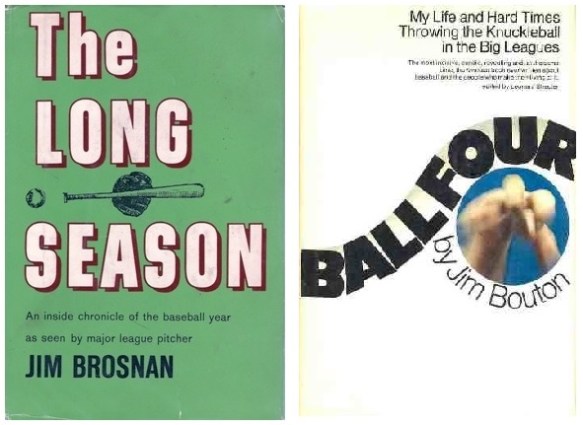

The books they said would subvert baseball. The game goes ever onward and the books never remain out of print. (So far.) Fifty years ago, Jim Bouton pitched his Ball Four season; ten years before that, Jim Brosnan pitched The Long Season.

The New York Public Library’s list of 20th century Books of the Century includes only one book pertaining to sports, Jim Bouton’s Ball Four. Yes, I was surprised, too, considering such volumes as Jim Brosnan’s The Long Season, anything by Roger Angell (one more time: he isn’t baseball’s Homer, Homer was ancient Greece’s Roger Angell), Roger Kahn’s The Boys of Summer, Bernard Malamud’s The Natural, Mark Harris’s Bang the Drum Slowly, and Arnold Hano’s A Day in the Bleachers, among others.

But there Bouton’s volume reposes, in a club to which also belong T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, Edith Wharton, Ralph Ellison, Jack Kerouac, John Dos Passos, Albert Camus, Agatha Christie, Grace Metalious, and Tom Wolfe. Before you retort that Bouton didn’t exactly write The Waste Land, Light in August, Invisible Man, On the Road, or The Bonfire of the Vanities, it’s only fair to say that Eliot, Faulkner, Ellison, Kerouac, and Wolfe never had to try sneaking a pitch past Carl Yastrzemski, Lou Brock, Harmon Killebrew, or Willie Mays, either.

Bouton was with the Astros when Ball Four was published in April 1970, after excerpts appeared in Look. To say it was received less than approvingly around baseball is to say Baltimore needed breathing treatments after the Mets flattened the Orioles four straight following a Game One loss in the 1969 World Series. “F@ck you, Shakespeare!” was Pete Rose’s review, hollered while Bouton had a rough relief outing against the Reds. All things to come considered, it was a wonder Rose knew Shakespeare wasn’t a brew served on tap at the ballpark.

This year is the fiftieth anniversary season of the one Bouton recorded for Ball Four and the sixtieth anniversary of the one animating Brosnan’s The Long Season. The books have their common ground and their distinctions, chief among the latter being that Bouton didn’t shy from detailing things even Brosnan, whose candor was considered jolting enough in its own time and place, didn’t dare to tread. If Brosnan even hinted at them, it was euphemistically. Bouton didn’t bother with euphemisms.

The two pitchers have something sadder in common, too. Brosnan suffered a stroke from which he was recovering when sepsis came manifest and caused his death in 2014 at 82, a year after his wife of 62 years died. Bouton, on the threshold of 80, suffered a stroke in 2012 that left him with cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a brain disease linked to dementia and compromised his ability to speak and write. Making it worse: the stroke occurred on the fifteenth anniversary of his daughter Laurie’s death in a New Jersey automobile accident.

Bouton’s wife, Paula Kurman, a speech therapist among other things (she has a Columbia University doctorate in interpersonal communications) who has worked with brain damaged children during her career, has worked with him carefully (“Together we make a whole person,” she once told a Society for American Baseball Research panel, to laughter that was sad as much as approving) and he has regained much of his speaking ability.

