second wife, Paula Kurman.

A 2012 stroke left Bouton to suffer cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a brain disease linked to dementia that compromised his ability to speak and write. Making it worse: the stroke occurred on the fifteenth anniversary of his daughter Laurie’s death in a New Jersey automobile accident.

Baseball may have gone ballistic when Ball Four hit the ground running in 1970, and Bouton could never be certain whether the Astros sent him down that year because he wasn’t pitching well or because the book was driving the front office and others out of their gourds. But he out-lived enough of his critics, most of the time the living and breathing evidence of the maxim about living well and the best revenge.

And Ball Four keeps company on the New York Public Library list with the likes of T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, Edith Wharton, Ralph Ellison, Jack Kerouac, John Dos Passos, Albert Camus, Agatha Christie, Grace Metalious, and Tom Wolfe.

Go ahead. Say if you must that Bouton didn’t exactly write The Waste Land, Light in August, Invisible Man, On the Road, or The Bonfire of the Vanities. But then T.S. Eliot, William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, Jack Kerouac, and Tom Wolfe never had to try throwing to Harmon Killebrew, Carl Yastrzemski, Frank Robinson, Lou Brock, Frank Howard, or Willie Mays and living to tell about it, either.

To say Ball Four was received less than approvingly around baseball is to say Baltimore needed breathing treatments after the Mets flattened the Orioles four straight following a Game One loss in the 1969 World Series. “F@ck you, Shakespeare!” was Pete Rose’s review, hollered while Bouton had a rough relief outing against the Reds. All things to come considered, it was a wonder Rose knew Shakespeare wasn’t something the tavern served on tap.

Nicknamed Bulldog in his pitching days, Bouton would have been the first to say how fortunate he was to have met and married Kurman, an academic and speech therapist who holds a Columbia University doctorate in interpersonal communications, and who has worked with brain damaged children during her career. She worked with her husband carefully and helped him re-gain much of his speaking ability despite his illness.

“Together we make a whole person,” Kurman once told a Society for American Baseball Research panel, to laughter that was sad as much as approving.

But Bouton struggled concurrently with what Kurman told Tyler Kepner of the New York Times was “a pothole syndrome: Things will seem smooth, his wit and vocabulary intact, and then there will be a sudden, unforeseen gap in his reasoning, or a concept he cannot quite grasp.”

Teammates were divided mostly over Ball Four; they seemed less offended by Bouton’s vivid descriptions of the lopsided contract talks too many players experienced before the free agency era than by his candid descriptions of their clubhouse, off-field, and road off-field activities.

“The first thing I have to tell people,” said his Seattle roommate and fellow pitcher Gary Bell, with whom Bouton maintained a lifelong friendship to follow, “is that you’re not [fornicating] Adolf Hitler.” Bouton wrote in his book that being Bell’s roommate helped make him slightly more tolerable amidst teammates who weren’t exactly forward-looking or thinking. “Every year,” Bouton said of Bell, “I receive a Christmas card addressed to ‘Ass Eyes’.”

Bouton long believed fellow pitcher Fred Talbot (who died six years ago) was the teammate who was quoted anonymously as saying Bouton’s prose “would gag a maggot.” (“When I asked Fred how he was doing,” Bouton would remember in Ball Four‘s tenth anniversary edition’s postscript, “Ball Five,” after a where-is-he-now call to Talbot, “he said, ‘Well, I’m still living,’ and hung up. I didn’t even get a chance to tell him I was glad.”)

And before the Astros sent him to the minors, where he entered what proved a first retirement, unknown members of the Padres left a burned copy of Ball Four on the Astros’ dugout steps.

He got a delicious chance to write about the reaction/overreaction to Ball Four in the just-as-delightful I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, from then-commissioner Bowie Kuhn’s active attempt to suppress Ball Four to New York Daily News sportswriting legend Dick Young ripping him as a “social leper” for having written the book. When Bouton met Young in the clubhouse after that column, Young said hello and Bouton couldn’t resist replying, “Hi Dick, I didn’t know you were talking to social lepers these days.” Young replied genially, “Well, I’m glad you didn’t take it personally.” Little did Young know.

Bouton’s most famous words may well be the ones with which he ended Ball Four: “You spend a good part of your life gripping a baseball, and it turns out that it was the other way around.” But in I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, it may have been an exercise in futility for him to write, ““I think it’s possible that you can view people as heroes and at the same time understand that they are people, too, imperfect, narrow sometimes, even not very good at what they do. I didn’t smash any heroes or ruin the game for anybody. You want heroes, you can have them. Heroes exist in the mind, anyway.”

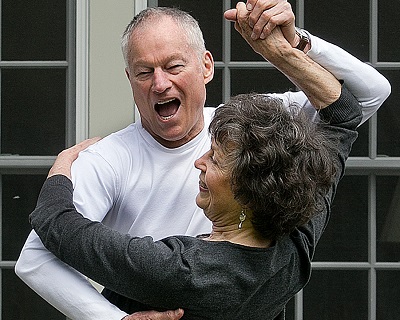

Bouton enjoys a dance with his wife, Paula Kurman, at their Massachussetts home; the couple once competed as ballroom dance partners.

It took a very long time for baseball people to get it. Even longer than it took them to get that the late Jim Brosnan, a decade earlier, wasn’t trying to smash heroes or ruin a game when he wrote The Long Season and Pennant Race, and Brosnan didn’t go half as far as Bouton went in revealing baseball’s inner sanctum even if Brosnan incurred comparable wrath.

“I had . . . violated the idolatrous image of big leaguers who had been previously portrayed as models of modesty, loyalty and sobriety — i.e., what they were really not like,” Brosnan wrote on the 40th anniversary republication of Pennant Race. “Finally, I had actually written the book by myself, thus trampling upon the tradition that a player should hire a sportswriter to do the work. I was, on these accounts, a sneak and a snob and a scab.”

