Yes, this year’s cover boy is Cal Raleigh. (And, yes, alas, Raleigh still wears the hideous nickname “the Big Dumper.”)

Well. Spring training is entering full swing, if you’ll pardon the expression. We like to think it’s as the poets and the pundits alike have enunciated time and again, the early acts producing the new birth, of spring by the calendar and by baseball season.

We’d rather not be sobered up until the first disgruntled fan of the White Sox, the Reds, the Rockies, the Angels, the Marlins, or the Mets pronounces the season to come lost upon one bad inning . . . on Opening Day.

The editors of Ron Shandler’s 2026 Baseball Forecaster & Encyclopedia of Fanalytics, alas, hew to the truth that facts don’t care about your feelings. (“Fanalytics” is their compound of fantasy and analytics.) They also uphold the truth that the only crime in information behind, beyond, and beneath the surfaces is rejecting it.

Whether you’re a fan, fantasy ballplayer, sportswriter, player, coach, manager, player agent, or front office muckety-muck, ignorance isn’t bliss.

This fortieth edition of Baseball Forecaster (Mr. Shandler birthed it the last year his beloved Mets won a World Series) contains what the old and very much missed Elias Baseball Analyst once contained: the most important information for Americans to master this side of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and The Federalist Papers.

Shandler himself fires the opening high hard one after a brief anti-soliloquy regarding “Casey at the Bat” in which Mighty Casey’s descendants remain ascendant but his conqueror may be one pitch from disaster. Not the kind that flies over the fence, either: Oh here where hearts are heavy, and fans are homeward bound/The infield shouts in triumph, but there’s silence from the mound/The pitcher grabs his elbow, his face white as a ghost/Casey may have struck out, but our ace’s arm is toast.

Just in case you hadn’t taken the point, deciding Mr. Shandler tastes best when served up on the short end of a long stick, he has the temerity to point out that the number of major league pitchers who can throw past 95 miles per hour has risen from 64 in 2014 to 163 in 2024. And, the number of days pitchers spent on injured lists rose from 20,014 in 2014 to 32,250 in 2024.

Concurrently, Mr. Shandler obseves, the eight full seasons ending last October “have been an unprecedented era of record-breaking offensive performances. The new rules introduced in 2023—pitch clock, shift restrictions, larger bases, etc.—amped things up, but you can detect a subtle tipping point when hitters started making headlines even earlier.” (Italics in the original.)

The more detailed timeline Mr. Shandler sketches only begins with the team then known as the Indians including pitchers who set a new single-season major league team strikeout record in 2014. (The number: 1,450; or, eight more pitching strikeouts than that year’s Astros hitters recorded at the plate.)

Three years later, the Show set a single-season home run record. (6,105.) One year after that, major league batters struck out more than they hit safely. Don’t faint; the difference between the hits and the strikeouts was . . . 189. Or, three strikeouts fewer than ill-fated Orioles first baseman Chris Davis had at the plate that season.

One year after that, in 2019, the entire Show set a new single-season home run record (6,776) and Pete Alonso, the National League’s Rookie of the Year, set the rookie home run record. (53.) Two years later, Shohei Ohtani went nuclear: 46 home runs at the plate; a 3.18 ERA with 156 strikeouts on the mound. (Ohtani also led the Show with eight triples.)

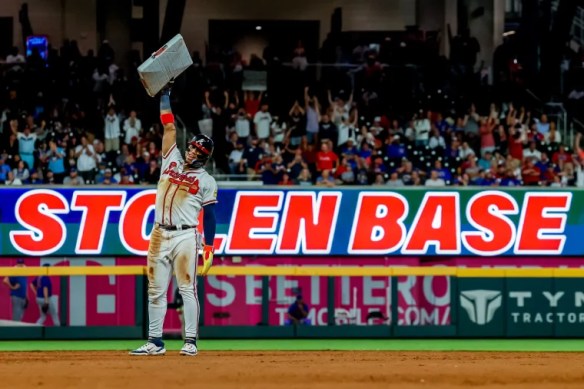

What happened in the four seasons to follow? 2022: Aaron Judge broke Roger Maris’s American League home run record. (62.) 2023: Ronald Acuña, Jr. delivered baseball’s first 40/70 (home runs/stolen bases) season. 2024: Ohtani delivered its first 50/50 season and was the fastest to hit 40/40 en route. 2025: Cal Raleigh’s 60 home runs set single-season records for catchers (he only hit 49 while in the game as a catcher, but it was still enough to eclipse Hall of Famer Johnny Bench) and switch-hitters.