But he continues to struggle with what Kurman told Tyler Kepner of the New York Times was “a pothole syndrome: Things will seem smooth, his wit and vocabulary intact, and then there will be a sudden, unforeseen gap in his reasoning, or a concept he cannot quite grasp.”

Brosnan’s book was seeded two years before The Long Season‘s focus when he bumped into Sports Illustrated editor Bob Boyle. Having heard the bespectacled reliever had ideas about writing a book about major league baseball, Boyle suggested an article first “if something significant happens.” Brosnan turned in an essay about his trade from the Cubs to the Cardinals for veteran shortstop Alvin Dark, a trade one reporter described as the Cubs committing theft by trading “a mutt for a pedigreed pooch.”

“Loved it,” Boyle told Brosnan. “Why don’t you write a book about a whole season?” Two years later, that’s exactly what Brosnan did. He praised and needled in the same arch but honest tone, even if he did sanitize much of the vocabulary of the locker room or the dugout, as Bouton wouldn’t need to do a decade later. He showed the better and lesser sides of several players, but even his needles seemed not to come from malice aforethought.

Bouton was approached to do what became Ball Four by iconoclastic sports writer/editor Leonard Shecter, who’d previously written an in-depth profile of Bouton for Sport. Shecter proposed an in-season diary somewhat along Brosnan’s lines. “Funny you should mention that,” Bouton replied. “I’ve been taking notes.” During the 1969 season, Bouton would observe of his teammates, “My note-taking is beginning to make the natives restless.”

Brosnan offered no sense of wanting any kind of revenge for any kind of slight, in an era when players were too often slighted under a system that kept them, in essence, indentured servants. (One reviewer for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote that Brosnan’s “pot shots,” such as they were, didn’t enrage fellow players “because ballplayers didn’t read; it was so out of character, or so he said.”) Bouton was often accused of trying to settle scores, particularly about the Yankees, his former team about whom he wrote and spoke extensively enough when the occasion suggested it. All Brosnan and Bouton did was try to show baseball and its players, coaches, managers, and administrators, as a too-human game played and run with too-human foibles, follies, and fantasias alike.

The devil was really in the details and even the language in Ball Four, from neither of which Bouton shied a single step. But both pitchers were accused of a kind of insider trading for fun and profit. “Brosnan has his say about many who may have, in times past, had their say about him,” wrote Bill Veeck of The Long Season, at a time Veeck still owned the White Sox. “This just doesn’t seem to come off so well, and tends to lessen the impact and enjoyment of his undeniably colorful material.” Presumably, Veeck took his own critique to heart when writing his own Veeck—as in Wreck, which did for baseball executives’ memoiring what Brosnan and later Bouton did for players’, and what Veeck did even further with his subsequent The Hustler’s Handbook.

“As an active player on a big-league team I had seemingly taken undue advantage by recording an insider’s viewpoint on what some professional baseball players were really like,” Brosnan wrote, after The Long Season and Pennant Race (his followup, about the 1961 Reds’ unexpected National League pennant winner) were republished on the latter’s season’s fortieth anniversary. “I had, moreover, violated the idolatrous image of big leaguers who had been previously portrayed as models of modesty, loyalty and sobriety — i.e., what they were really not like. Finally, I had actually written the book by myself, thus trampling upon the tradition that a player should hire a sportswriter to do the work. I was, on these accounts, a sneak and a snob and a scab.”

Bouton got the chance to address the hoopla around Ball Four in a followup book, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take it Personally (its jacket featured a baseball with a blackened eye drawn onto the hide) which was just as funny as Ball Four and sometimes a lot more poignant. “I think it’s possible,” he wrote, “that you can view people as heroes and at the same time understand that they are people, too, imperfect, narrow sometimes, even not very good at what they do. I didn’t smash any heroes or ruin the game for anybody. You want heroes, you can have them. Heroes exist in the mind, anyway.”

Or, out of their minds, if you ponder one reaction to Ball Four. Before the Astros farmed Bouton out in 1970, Bouton discovered a burned copy of the book on the steps of the dugout, courtesy of the Padres. Even Brosnan’s and Veeck’s books avoided that kind of grotesquery.

