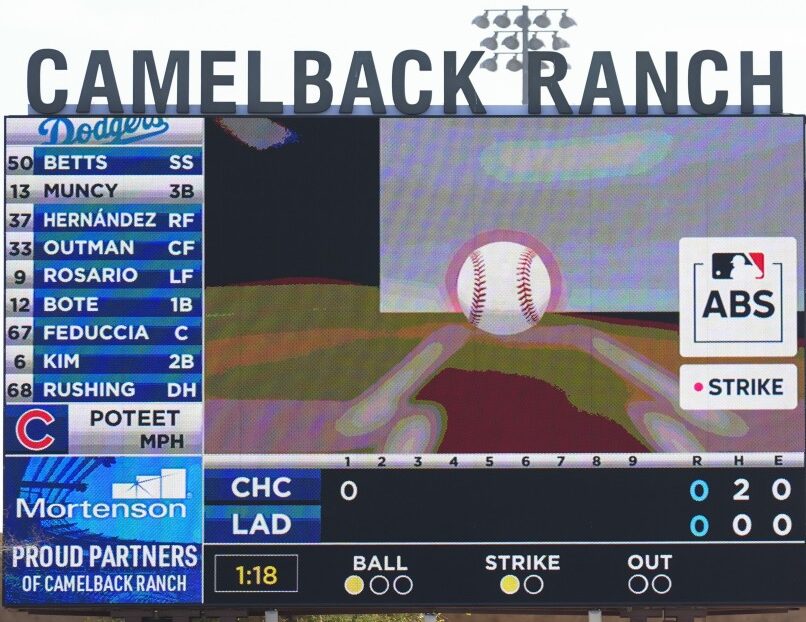

Kerkering’s mistake throw home sailing wide left of Phillies catcher J.T. Realmuto as Hyeseong Kim hits the plate with the Dodgers’ NLCS ticket punch. (ESPN broadcast capture.)

In Greek mythology, Orion is the mighty hunter who was felled by either the bow of the goddess of the hunt Artemis or by the sting of a giant scorpion. In National League division series Game Five, Orion was Kerkering, the Phillies relief pitcher stung in the bottom of the eleventh by the gravest mistake of any 21st century Phillie, ever.

If Kerkering wanted immediately to scream for help, you wouldn’t have blamed him. If the next place he really wanted to be was a Himalayan cave at altitude high enough to stop anyone from finding him, you wouldn’t have blamed him for that, either.

Baseball players and other professional athletes are human enough to make grave mistakes on the field. Many of them play for teams whose fans run the gamut from entitled to fatalistic to . . .

Well, put it this way. Again. Those playing in Phillies uniforms represent a city about which it’s said, often enough, that a typical wedding finishes with the clergyman pronouncing the happy couple husband and wife before telling the gathering, “You may now boo the bride.”

So let’s say a prayer, or three, or ten, for Kerkering. Let’s pray that, no matter how the rest of his baseball career goes, he has the heart and soul to stand up, count himself a man, acknowledge that he blew it bigtime enough, and stare the infamous Philadelphia boo birds down without giving in to the temptation to hunt them down for Thanksgiving dinner.

With the bases loaded and two outs Thursday evening, Kerkering served Dodgers center fielder Andy Pages a sinker that didn’t fall from the middle of the strike zone. Pages whacked a two-hop tapper back to the box. Kerkering sprang forward and knocked the ball down, then reached to retrieve it with his bare hand.

Phillies catcher J.T. Realmuto stood fully erect and pointed to first base, with Pages about halfway up the line and Dodgers pinch runner Hyeseong Kim hurtling down the third base line. In a single instant, Kerkering went for what he thought would be the quickest out, as opposed to what every soul in Dodger Stadium expected to be the sure, guaranteed-not-to-tarnish, twelfth-inning-securing out.

He threw home, where he had no shot at bagging Kim, instead of to first baseman Bryce Harper, where he still had a clean shot at bagging Pages. The throw went wide left of Realmuto at the moment Kim hit the plate with the Dodgers’ National League Championship Series ticket punched by his spikes.

