Even now it’s impossible to see discussions of Mickey Mantle without unfair laments over what the Hall of Famer wasn’t.

It’s almost three decades since Mickey Mantle’s death and it is a half century since he was elected to the Hall of Fame. Wouldn’t you think by now that the lamentations over what could have been, should have been, would have been, might have have been for Mantle had ceased and desisted? Isn’t what been been far more than enough?

Could have been one of the truly greats. Never quite lived up to his potential. Squandered so much of his enormous talent. Variations on those themes and more. All patent nonsense. I began getting that a-ha! when reading Allen Barra’s 2002 book, Clearing the Bases: The Greatest Baseball Debates of the Last Century.

Barra devoted a chapter to an in-depth comparison between Mantle and his transcendent contemporary Hall of Famer Willie Mays. Near the end of it, he ran down the foregoing laments, sort of, then asked, “But what about what Mantle did do?” to finish the chapter:

We spent so much of Mantle’s career judging him from [his longtime manager] Casey Stengel’s* perception as the moody, self-destructive phenom who never mastered his demons, and we spent much of the rest of Mantle’s life listening to a near-crippled alcoholic lament over and over about what he might have been able to accomplish. For an entire generation of fans and sportswriters who saw their own boyhood fantasies reflected in Mantle’s career and their worst nightmares fulfilled by his after-baseball life, Mantle’s decline became the dominant part of the story.

It’s time to dispel this myth . . . He was one of the most complete players ever to step on a big league field, a hitter with a terrific batting eye . . . spectacular power, blinding speed, and superb defensive ability. He could do things none of his contemporaries could do . . . He could switch-hit for high average and power, and he could bunt from either side of the plate, and no great power hitter in the game’s history was better at stealing a key base or tougher to catch in a double play . . . That his life is a cautionary tale on the dangers of success and excess can not be argued, but as a player he has a right to be remembered not for what he might have been but for what he was.

Of course Barra was and remains right. Even Mantle’s most unapologetically cynical observers buy that of course he’d have smashed Babe Ruth to smithereens, of course he’d have out-run Willie Mays in center field, of course he’d have out-stolen Ty Cobb first, of course he’d have left an impossible bar to clear, if only his lifelong-troublesome legs and a less young-death-present upbringing had left him the whole body and fully sound mind do it.

(For a contrast, hark back to Jim Bouton’s original lament in Ball Four: “Like everyone else on [the Yankees], I ached with Mantle when he had one of his numerous and extremely painful injuries. I often wondered, though, if he might have healed quicker if he’d been sleeping more and loosening up with the boys at the bar less. I guess we’ll never know.” Critics crucified Bouton over that, written in 1969-70. Whoops.)

If only. Enough.

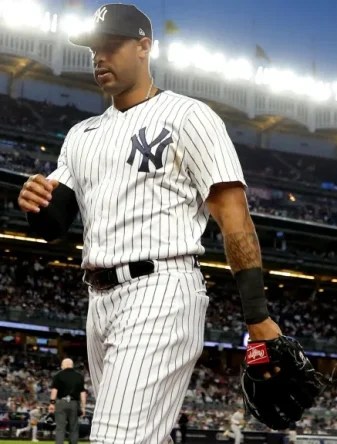

When Barra wrote, no player—not Hall of Famers Lou Gehrig, Yogi Berra, Babe Ruth, nobody—played more games as a Yankee than Mantle’s 2,401. Hall of Famer Derek Jeter got to play two more seasons and 346 more. Jeter’s the only Yankee to suit up in the fabled pinstripes for more games than Mantle did.

If you want to lament what couldawouldashouldamighta been for Mantle, you should keep it to his center field play. That’s where his notorious legs really cost him. Sure, he could run a fly ball down with the best (he saved Don Larsen’s World Series perfect game with just such a running stab), but he finished his career ten fielding runs below his league average in center field—and only once was good for ten or more above it. (In 1955.)

Mantle had an excellent throwing arm but his legs kept his range factors at his league’s average as long as he played center field. He had twenty outfield assists in 1954 . . . and ten or more only twice more his entire career, both in the 1950s. His legs also hurt him on the bases: he did finish with an .801 stolen base percentage, but playing in the time when the running game returned he never stole more than 21 bases in a single season.

But . . . he did take extra bases on followup hits 54 percent of the time he reached base in the first place. Willie Mays out-stole him (and led the entire show annually from 1956-58), yet Mays finished with a slightly lower lifetime stolen base percentage. (.767.) In center field? No contest. Mays was worth +176 fielding runs lifetime.