The worst to happen to Brosnan after The Long Season and Pennant Race, not to mention other essays published in several other magazines, was the White Sox (to whom Brosnan was traded early in the 1963 season, long after Veeck sold the team) inserting a clause in his proposed 1964 contract barring him from writing for publication without prior team approval. Refusing to sign a contract with a clause like that in it, Brosnan retired after no other team took even a flyer on him, despite both Sports Illustrated and The Sporting News taking his side.

Bouton was either reviled as “a social leper” or a cancer on the game for having written and published Ball Four. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn actually tried to suppress the book, hauling Bouton into his office, demanding Bouton sign a statement saying it was all the pernicious work of his editor Shecter. Bouton probably had to restrain himself from telling Kuhn where to shove the statement when he wasn’t trying to restrain himself from laughing.

It was Dick Young of the New York Daily News who described Bouton as a social leper for writing Ball Four. When he ran into Bouton on an Astros visit to Shea Stadium, he said hello and, when Bouton needled him for talking to social lepers, Young replied, “Well, I’m glad you didn’t take it personally.” That reply gave Bouton the title of his followup book, in which he credited such overreactions in the sports press for doing almost the most to ensure Ball Four a best seller.

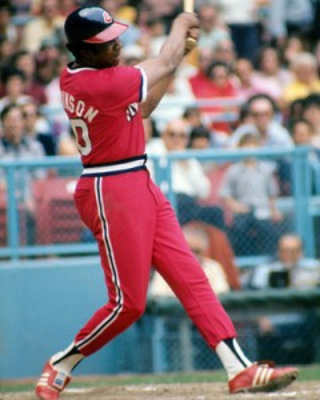

Both pitchers were witty, literate, and not even close to being thoroughgoing jocks. Brosnan made his way as a competent if mostly unspectacular relief pitcher and spot starter with a strong slider who had his moments. Bouton was a promising, hard throwing Yankee starting star, with a live fastball and a hard curve ball, until two seasons of overwork (1963 and 1964, and a whopping 520.2 innings over the two) left him with arm and shoulder trouble (it began a third of the way through 1964) that reduced him to marginal relief work and prompted him to make the knuckleball, which he’d thrown only as a change of pace previously, his bread and butter pitch.

Brosnan kept so many books in his locker that his 1961 Reds teammate, Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, nicknamed him the Professor. Bouton was no less literate or cerebral, though he may not have had a locker library equal to Brosnan’s, but his early ferocity as a competitor (he was once famous for his cap falling off his head as he delivered) inspired New York Post writer Maury Allen to nickname him Bulldog.

But Bouton may have put baseball into perspective even more than Brosnan did. Both pitchers were very aware of the worlds around them, and both wrote about the periodic spells of boredom, racial tensions, off-field skirt chasings, and self-doubts endemic in their professional baseball lives. Brosnan saved them for his books and articles; Bouton was less reluctant to speak his mind about things like politics, Vietnam, and civil rights when asked or when a conversation left him the opening.

Bouton bought even less into the still-lingering press representations of athletes as heroes. Teammates didn’t always hold with that or other things, like calling them out on it when they made mistakes that cost the Yankees games he pitched.

“After two or three years of playing with guys like [Mickey] Mantle and [Roger] Maris,” he wrote in I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, “I was no longer awed. I started to look at those guys as people and I didn’t like what I saw. They were fine as baseball heroes. As men they were not quite so successful. At the same time I guess I started to rub a lot of people the wrong way. Instead of being a funny rookie, I was a veteran wise guy. I reached the point where I would argue to support my opinion and that didn’t go down too well either.”

“He stands out,” Shecter wrote of Bouton in Sport, “because he is a decent young man in a game which does not recognize decency as valuable.” Much the same thing was said of Brosnan no matter what particular writers did or didn’t think of his two books.