Thus ended a game during which neither the Phillies nor the Dodgers flashed anything resembling their usually powerful offenses, while both teams fought a magnificent pitching duel. Whether the 2-1 final was the Phillies losing or the Dodgers winning, take your pick.

Kerkering didn’t duck, either, once he arose from his haunches in front of the mound while the Dodgers celebrated and then let a teammate urge him out of the dugout into the clubhouse for comfort. Then, facing reporters, Kerkering owned up without hesitation.

“I wouldn’t say the pressure got to me. I just thought it was a faster throw to J.T., a little quicker throw than trying to cross-body it to Bryce,” he said. “It was just a horse [manure] throw . . . This really [fornicating] sucks right now.”

Until Kerkering’s mishap, the Dodgers’ sole score was a bases-loades walk Mookie Betts wrung out of Phillies reliever Jhoan Duran in the bottom of the seventh. And the Phillies’s sole score came in the top of that inning, when Nick Castellanos sent Realmuto home with a double down the left field line.

Other than that, neither side had any real solutions to the other guys’ effective starting pitchers, Tyler Glasnow for the Dodgers and Cristopher Sanchez for the Phillies. These lineups, full of MVPs and big boppers and rippers and slashers, never landed the big bop or rip or slash.

Until Pages swung at Kerkering’s second service of the plate appearance, the story of the game figured far more to be the Dodgers’s Roki Sasaki, the starter who ran into shoulder trouble early in the season, returned to finish the season as a reliever, and now found himself the jewel of a Dodger bullpen about which “suspect” was the most polite adjective deployed.

Sasaki merely spent the set appearing in three games, allowing not one Phillie run, and keeping his defense gainfully employed. The record says he pitched 4.1 innings in the series. He pitched three of them Thursday, the eighth, ninth, and tenth. Whatever he threw at them, not one Phillie reached base. Two struck out; four flied, lined, or popped out; three grounded out. If the Dodgers could have won it in the tenth, Sasaki had a case as a division series MVP candidate.

The Phillies’s usual closer, Jhoan Duran, found himself deployed earlier than usual, relieving Sanchez in the seventh. After Betts’s RBI walk, Duran settled, ended the seventh, and pitched a shutout eighth. Matt Strahm succeeded him for a shutout ninth, and Jesús Luzardo—who was supposed to have been the Phillie starter if the set got to a fifth game—worked a shutout tenth.

Alex Vesia took over for the Dodgers in the top of the eleventh. He walked Harper, then wild-pitched him to second with two outs. Then he fought Harrison Bader—usually the Phillies center fielder but reduced to pinch hitting thanks to a bothersome groin injury—to a full count and a tenth pitch before he pulled Bader into a swinging strikeout.

Luzardo went back out for the eleventh. The tone of the game still suggested it wasn’t going to end too soon. Then Tommy Edman rapped a one-out single down the left field line, with Dodger manager Dave Roberts sending Kim out to run for him. Will Smith lined out deep enough to center field, but Max Muncy grounded a base hit past the left side of second base, pushing Kim to third.

Phillies manager Rob Thomson lifted Luzardo in favour of Kirkering, the 24-year-old righthander who’d become one of their more important bullpen bulls as the postseason arrived. He’d gone from untrusted to unimportant to invaluable in one year.

Now the Phillies needed him to push this game to a twelfth inning in which both teams were all but guaranteed to throw what little they had left at each other until one of them cracked. First, he had to tangle with Enrique Hernández. While Muncy helped himself to second on fielding indifference, Hernández worked out a six-pitch walk.

Up stepped Pages. Into the night went the Phillie season.

Realmuto was just one Phillies teammate trying to make sure Kerkering could shake it off and not do as Kyle Schwarber advised, let one bad moment define his career and life. (ESPN broadcast capture.)

Kerkering sank in front of the mound as the Dodgers poured out to celebrate around and behind. Nothing mattered to him or to the Phillies now. Not even the unlikely fact that the Phillies had kept Shohei Ohtani, the Dodgers’ best hitter and the best hitter in the game who isn’t named Aaron Judge this year, toothless, fangless, and clawless throughout the set, 1-for-18 with a single RBI hit and nine strikeouts.