But 2025 didn’t stop there, either. Ohtani became only the sixth with back-to-back 50+ home run seasons. (Mr. Shandler notes four of the other five did it during the era of actual or alleged performance-enhancing substances and the fifth was a fossil named Ruth.) The year was also the first without no-hitters since 2005, and the Mets and the Braves set new Show records for using the most pitchers. (46.)

“[C]onsidering all [that],” Mr. Shandler writes,

I can’t escape one unavoidable conclusion:

MLB must view the destruction of pitchers’ arms as acceptable collateral damage for boosting offense and fan-friendly record chases. Pitchers are fungible, like the $1 players [fantasy baseballers] draft after Round 20. There are hundreds more arms available throughout the minors, after all. Yes, they are less skilled, but that only helps increase offense even more. It’s a win-win.

Unless you’re a pitcher. (Italics in the original.)

Baseball Forecaster includes a section of “Research Abstracts,” perhaps prime among them orthopedist Dr. James C. Ferretti addressing that recent spike in pitching injuries. He acknowledges the chase for speed is its major cause but advises there’s more to the story and analyses accordingly. Hint to Joe and Jane Fan and Old Coach Cup: Don’t think the ulnar collateral ligament just blows out, and don’t assume it’s only the hardest throw that does it.

Mr. Shandler and company deliver an “Encyclopedia of Fanalytics,” which divides into five portions: Fundamentals, Batters, Pitchers, Prospects, and Gaming. In the first portion, their performance validation criteria is instructive. It’s an attempt to determine whether Thumper O’Thrasher at the plate or Slingshot D. Stonegrinder on the mound post stats that reflect their skills accurately. It combines age, health, minor league background, his historical trends, ballpark effects, team chemistry effect, batting or pitching style, usage patterns, coaching effects or lack thereof, off-season life (Has the player spent the winter frequenting workout rooms or banquet tables?), and personal factors.

Don’t laugh or sharpen your nastygram pens just yet. Never discount a player’s personal life affecting his baseball play. Dig deep as you’re allowed and you’ll find any number of players whose seasons were compromised if not ruined by family crises. (Dig deeper and you may not want to know or stomach those whose seasons if not careers were ruined by their inability to reject domestic violence.)

Back to the health factors for a moment or three. Call this the “Watch Your Language” department. Especially when you hear a report on an injured player say, “No structural damage.” Mr. Shandler and company knock that one down the line: “[It] sounds reassuring, but it’s often misleading . . . it’s a way of saying that whatever body part being imaged is intact, with no broken bone or soft tissue tear. This is not the same as a ‘normal” or “negative’ diagnosis. When you hear ‘no structural damage,’ continue to keep a close eye on the situation.”

Wait until you get to their breakdown, “Paradoxes and Conundrums.” Read carefully and defy yourself to think to yourself that a good many sportswriters and no few team officials don’t talk through their chapeaus or see with their mouths: Play hurt, take statistical dive, risk your job; admit you’re hurt, leave the lineup or the rotation to recover, and . . . risk your job.

The crew also isolate what they consider three paths to a player’s retirement: the George Brett (you’re still producing and the fans still adore you), the Steve Carlton (you stayed too long, your numbers are toxic, and nobody remembers when you were top of the heap), and the Johan Santana. (You’re on the injured list so long your retirement flies past “until your name shows up on a Hall of Fame ballot.”)

Meanwhile, the news gets worse instead of better for Emmanuel Clase. The nearly thirty-page indictment against him unsealed Friday says he got a text message reading, “Throw a rock at the first rooster in today’s fight.” It wasn’t Warner Bros. Animation telling him how they wanted him to open a new Foghorn Leghorn cartoon.

“Yes, of course, that’s an easy toss to that rooster,” the indictment says Clase replied. Translation: The beneficiary of one of his rigged pitches in an interleague game against the Reds last May had a bet on Clase throwing it low. This revelation is part of a broadening picture of the federal case that includes charges of Clase rigging a pitch or two in 2024, including during Game One of the Guards’s American League division series against the Tigers.

Shandler and company note that Clase’s hits per ball in play and stranded runner rate regressed in 2025, but other than a drop in ground ball pitches and “save” opportunities, “it was mostly business as usual through” before his pitch-rigging scandal broke. Mostly.

“But then,” they continue, “it turned out his business was anything but usual—and in fact, was allegedly illegal. Indicted in a sports betting case in November, it’s very likely this will be his final box in this book.” The promise of Baseball Forecaster‘s continuance is far more appealing than the promise of Clase’s final punishment if he graduates from alleged to absolute pitch-rigger for fun and microbetting profit.