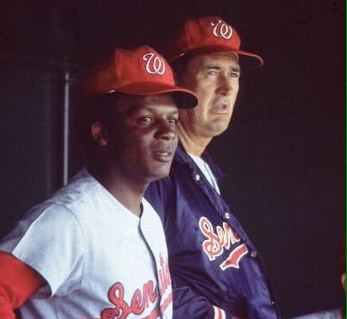

Albert Pujols just after hitting the home run tying him with Willie Mays on the career list Sunday.

A little earlier this pandemic season, Albert Pujols received a text message on his cell phone. “It’s your time now. Go get it,” the message said. The message came from Hall of Famer Willie Mays, whose 660 lifetime major league home runs Pujols has chased all season long.

With the shadows creeping in in the top of the eighth at Coors Canaveral Sunday afternoon, Pujols went and got it. With his Los Angeles Angels down 3-2 and a man on first, El Hombre turned on a meaty 1-1 fastball from Rockies reliever Carlos Estevez and drove it parabolically down the left field line and halfway up the seats.

The blast was the kind of launch for which Pujols has been fabled from the moment he first came into his own in St. Louis almost two decades ago. The kind he’s hit the last few years almost to the exclusion of anything else.

The kind that reminds you of both the greatness that will punch his Cooperstown ticket and the greatness that’s been eroded by the injuries that have sapped him since after his first season as an Angel, turning his ten-year, $255 million contract into the unfair poster child for terrible sports contracts.

When Pujols commented after Sunday night’s game, it was tough to know which affected him more, finally meeting Mays in the record book or Mays himself urging him on in the first place. “Legend,” said the agreeable Dominican who was born seven years after Mays played his last major league game. “I mean, it’s unbelievable.”

Oh, it was believable, all right. Pujols’s swing remains a work of art, even if it’s supported by legs that betrayed him almost a decade ago, a knee that underwent a surgery here and there, a heel that fought with painful plantaar fascitis costing him the final two months of 2013, feet requiring surgeries after 2015 and 2016.

“When his days are done and his legend is told,” wrote The Athletic‘s Fabian Ardaya, shortly after Pujols’s milestone blast, “they will talk about the swing — that beautiful, powerful swing — and the follow-through and the strut when you knew, everyone knew, that Albert Pujols got every piece of a baseball.”

The swing cemented Pujols as perhaps the best right-handed hitter the game has ever seen. It is slower now, a reality that happens with age, and the majestic drives don’t occur as often. But when they do, even for a split second, they take you back to when Pujols wrecked the league, ruined historic closer seasons and, quite simply, hit.

They take you back to when the only thing keeping Pujols’s three-run detonation against Brad Lidge inside Minute Maid Park in the top of the ninth, 2005 National League Championship Series, was the bracing for the park’s retractable roof. The bad news: that bomb won the Game Six battle but merely saved his Cardinals from losing the war in Game Seven.

They take you back to when Pujols ripped three in a kind of reverse cycle in Game Three of the 2011 World Series—a three-run blast, a two-run blast, a solo blast, in that order, and every one of them after the sixth inning in a 16-7 demolition of the Texas Rangers. The solo provided the sixteenth run.

They take you back to when Pujols was younger, unimpeded by his lower body health, and liable to either drop Big Boy or otherwise make life miserable for opposing pitchers and fielders, in a St. Louis run that left him as the Cardinals’ second-best all-around position player ever, behind the man on behalf of whom Pujols doesn’t always accept having been nicknamed El Hombre.

They take you to his deadly postseason record—the lifetime postseason .323/.431/.599 slash line; the .725 lifetime postseason real batting average (RBA: total bases plus walks plus intentional walks plus sacrifice flies plus hit by pitches divided by total plate appearances); the 109 runs produced. Enough Hall of Famers don’t look half that dangerous playing for all the platinum.

Two years ago Pujols tied Hall of Famer Stan Musial on the all-time runs batted in list. Five years before that, when Musial died, Pujols was almost inconsolable. He and Musial became that close personally. “I know the fans call me El Hombre, which means The Man in Spanish,” he insisted, “but for me and St. Louis there will always be only one Man.”

So insistent on the point was Pujols that, when he became an Angel and the club began hoisting billboards touting El Hombre‘s arrival, Pujols flipped. He insisted very publicly there was only one player who should ever be called The Man, and it wasn’t Albert Pujols. The billboards disappeared faster than the Angels executed their scouting staff after an international signing scandal.

When Pujols talks about his own place in baseball, he does it almost as though the idea that he’s part of it is secondary to what came before him. “I know my place in history,” he told Ardaya. “(But) it’s hard. I don’t want to — It’s almost like I take it personal, like I don’t want to disrespect this game.”

He’s even ready to hand history off to the teammate who played his first full season in an Angel uniform the same year Pujols joined the team. The teammate who’s now the Angels’ all-time franchise home run leader and has been the game’s all-everything player almost right out of the chute. The teammate who doesn’t have a team baseball’s All-Universe player can be proud of.

“We have the best player in the game,” Pujols told Ardaya of Mike Trout, “and five or six years from now, he’s going to be making history, too.” As if he hasn’t already. Pujols knows it.