Brosnan’s post baseball life including writing, advertising work (he’d done it in the offseasons of his pitching career), occasional sportscasting, and raising his family in the same Illinois home he bought with his wife, Anne, in 1956. (When they married, one local story’s headline, referencing his wife’s maiden name, said, “Pitcher Marries Pitcher.”)

Bouton became a sports anchor for New York ABC and then CBS before trying a baseball comeback in the White Sox system and then with the independent (some say notorious) Portland Mavericks, a comeback that ended with getting five starts for the Braves in late 1978. In one of those starts, Bouton squared off against Astros legend J.R. Richard, on the same night Richard broke the National League single-season strikeout record for righthanders, and pitched Richard to a draw. “The young flamethrower against the old junkballer,” Bouton wrote of the game.

A concoction Bouton and Mavericks teammate Rob Nelson invented in the bullpen, shredding gum into strands similar to chewing tobacco, became a hit as Big League Chew when they sold the idea to Wrigley. Bouton also continued writing, became a motivational speaker, and survived the collapse of his first marriage to meet and marry Kurman, blending two families, becoming founders and leaders of a recreational baseball league playing by 19th century rules, and becoming competition ballroom dancers. The Renaissance Bulldog.

The Washington Post‘s distinguished literary critic Jonathan Yardley wrote of The Long Season that it was literature about “[a]n ordinary season — life as it’s really lived — rather than an extraordinary one.” You could say, then, that Pennant Race was literature about an extraordinary season lived and played by ordinary men, if you don’t count Frank Robinson. Ball Four, which ran more temperatures higher up scales than Brosnan could claim, could be called an ordinary season lived and played by ordinary men. Recorded by a man whose extraordinary side was eroded by injuries.

Bouton may have hit the true key as to why all three books also unnerved baseball and its assorted establishments. “If Mickey Mantle had written Ball Four,” he later remembered, “it wouldn’t have been a big deal. A marginal relief pitcher on the Seattle Pilots had no business writing a book.” Likewise, if Robinson or Stan Musial had written The Long Season (Brosnan began 1959 with the Cardinals but was traded to the Reds midway) instead of a middle relief pitcher, it might not have proven a big deal.

Brosnan’s and Bouton’s books became baseball classics (as did Veeck—as in Wreck), and Ball Four also helped further expose the abuses heaped on players by front offices before the end of the reserve clause but probably caused no few of its younger readers to become sports journalists themselves. One suspects even now that Bouton’s revelations about the one-sided contract negotiations to which reserve era players were subject might have infuriated the purists more than his revelations about players’ sex drives, amphetamine indulgences, pranks, and feuds did.

Whenever one of Bouton’s former Ball Four-season teammates goes to his reward, Bouton is genuinely saddened. “I think he came, over the years, to love them,” Kurman told Kepner. “As each one died, he got really teary about it. He realized how deeply they were part of him.” (The Pilots, of course, were sold and moved to Milwaukee for the 1970 season, becoming the Brewers. Writing in Ball Four Plus Ball Five, a tenth-anniversary update, Bouton said, “The old Pilots are a ghost team, doomed forever to circumnavigate the globe in the pages of a book.”)

The Long Season remains “a cocky book, caustic and candid and, in a way, courageous, for Brosnan calls him like he sees them, doesn’t hesitate to name names, and employs ridicule like a stiletto,” as wrote Red Smith, arguably the best baseball writer in New York (then with the Herald-Tribune).

Ball Four‘s true success, wrote Roger Angell himself, “is Mr. Bouton himself, as a day-to-day observer, hard thinker, marvellous listener, comical critic, angry victim, and unabashed lover of a sport. What he has given us is a rare view of a highly complex public profession seen from the innermost side, along with an ironic and courageous mind. And, very likely, the funniest book of the year.”

And in the long, long, long wake of Brosnan’s and Bouton’s books, baseball hasn’t collapsed, the world hasn’t imploded, that Star Spangled Banner yet waves, and men and women of note or fame can be considered in all their human flaws, foibles, and fantasias, without being seen where appropriate as any less than heroes.