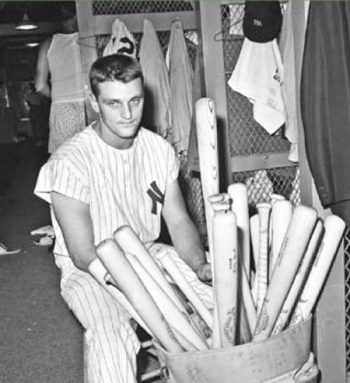

Roger Maris in the Yankee clubhouse, 30 September 1961—the day before he swung his way into history.

Bad enough when I spot those in the baseball press I don’t know personally but perpetuate mythology over factuality. But now my editor at the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America’s Here’s the Pitch newsletter, a man who’s become a friend in the bargain, does it.

Pondering Aaron Judge’s choice of number 99 on his Yankee uniform, Dan Schlossberg writes in today’s HTP, “Perhaps he knew he would become twice as good as [Roger] Maris? Certainly, Maris never chased a Triple Crown. In fact, his .260 lifetime batting average is the leading negative whenever his Hall of Fame candidacy is considered.”

Not even close, my good friend.

Mike Schmidt hit only seven points higher than Maris lifetime and that didn’t stop his election to the Hall of Fame. OK, that’s a ringer. Schmidt is the arguable greatest all-around third baseman ever to play the game. But his lifetime .267 hitting average didn’t exactly block him from Cooperstown, either.

There are lots of Hall of Fame players who hit in the .260-.269 range lifetime. Those modest hitting averages didn’t block them, either. They had other factors in their favour. And so might have Roger Maris except for one pair of problems.

Problem one: Maris was so badly seared by his pursuit and breaking of ruthsrecord in 1961 that there were times too many writers of the time believed he began to shy away from perpetuating the greatness that was his for the taking. Never permitted to enjoy truly the blessings of having cracked baseball’s single most prestigious record, Maris looked from there like a man to whom greatness was an intruder, not a companion.

Problem two: After a solid 1962 season, the injury bug began to hit Maris. Back trouble limited him to ninety games in 1963. He had a bounceback 1964, with 26 home runs, despite missing twenty games with assorted leg injuries. Then came 1965 and the injury that should have proved scandalous for the manner in which the Yankees handled it.

First, Maris suffered a pulled hamstring that kept him out 26 games after the first three weeks of the 1965 season. Then, come 20 June, Maris jammed his hand against the plate umpire’s shin guard while sliding home. He tried playing a few after that, but the injury was severe enough to take him out of the second game of a doubleheader against the Kansas City Athletics and out of the Yankee lineup after 28 June.

Finally the hand injury was diagnosed as bone chips for which he underwent offseason surgery. It turned out to be far worse. The hand continued to bother him as he started 1966. At last he complained about the problem, and all that did was crank the New York sports press that never truly accepted him and the Yankees themselves into harrumphing that he had no business complaining.

The hand injury turned out to have been a misdiagnosed fracture. Whatever remained of his once-formidable home run power was gone. So was Maris’s desire to continue playing. He’d played through enough injuries as it was and felt unappreciated for the effort. The Yankees aged profoundly during and after 1964, the final pennant winner of the old Yankee guard, but the Yankees needed the Maris, Mickey Mantle, and Whitey Ford box office more than they needed them properly healthy, so it seemed in retrospect.

The writers chose Maris as the primary culprit, often accusing him of loafing, as some teammates did, both of whose sides were unaware of the true severity of the hand injury. If you’re looking for evidence as to why other players become either paranoid or hypochondriacal about their physical health, Maris was key evidence on their behalf.

“For those who had refused to appreciate Maris in the early 1960s,” wrote his Society for American Baseball Research biographer Bill Pruden, “his injury-plagued performance in the middle part of the decade, coming when the Yankees as a team were faltering, only seemed to confirm their views.”

For a man who had never placed any individual accomplishment above winning, it was a difficult time. Indeed, tired of battling injuries, of trying to play, even when hurt, but never seeming to be appreciated for the effort regardless, Maris gave much thought to retirement. However, before that decision could be made, the struggling Yankees traded Maris to the St. Louis Cardinals for third baseman Charley Smith.

Maris continued to play a solid right field in St. Louis for two consecutive pennant winners and their 1967 World Series champions (he also had the best Series of his career individually), before retiring at last and accepting Cardinal owner Gussie Busch’s offer to operate a Budweiser beer distributorship in southern Florida. He throve in the business with his brother Rudy as his partner, until he succumbed to lymphoma at 51 in 1985.

Injuries, not indifference or loafing, put paid to Maris’s Hall of Fame case before he had the chance to solidify one following his Hall-caliber 1960-62 seasons. Meanwhile, my friend Schlossberg went on to write, “Maris batted just .269 [in 1961] against expansion-diluted pitching.” Halt right there, Daniel.

The fear of diluted pitching when the American League expanded for the first time was probably one of the factors animating commissioner Ford Frick’s scurrilous conflict-of-interest bid to deny anyone, Maris or otherwise, legitimacy in pursuing ruthsrecord in 1961. Well, now. Would you like to know how “diluted” the league’s pitching actually became?

I know I sure did. And I found out. Pay very close attention to the following table, showing the league’s 1960 and 1961 earned run averages, fielding-independent pitching rates, walks and hits per inning pitched, strikeouts per nine innings, and walks per nine.

| AL Pitching | ERA | FIP | WHIP | K/9 | BB/9 |

| 1960 | 3.87 | 4.00 | 1.37 | 4.9 | 3.6 |

| 1961 | 4.53 | 4.09 | 1.38 | 5.2 | 3.7 |

There was a 66 point jump in the league’s ERA for 1961, well enough shy of a full run’s difference. But look further and closer. That’s not the place you end pondering the difference in the league’s pitching from ’60 to ’61, it’s the place where you only begin.

The league’s FIP—measuring that for which pitchers alone are responsible (you can call it their ERA without their fielders’ performances factored in) remained practically the same, unless you think a mere nine-point rise is equivalent to scaling the Empire State Building.

AL pitchers also averaged a lousy single point more walks and hits per inning pitched (WHIP) in ’61 than in ’60. They struck out practically the same average per nine innings and walked almost exactly the same per nine. If that’s drastically “diluted” pitching, I’m a dead bolt.

If anything, Maris had a tougher time hitting 61 in ’61 than the Sacred Babe had in 1927. I’ve noted it before but it’s worth nothing again here: The advent of relief pitching above and beyond being the final repose of pitchers who couldn’t cut it as starters had a big say in it.

Ruth in ’27 faced 67 pitchers all season long, while Maris in ’61 faced 101. Ruth got to face pitchers a third time around in games 35 percent of the time in ’27; Maris enjoyed that privilege only 30 percent. He faced more fresh arms in games than Ruth did.

Did I mention again, too, that this year Aaron Judge faced 232 pitchers by the end of the doubleheader during which he hit his 55th home run of the year? That he faced pitchers a third time around in only seventeen percent of his games as of the end of that twin bill?

The myth of diluted AL pitching in 1961 isn’t quite as grave as the truly unconscionable myth of The Asterisk, of course. But it has in common with that disgrace that it never truly existed in the first place.

You’re welcome, Dan.