You think that’s an affectation? Pujols is the same player who refused to join the ruckus in Detroit last year, when he hit one out in Comerica Park for his 2,000th career RBI and, for whatever perverse reasons, MLB and the Tigers together tried to strong-arm the Tiger fan who caught the ball by refusing to authenticate it, until or unless he turned it over, assuming before asking that he wanted to cash the ball in big.

Ely Hydes didn’t like being treated like an opportunist. “Honestly, if they were just cool about it I would’ve just given them the ball,” Hydes told a WXYT interviewer. “I don’t want money off of this, I was offered five and ten thousand dollars as I walked out of the stadium, I swear to God . . . I just couldn’t take being treated like a garbage bag for catching a baseball.”

Pujols understood. Completely. “Just let him have it, I think he can have a great piece of history with him, you know,” he said. “When he look at the ball he can remember . . . this game, and I don’t fight about it. You know, I think we play this game for the fans too and if they want to keep it, I think they have a right to. I just hope, you know, that he can enjoy it . . . He can have it . . . He can have that piece of history. It’s for the fans, you know, that we play for.”

Hydes eventually gave the ball to the Hall of Fame in memory of his little son who died at 21 months old a year before Daddy caught the Pujols milestone.

Mays finished his career both with 660 home runs and as a shell of his once-formidable self, ground down by all those seasons and no few off-field heartbreaks, unable until his body finally put him in a stranglehold to admit that the game he loved and lived to play was no longer fun when he was Willie Mays in name only.

Those were real tears that almost poured out of Mays when he faced a Shea Stadium throng on Willie Mays Day, with the Mets who brought him back to the city of his major league youth, and told them, “There always comes a time for someone to get out. And I look at these kids over there, the way they are playing, and the way they are fighting for themselves, and it tells me one thing: Willie, say goodbye to America.”

It shouldn’t shock anyone when Pujols’s time finally arrives. You can say his time is past, that his lower body ruined what should have been a simpler, kinder, gentler decline phase, leaving him prone to as much criticism under ordinary circumstances as praise when now and then the vintage edition makes a cameo as it did Sunday night.

You should also say, as Angels general manager Billy Eppler did two years ago, that few really knew, never mind understood, Pujols’s determination to play through every lower-body malady he’s incurred since trading Cardinal for Angel red.

“He plays through discomfort,” Eppler told MLB.com. “He endures a lot and doesn’t talk a lot about it. But I can tell you that he’s definitely someone that wants to play and fights through a lot of adversity to make sure he’s out there and contributing to the club.”

There’s something to be said for that as well as against that. It’s not as though Pujols needed to burnish his Hall of Fame resume. And, it’s not as though the Angels couldn’t have cashed him in for things they needed even more than they needed Pujols’s cachet—things like a pitching overhaul, mostly.

He has one more year to go on his Angels deal. The Angels as they stand now are still going nowhere and they still need a radical pitching overhaul if they have any prayer of returning to competitive greatness, with Trout committed to them for life and Pujols knowing he can tell Father Time to go to hell only so much longer, if at all.

Would the Angels even think of trading Pujols this offseason, to a contender with young pitching talent to spare, in need of a veteran mentor to whom they’d be grateful for all his counsel and whatever hits he has left, before the Angels bring him back for that ten-year personal services deal that begins when his playing days end? Who knows?

Such a team could do a lot worse than drawing counsel from the man whom Baseball-Reference lists as the number two first baseman ever to play the game. Only Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is ahead of him. But Pujols has an arguable case as the greatest all-around first baseman of all time simply because, as devastating as he’s been a hitter, he was also a far better defensive first baseman than Gehrig before his lower body resigned its commission.

Or, maybe, Pujols himself will take stock, surrender to his body’s and Father Time’s mandate at last, leave next year’s $30 million on the table, start that personal services term, and congratulate himself as baseball should on a one-of-a-kind playing career. Maybe. Only Pujols knows for certain, and he doesn’t seem to like talking about that any more than he liked talking about what it took for him to just stroll up to the plate any more.

Maybe the combination of this year’s pandemic surreality and the current major league regime’s continuing inability to promote its best and give proper due to its milestoners kept Pujols’s Sunday night smash hit from blowing the social media universe up too much beyond about an hour’s worth of ordnance.

“To be able to have my name in the sentence with Willie Mays is unbelievable,” Pujols said Sunday night. The Angels have an off-day Monday. He hasn’t hit well this season, and Sunday’s smash was only his fourth home run in 31 games. One homer every seven games on average. He and they have twelve games left.

All Pujols needs is one more meaty pitch to drive, one more summoning up of whatever remains of that impeccable swing, and they’ll be saying his name in the same sentence as Mays once again. This time, for passing him to become sole possessor of number four on the all-time bomb squad.

Maybe then, he’ll get the twenty-one guns he deserves. Maybe.

When all was said and finally done, Marvin Miller got what he no longer wanted. He’d said it expressly and pointedly enough, citing specifically the assorted Veterans Committees he believed with certain merit were often enough stacked for certain results. “At the age of 91,” he said, “I can do without farce.”

When all was said and finally done, Marvin Miller got what he no longer wanted. He’d said it expressly and pointedly enough, citing specifically the assorted Veterans Committees he believed with certain merit were often enough stacked for certain results. “At the age of 91,” he said, “I can do without farce.”