So who was really better at the plate? I’m going to repeat a table I posted as a footnote a few days ago, when I assessed where Mike Trout sits among Hall of Fame center fielders who played all or most of their careers in the post-World War II/post-integration/night-ball era. The table looks at those center fielders according to my Real Batting Average metric: total bases + walks + intentional walks + sacrifice flies + hit by pitches, divided by total plate appearances:

| Player | PA | TB | BB | IBB | SF | HBP | RBA |

| Mickey Mantle | 9907 | 4511 | 1733 | 148 | 47 | 13 | .651 |

| Willie Mays | 12496 | 6066 | 1464 | 214 | 91 | 44 | .631 |

| Ken Griffey, Jr. | 11304 | 5271 | 1312 | 246 | 102 | 81 | .620 |

| Duke Snider | 8237 | 3865 | 971 | 154 | 54** | 21 | .615 |

| Larry Doby | 6299 | 2621 | 871 | 60 | 39** | 38 | .576 |

| Andre Dawson | 10769 | 4787 | 589 | 143 | 118 | 111 | .534 |

| Kirby Puckett | 7831 | 3453 | 450 | 85 | 58 | 56 | .524 |

| Richie Ashburn | 9736 | 3196 | 1198 | 40 | 30** | 43 | .463 |

| AVG | .576 | ||||||

Mantle’s RBA is twenty points higher than Mays. (Trout, I repeat, is 21 points higher than Mantle at this writing, believe it or not.) You might notice that he took almost two hundred more walks than Mays despite playing several seasons fewer. They actually finished with the same average home runs per 162 games (36), but Mays was the far more difficult strikeout: 66 per 162 games, compared to Mantle’s 115.

So where would Mantle finish with an RBA twenty points higher than Mays. Look deeper. Mantle hit into far fewer double plays than Mays did. Even with his badly-compromised legs, which you might think would get him thrown out at first a little more often in such situations, Mantle hit into 138 fewer double plays than Mays did.

Here’s a couldashouldawouldamighta for you: Imagine how many fewer double plays Mantle might have hit into if he had healthy or at least less-frequently-injured legs. Today’s blowhard fans, writers, and talking heads love to yap about the guys who strike out 100+ times a year. Ask them whether they’d take Mays’s 66 against 11 GIDPs a year . . . or Mantle’s 115 against six.

Try this on for size. Mantle was seen so often as lacking compared to the Hall of Famer he succeeded in center field, Joe DiMaggio. Yet, and Barra himself noted this in the aforementioned book, Mantle averaged 83 more strikeouts than DiMaggio . . . but DiMaggio hit into seventeen more double plays even playing five fewer seasons. When last I looked a strikeout was a single out. (Unless, of course, you swing into a strike-‘im-out/throw-’em-out double play, and we don’t know how many of those were involved in Mantle strikeouts.)

Here’s another: In the same era, only three players have win probability added numbers above 100. In descending order, they are: Barry Bonds (127.7), Ted Williams (103.7), and Mays (102.4). Henry Aaron’s 99.2 is just behind Mays; Mantle’s 94.2 is right behind Aaron. Those are the only five players from the same era with WPAs 90 or higher. (Did I forget to mention Teddy Ballgame whacked into 197 double plays?)

If you still want to tell me that a guy with a 94.2 win probability added factor “didn’t live up to his potential,” go right ahead. But then I’m going to tell you that we don’t have to wonder what couldawouldaashouldamighta been if Mantle’s physical and mental health allowed.

They didn’t calculate wins above replacement-level player [WAR] when Barra wrote Clearing the Bases, alas. Mays (156.1) has Mantle (110.2) beaten by ten miles. Mantle was 36 when he retired. Mays from 36-40 was still worth an average 5.0 WAR a season, which is actually still All-Star caliber. It’s not Mantle’s fault Mays’s body allowed him a longer useful baseball shelf life. Any more than it was Mays’s fault he didn’t get to play on more than four pennant winners and one World Series champion.

I don’t know if the foregoing will put a lid on the couldawouldamightashoulda stuff around Mantle once and for all. But I can dream at least as deeply as all those fans and sportswriters did when Mantle was in pinstripes doing things nobody else save one in his time did, and doing it for teams that won twelve pennants and seven World Series rings while he did them.

For me, I haven’t cared about how great he couldawouldamightashoulda been since I first read Barra’s book. I still don’t. Pending the final outcome of Mike Trout’s career (Trout, too, has had injury issues enough the past three seasons, and he’s right behind Mantle as the number five center fielder ever to play, according to Baseball Reference), Mantle and Mays remain the two single greatest all-around position players who ever suited up.

It’s still heartbreaking to remember Mantle apologising for and owning what he wasn’t in life itself not long before his death. But he owes nobody any apology for what he was on a baseball field in spite of his compromised health. Barra remains right: “as a player he has a right to be remembered not for what he might have been but for what he was.”

———————————————————————————-

* My personal favourite story about Mickey Mantle and Casey Stengel: When Mantle first became a Yankee, the team was scheduled to play an exhibition with the Dodgers in Ebbets Field before the regular season began. Stengel took Mantle to the once-fabled Ebbets Field wall from right field to center field, bisected by a giant scoreboard and beveled to create an angle toward the field in its lower half.

Stengel wanted to show Mantle the tricky angles made by the scoreboard and the bevel. “Now, when I played here,” Stengel began. He was cut off by Mantle exploding into laughter, hollering, “You played here?!?” (Stengel did, as a contact-hitting, base-stealing outfielder with the Dodgers from 1912-1917, then with three other National League teams including the Giants from 1918-1925.)

“Boy never saw concrete,” the Ol’ Perfesser told a reporter who happened to overhear the exchange. “He thinks I was born sixty years old and started managin’ right away.”