Bouton wrote and recorded Ball Four by himself, too, his editor Leonard Shecter doing nothing much more than knocking it into book-readable condition, as he would for I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally. It didn’t stop Kuhn from hauling Bouton into his office and trying to jam down the pitcher’s throat a statement saying he hadn’t meant it and the whole thing was Shecter’s fault.

Both pitchers were very aware of the worlds around them, and both wrote about the periodic spells of boredom, racial tensions, off-field skirt chasings, and self-doubts endemic in their professional baseball lives. Brosnan saved them for his books and articles; Bouton was less reluctant to speak his mind about things like politics, Vietnam, and civil rights when asked or when a conversation left him the opening.

Bouton bought even less into the still-lingering press representations of athletes as heroes. Teammates didn’t always hold with that or other things, like calling them out on it when they made mistakes that cost the Yankees games he pitched.

“After two or three years of playing with guys like [Mickey] Mantle and [Roger] Maris,” he wrote in I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, “I was no longer awed. I started to look at those guys as people and I didn’t like what I saw. They were fine as baseball heroes. As men they were not quite so successful. At the same time I guess I started to rub a lot of people the wrong way. Instead of being a funny rookie, I was a veteran wise guy. I reached the point where I would argue to support my opinion and that didn’t go down too well either.”

“He stands out,” Shecter wrote of Bouton in Sport, “because he is a decent young man in a game which does not recognize decency as valuable.” Much the same thing was said of Brosnan no matter what particular writers did or didn’t think of his two books.

For decades Bouton believed Ball Four got him blackballed from the Yankees in terms of Old-Timer’s Days and other such events involving team alumni, and that Mantle was the instigator. When one of Mantle’s sons died in the mid-1990s, Bouton left a message of sympathy on Mantle’s answering machine. To Bouton’s surprise, Mantle himself called to thank Bouton and, by the way, say that it wasn’t Mantle who put Bouton in the Yankee deep freeze.

Laurie Bouton’s death prompted her oldest of two brothers, Michael, to write an astonishing op-ed piece in The New York Times calling for the Yankees to reconcile with both his father and with Hall of Famer Yogi Berra, estranged ever since George Steinbrenner fired him as manager through an intermediary in the 1980s. Michael Bouton got what he asked for. In both regards. (Yankee Stadium rocked especially with a section occupied by Laurie’s friends, holding a banner hollering LAURIE’S GIRLS!)

When Bouton retired the first time in 1970, he assembled another book, a splendid anthology of writings about baseball managers and managing called “I Managed Good But, Boy, Did They Play Bad,” then became a sportscaster for New York ABC and CBS. As his first marriage was falling apart, Bouton also tried a baseball comeback. He slogged the minors a couple of years before then-Braves owner Ted Turner abetted his September callup in 1978. After a start that prompted such comments as, “It was like facing Bozo the Clown,” as Bouton eventually recorded (in “Ball Five”), “In his next start, Bozo the Clown beat the San Francisco Giants. The pennant-contending San Francisco Giants.”

Then he tangled with Astros howitzer J.R. Richard. “The young flamethrower and the old junkballer,” Bouton described them. On the same night the towering Richard broke the National League’s single-season strikeout record for righthanded pitchers, the old junkballer fought the young flamethrower to a draw, somehow. In the interim, Bouton and a Portland Mavericks teammate named Rob Nelson cooked up the concoction that became Big League Chew gum, the kind that looked shredded like chewing tobacco, and its success made some nice dollars for Bouton and Nelson.

Bouton ended his brief baseball comeback, satisfied that he’d proven what he tried to prove, and also became a motivational speaker who also continued writing as well as joining his second wife administering a recreational 19th century-style baseball league, helping preserve an old ballpark (about which Bouton wrote Foul Ball), and becoming a competition ballroom dancing team. The Renaissance Bulldog.

Whenever one of Bouton’s former Ball Four-season teammates went to his reward, Bouton was genuinely saddened. “I think he came, over the years, to love them,” Kurman told Kepner. “As each one died, he got really teary about it. He realized how deeply they were part of him.” (The Pilots, of course, were sold and moved to Milwaukee for the 1970 season, becoming the Brewers. “The old Pilots are a ghost team,” Bouton once wrote, “doomed forever to circumnavigate the globe in the pages of a book.”)

Ball Four‘s true success, wrote Roger Angell himself (one more time: Angell isn’t baseball’s Homer; Homer was ancient Greece’s Roger Angell), “is Mr. Bouton himself, as a day-to-day observer, hard thinker, marvellous listener, comical critic, angry victim, and unabashed lover of a sport. What he has given us is a rare view of a highly complex public profession seen from the innermost side, along with an ironic and courageous mind. And, very likely, the funniest book of the year.”

Baseball didn’t collapse. The world didn’t implode. That Star Spangled Banner yet waves. Things have happened in baseball since that make any outrage over Ball Four resemble the kindergarten style debate most of the original hoopla really was. “If Mickey Mantle had written Ball Four,” Bouton once wrote, “it wouldn’t have been a big deal. A marginal relief pitcher on the Seattle Pilots had no business writing a book.” Or, implicitly, exposing the foibles and more of the reserve era’s abuses than anyone suspected existed within the Old Ball Game.

The marginal relief pitcher, once a Yankee World Series star, ended up meaning far more than that. If you want to call Bouton part of the conscience of baseball, then you must admit with more than a single tear that baseball lost something precious with his illness and, now, his death. So has his wife. So have their children and grandchildren. So has America. May the Lord and his beloved daughter welcome him home gently but happily.