The Dodgers weren’t sure what to think, either. “That,” Vesia said postgame, “was a badass baseball game.” Through ten and a half innings, yes. What to call the bottom of the eleventh would probably take time. Even “disaster” seemed like a disguise.

But Thomson and the rest of his players had no intention of throwing Kerkering under the proverbial bus. Realmuto made sure to be the first to embrace and try to comfort him. Castellanos, who’s endured his own share of trials and tribulations, sprinted in to get to Kerkering with brotherly comforts.

“I understand what he’s feeling,” said the Phillies right fielder. “I mean, not the exact emotions. But I can see that. I didn’t even have to think twice about it. That’s where I needed to run to.”

The same mind set overtook Schwarber, who’d done more than enough to push the Phillies toward Game Four after losing the first two in Philadelphia, especially his space launch of a home run in the fourth to tie the game and start the Phillies toward the 8-2 win. (He helped the piling-on with a second bomb, too.) “One play shouldn’t define somebody’s career,” said the Schwarbinator in the clubhouse. “I’ve had tons of failures in my life.”

Just how that team will be defined going forward is up in the air for now. Realmuto, Schwarber, and pitcher Ranger Suárez can become free agents come November. But the Phillies are expected to push to entice Schwarber to re-up, and Realmuto is still too valuable behind the plate for the team to let walk without trying to keep him, too, especially since the organisation is considered very lacking in catching depth.

“I’m thinking about losing a baseball game. That’s what it feels like right now,” said Realmuto after Game Four. “The last thing I’m thinking about is next year.”

Schwarber, too, preferred to stay in most of the moment. “This is a premier organization,” said the designated hitter who sent 56 home runs into orbit during the regular season. “And a lot of people should feel very lucky that you’re playing for a team that is trying to win every single year, and you have a fan base that cares and ownership that cares and coaches that care. You have everyone in the room that cares. We’re all about winning, and it’s a great thing. That’s why it hurts as much as any other year.”

These Phillies lost the 2022 World Series in six games, the 2023 NLCS in seven, a division series last year in four, and a division series this year in four. What’s up in the air right now just might turn to finding where and making changes enough. Especially since the average age of their regulars this year was 31. (The two youngest regulars, Brandon Marsh and Bryson Stott, are 27.)

Right now, they’re entitled to lie down and bleed. None more so than one young reliever who may not find comfort in knowing that he wasn’t the sole reason the Phillies fell short yet again. He may not find comfort yet in knowing that his teammates outscored the Dodgers by two runs across the entire division series but still couldn’t cash more than one scoring chance in in Game Four to make a difference.

“I feel for him,” Thomson told the postgame press conference about Kerkering, “because he’s putting it all on his shoulders. But we win as a team and we lose as a team.”

His sole comfort for now might be his teammates having his back. “Just keep your head up,” he said was their collective message to him. “It’s an honest mistake. It’s baseball. S— happens. Just keep your head up, you’ll be good for a long time to come. Stuff like it’s not my fault—had opportunities to score. Just keep your head up.”

The question is whether the more notorious side of Philadelphia fandom will try to knock his head off while he tries keeping it up. Maybe—as happened so notoriously to Mitch (Wild Thing) Williams after he surrendered a 1993 World Series-losing home run to Joe Carter—Kerkering’s refusal to hide and willingness to own up should help.

Or not, unfortunately. Even if Kerkering didn’t throw a World Series-losing pitch but committed only a division series-losing error.

If not, it’ll come to whether the worst sides of Philadelphia fandom compel the Phillies brain trusts to decide, however good his pitching future might be, that it’s not safe for him to see it in a Phillies uniform.

Maybe someone should find ways to ask those sides pre-emptively whether they would have had half the fortitude to own up to a grave on-the-job mistake made in front of 50,000+ fans in a ballpark, and a few million more watching on television, or streaming online, or listening to the radio.

As with too many others who hammered those I call Merkle’s Children—Fred Merkle himself, plus Williams, Ralph Branca, Bill Buckner, John McNamara, Donnie Moore, Don Denkinger, Tom Niedenfeuer, Gene Mauch, Johnny Pesky, Mickey Owen, Ernie Lombardi, Fred Snodgrass, maybe every St. Louis Brown ever—you might be lucky to find a very few who’d answer, “Yes.”