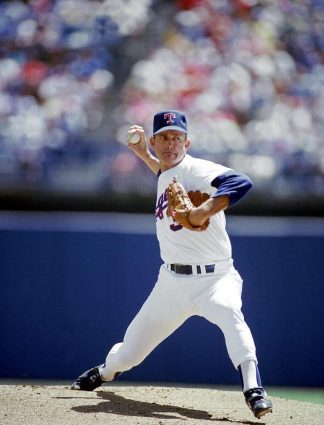

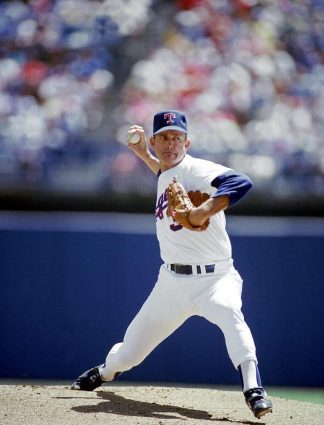

This is the way to remember Nolan Ryan—as a great pitcher, not the guy who got buried alive in a nasty brawl with the White Sox.

At the rate it turns up on social media discussions, and not merely on its anniversary, Hall of Fame pitcher Nolan Ryan is going to be remembered purely for the day he drilled Robin Ventura into charging the mound. As if nothing else he accomplished in a quarter-century plus pitching career mattered half as much as putting a temporarily brain-damaged third baseman in his “place.”

As if Ventura got the worst in a Ryan headlock that triggered a bench-clearing brawl between Ryan’s Rangers and Ventura’s White Sox in which Ryan got far worse than he inflicted upon Ventura. As if Ryan, in what proved his final season, was some sort of saint and Ventura some sort of bandit. As if there hadn’t been tension between the two teams for going on four full years.

It’s time to put the whole damn business to bed where it belongs. There were far more important things to think about to open this August. Things like Blake Snell’s no-hitter, Jack Flaherty’s Dodger debut, the sad end to yet another season from yet another injury to Hall of Famer-in-waiting Mike Trout. Things like the White Sox losing a twentieth straight game. Things like José Abreu hitting two bombs his first game back from his grandmother’s death and Freddie Freeman’s Guillain-Barre syndrome-afflicted little son home from the hospital.

But no. Who needs those when you can bring up the Ryan-Ventura brawl, a textbook exercise in celebrating false masculinity and baseball brain damage, on its anniversary, which is rendered meaningless anyway for how often it gets brought up all year long on one or another social media outlet?

Ryan was of the school of thought that taught the outer half of home plate was the pitcher’s exclusive property. You won’t find that anywhere in baseball’s written rules, of course. Generations of pitchers have been taught that; generations of hitters have been taught likewise. Well, now.

The Ryan-Ventura brawl was impregnated by a 1990 White Sox rookie named Craig Grebeck. He’d go on to make a useful career as a defense-first utility infielder. But in spring training 1990 he shocked a lot of people—probably including Ryan, probably including his own team—when he homered against the Rangers on a first pitch. He pumped his fists rounding the bases.

Come the regular season, Ryan faced Grebeck and surrendered one of (read carefully) the nineteen major league home runs Grebeck would ever hit in a twelve-season career. Again, Grebeck pumped his fists rounding the bases. Back on the bench, Ryan asked pitching coach Tom House about him.

Told that it was Grebeck, a not so tall player who looked then like a boy entering middle school, Ryan is said to have told then-Rangers pitching coach Tom House, according to Ryan biographer Rob Goldman, “Well, I’m gonna put some age on the little squirt. He’s swinging like he isn’t afraid of me.” The next time Grebeck faced him, Ryan hit him in the back with a pitch. “Grebeck was 0-for the rest of the year off him,” House remembered.

Fat lot of good that did The Express: Grebeck actually finished his career with a .273/.429/.545 slash line and a .974 OPS against the Hall of Famer. It wasn’t exactly a powerful one (three singles, two walks, three strikeouts, but four runs batted in, somehow), but Ryan didn’t exactly age Grebeck with the first of only two drills he’d hand Grebeck lifetime, either.

What it did, though, was begin some very tense times between Ryan’s Rangers and Grebeck’s White Sox. The White Sox’s batting coach, Walter Hriniak, was teaching his charges to cover that outer half of the plate. House insisted that was a root but Ventura himself said otherwise. “At the time in baseball the (strike) zone was low and away, and that was where pitchers were getting you out,”he said. “We weren’t the only team doing it. It was the kind of pitch that was getting called, so you just had to be able to go out and get it.”

