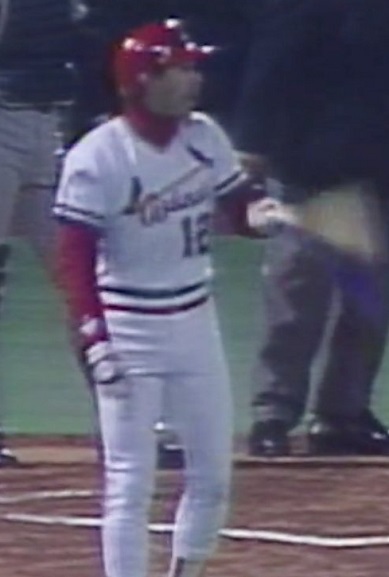

Tom Lawless, the patron saint of bat flippers, starting his flip in Game Four, 1987 World Series . . .

The Fun Police have a new protester who played the game in an earlier era. And when Dale Murphy talks, it would be wise for the Fun Police to lend him their ears and not their billy clubs.

Murphy inaugurated his partial new life writing for The Athletic with a September 2018 essay in which he applauded doing away with throwing at batters on hot streaks. That was after the Marlins’ Jose Ureña was stupid enough to think the proper way to stop Ronald Acuna, Jr. from making mincemeat out of Marlins pitching was to open a game by drilling Acuna’s elbow.

The longtime Braves bombardier said then pitching inside is one thing but drilling hitters who offend you is something else entirely. “If Ureña thought he was being tough, he wasn’t. Good pitchers–and staffs–will take command of a situation before a guy is swatting home runs left and right. The Marlins kept throwing Acuña fastballs down the middle. Well, what did they think was going to happen? A light should have gone on. Hmm, maybe we should try something else.”

Now, Murphy wasn’t exactly amused when Madison Bumgarner barked at Max Muncy after Muncy drove one of Bumgarner’s offerings clean into McCovey’s Cove last week. Murphy was far more impressed not just that Muncy was sharp enough in spontaneity to hand Bumgarner a classic one-liner (I just told him if he doesn’t want me to watch the ball, go get it out of the ocean) that begat a classic troll shirt, but that Muncy had no qualms about even a lower-keyed celebration of, you know, achievement.

“Admiring a home run is OK,” Murphy writes in an essay published Friday. “Bat-flipping is OK. Emotion is OK. None of that is a sign of poor sportsmanship or disrespect for an opponent. It’s a celebration of achievement — and doing so should not only be allowed, but encouraged.” And he’s not limiting its encouragement to hitters alone, either. “Pitchers can shout excitedly after an important out,” he writes. They can pump their fist after a clutch strikeout. Players, fans—and basically any rational-thinking human—will understand that no harm is intended by these spontaneous expressions of joy.”

Last year, Nationals reliever Sean Doolittle jumped onto the fun train. And he said he wanted more than just bat flips. “If a guy hits a home run off me, drops to his knees, pretends the bat is a bazooka, and shoots it out at the sky, I don’t give a shit,” he said. To which I myself added, “I hope a lot of pitchers start channeling their inner Dennis Eckersley and start fanning pistols after they strike someone out. I’d kill to see a hitter moonwalk around the bases after hitting one out. Let’s see more keystone combinations chest bump or make like jugglers after they turn a particularly slick and tough double play.”

“These are some of the best athletes in the world, competing against some of the other best athletes in the world, with generational wealth at stake,” writes Murphy. “Yet, they’re expected to play baseball like they’re doing calculus at afternoon tea.” My own expression was (and remains) that whereas Willie Stargell was right saying, “The umpire doesn’t say, ‘Work ball’,” if you want to play baseball like businessmen, take the field and check in at the plate in three-piece suits.

“In what other sport does this happen?” Murphy asks. “In what other sport is celebration considered disrespect? In football, guys plan celebrations. They choreograph them with teammates. They gesture when they get a first down. As far as I know, the world hasn’t ended. Baseball is a strange place. It’s not OK to watch your home run, but it is OK for someone to throw a baseball 95 miles per hour at your head if you do.”

It’s still funny in anything but a ho-ho-ho way that when it’s free agency signing season the Old School wants us to remember they’re getting overpaid to play a game, for crying out loud . . . but when it’s time to actually play the game, God forbid the players look like they’re, you know, playing.

Murphy is careful not to say that those on the field who don’t like celebrating their achievements should be allowed not to like it, either. But he’s adamant that if they want to celebrate, they shouldn’t risk being decapitated the next time they bat against the pitcher they just took into the ocean. And, to Madison Bumgarner’s eternal credit, he didn’t even think about trying to flip Max Muncy when Muncy faced him the next time.

Neither did the arguable and unlikely father of the home run bat flip as we’ve come to know it face revenge.

I take you back to the 1987 World Series. The one in which no game was won on the road and the Twins won in seven. The one in which Tom Lawless—journeyman infielder, minus 2.1 wins above a replacement-level player, lifetime .521 OPS, lifetime hitter of two regular-season major league home runs, who hadn’t hit one out since 1984—squared up Frank Viola (a Cy Young Award winner the following season) with two on and nobody out, in the bottom of the fourth, in a tied-at-one Game Four, and hit a meaty fastball over the left field fence.

Lawless took ten leisurely steps out of the box up the first base line as the ball flew out. When it banged off a railing above and behind the fence, he flipped his bat about ten feet straight up into the Busch Stadium air before starting his home run trot. The crowd may have cheered as much for that flip as for the ball flying out in the first place.

“Look at this!” hollered then-ABC commentator Tim McCarver when showing it on a replay. McCarver and Al Michaels sounded absolutely exuberant. Viola didn’t exactly look thrilled to have just surrendered a tiebreaking three run homer, but he wasn’t exactly spitting fire or raging in the moment, either.

As Bleacher Report‘s Danny Knobler observes in Unwritten: Bat Flips, the Fun Police, and Baseball’s New Future, Viola never once retaliated for the Lawless flip. On 14 May 1989, Viola and Lawless met for the first time since that Series, with Lawless now a Blue Jay pinch hitting for Rob Ducey in the top of the fifth. Viola caught Lawless looking at a third strike in that pinch hit appearance. Lawless stayed in the game playing right field, of all places. He batted against Viola in the top of the eighth and grounded out to first.

Not once did Lawless face a knockdown or brushback.

It’s a shame someone didn’t teach that lesson to Hunter Strickland two years ago, when he opened against Bryce Harper by drilling Harper in the hip—over a couple of long, almost three-year-old postseason home runs the second of which Strickland thought Harper pimped, when the only thing Harper actually did was make sure the launch straight over the right field line and foul pole would fly out fair.

“I didn’t remember flipping it,” Lawless said after that ’87 Series game. “I’ve never been in a position like this before.” He never would be again, either. That blast was the only World Series hit of Lawless’s career, and he never played in the Series again.

In 2017, he told a Cardinals television broadcast interviewer, “I don’t have any idea why I did it. It just happened.” Spoilsport.

Ring Lardner became disillusioned with baseball because of the live ball era. He wrote about it plainly in a New Yorker essay in 1930, “

Ring Lardner became disillusioned with baseball because of the live ball era. He wrote about it plainly in a New Yorker essay in 1930, “