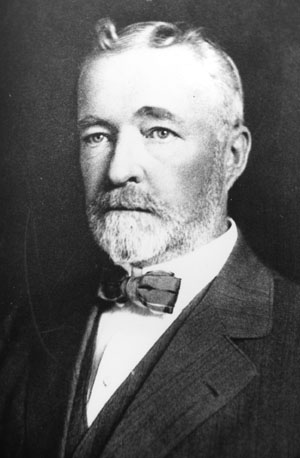

Today was supposed to see pitchers and catchers reporting to start spring training. There went that idea, thanks to the owners and their Pinocchio. (CBS Sports photo.)

Say what you will about the Major League Baseball Players Association, but they haven’t pleaded poverty yet at all, never mind with the thought that they could say it without their noses growing. On the day pitchers and catchers would have reported to spring training but for the owners’ lockout, a five-day old lie by commissioner Rob Manfred still rattles through baseball’s sounds of silence.

George Burns once said of his logically illogical wife Gracie Allen, “All I had to do was ask, ‘Gracie, how’s your brother,’ and she talked for 38 years.” All you have to do is ask a question, and Manfred will talk out of so many corners of his mouth you’ll suspect it resembles a martial arts throwing star, while his nose grows long enough to cross the Verrazano Narrows Bridge.

Last Thursday, as an owners meeting concluded, somebody asked Manfred whether owning a baseball team was a sound investment. All Commissioner Pinocchio had to do was speak what’s not exactly a badly kept secret. He chose to play the poverty card, as the owners often enough have done during baseball labour disputes. This time, however, the joker in the deck isn’t very funny

“If you look at the purchase price of franchises,” Manfred began, citing what he’d been told by investment bankers without identifying just whom, “the cash that’s put in during the period of ownership and then what they’ve sold for, historically, the return on those investments is below what you’d get in the stock market, what you’d expect to get in the stock market, with a lot more risk.”

Hello, darkness, my old friend.

Commissioner Pinocchio knows very well that baseball franchises, even those mired out of the races and even those accused plausibly of tanking, increase in value as investments up to ten percent annually. Yahoo! Sports writer Hannah Keyser wasn’t going to let him get away with that kind of lie.

“Let’s get something out of the way: The owners cried poor during the negotiations to start the pandemic-suspended season in 2020 to justify demands that the players take a pay cut,” Keyser began.

And although the owners have been quieter about it during the current collective bargaining negotiations, the implicit entrenched position is the same — on the broadest scale, they don’t want to make all the economic concessions that the union is asking for and one of the reasons they’re citing is that they can scarcely afford it.

That’s why Manfred said what he did. It’s not that he’s stupid (he’s just hoping you are) or confused. It’s strategic. To concede on the record that the current economic system is working fabulously for owners—and increasingly so in recent years—would be chum to a union that’s angry, energized and determined to push the pendulum in the other direction.

Baseball and other sports teams’ owners, according to ProPublica, whom Keyser cited, and who managed to get IRS records to probe, “frequently report incomes for their teams that are millions below their real-world earnings, according to the tax records, previously leaked team financial records, and interviews with experts.” Tax code provisions and creative amortization use, Keyser noted, “allows owners to negate gains or claim losses, substantially reducing their tax obligations and saving them millions of dollars.”

If you still believe baseball’s owners are really going broke, that Antarctican beach club for sale is now a couple of hundred thousand less expensive. They want to continue playing the poverty card despite it being about as legitimate as Astrogate? Here’s what the players should say in return: nothing. Not one proposal, not one further concession, not even a syllable, until the owners open their books completely, honestly, and without further smoke blowing, sand throwing, or shuck jiving.

It wasn’t the players who elected to strike over the owners’ three-card monte games this time. There wasn’t any legitimate reason for the owners to lock the players out after the CBA expired instead of letting the game carry forth while they sat down to honest negotiations.

Fair play: the players aren’t exactly without dubious issues. Their proposal for a mere twelve-team postseason instead of the owners’ reputed push for a fourteen-team postseason is still an idea whose time should be put out of its misery. The already-expanded postseason has diluted championship meaning and created saturation to the point where the World Series becomes a burden to watch for too many fans, not the penultimate baseball pleasure.

The seeming sounds of silence thus far on Manfred’s shameful insistence that minor league spring campers remain unpaid because the “life skills” they gain is more important than earning their keep is deafening.

So are the continuing sounds of silence on redressing what their late union leader Michael Weiner only began to redress, the now-525 pre-1980, short-career major leaguers denied pensions in the 1980 re-alignment. Weiner plus then-commissioner Bud Selig gained those players $625 per 43 games’ major league roster time, up to $10,000 a year, in 2011.

The bad news further is that they can’t pass those monies on to their families should they pass away before collecting their final such dollars. Nor did they receive any cost-of-living adjustment in the last CBA. No less than Marvin Miller himself subsequently said the 1980 pension freeze-out for them was his biggest regret. Weiner at least began a proper redress.

But when Commissioner Pinocchio and his employers the owners look you in the eye and claim owning a baseball team isn’t profitable, you should be very tempted to demand polygraphs, if not sobriety tests.

“Do you know how else I know Manfred isn’t telling the truth?” Keyser asks, before answering. “Because if he were, he wouldn’t be a very good commissioner. If it was true, he would be failing in his de facto fiduciary duty to the owners. Say what you will about Bud Selig, but under his commissionership, team valuations skyrocketed. He made being a baseball owner into a very lucrative proposition. So Manfred is saying that during his reign, that has ceased to be the case. Or he’s lying.”

Once upon a time, a Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher caught by his wife en flagrante with a woman other than said wife ran down the stairs, pointed upward to where he’d been caught, and said, “It wasn’t me!” It’s not exactly unrealistic to suggest the owners and their wooden puppet are that kind of honest.