What followed:

17 August 1990: Ryan hit Grebeck with one out in the third, Grebeck’s first plate appearance of the game. Two innings later, White Sox starter Greg Hibbard hit Rangers third baseman Steve Buechele with two outs. (The game went to extras and the Rangers won, 1-0, when Ruben Sierra walked it off with a line drive RBI single in the thirteenth.)

6 September 1991: Ryan hit Ventura in the back on 1-2, also in Arlington, three innings and a ground out after Ventura doubled Hall of Famer Tim Raines home with nobody out in the top of the first and scored on Lance Johnson’s subsequent two-out single. It started a rough day for Ryan, who surrendered two more runs (both on third-inning sacrifice flies) en route an 11-6 White Sox win.

2 August 1993: This was two days before Ryan and Ventura’s rumble in the jungle: Rangers pitcher Roger Pavlik hit White Sox catcher Ron Karkovice with one out in the third. (Ventura posted a first-inning RBI single to open the scoring; Rangers left fielder Juan Gonzalez answered with a two-run homer in the bottom of the first. Subsequently, White Sox relievers Bobby Thigpen and Jason Bere each hit Rangers third baseman Dean Palmer, while Rangers shortstop Mario Díaz also took one from Thigpen.

Ventura and assorted White Sox teammates of the time insisted Ryan was throwing at hitters and often hitting them on a routine bases. Two days later, Ryan and Ventura went at it. Among the pleasured by Ventura charging Ryan was Sox pitcher Black Jack McDowell: “Ryan had been throwing at batters forever, and no one ever had the guts to do anything about it. Someone had to do it. He pulled that stuff wherever he goes.”

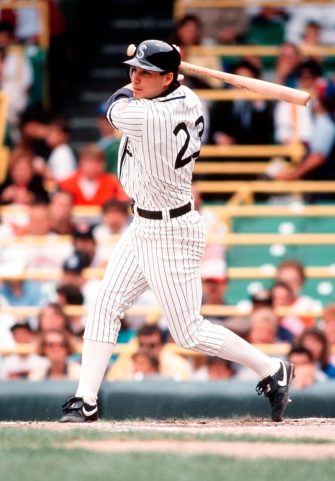

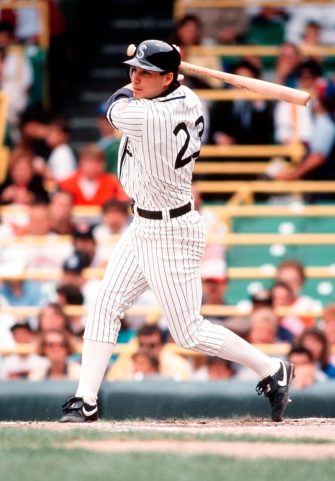

And this is the way to remember Robin Ventura—a great third baseman, not the guy who charged the mound indignantly when Ryan hit him with a 1993 pitch after a few seasons of White Sox-Ranger knockdown-and-plunk tensions.

“We had a lot of going back and forth that season,” says Ventura. “Guys were getting hit regularly, and it was just one of those things where something was going to eventually happen.” It probably involved other Rangers and White Sox pitchers, too.

Ryan was as notorious for his career-long wildness (he led his league six times and the entire Show three times in wild pitches, and averaged twelve per 162 games lifetime) as for his seven no-hitters, his 5,714 lifetime strikeouts, and his 2,795 walks. (They’re also number one on the Show hit parade.) He may have gotten away with throwing at hitters, but he was actually pretty stingy when it came to actually hitting them.

He retired averaging seven hit batsmen per 162 games. Seven. If he’d actually hit seven men a year for his entire career, it would give him 31 more drilled than he actually compiled (158). He actually had eleven seasons in which he hit five batters or fewer; hitting Ventura on that fine 4 August 1993 was the only hit batsman Ryan had in thirteen 1993 starts before he finally called it a career.

That doesn’t exactly sound like one of the most merciless drillers the game’s ever seen. Ryan only ever led his league in hit batsmen once (1982, when he was an Astro), and that’s one more than Hall of Famer Bob Gibson—too often the unjustified first name in, ahem, manly intimidation—ever did. Believe it, or not. Ryan is number sixteen at this writing on the all-time plunk parade. Gibson, you might care to note, is tied for 89th on the parade with (wait for it) 102. And he averaged (wait for it again!) . . . six per season.

“If you look at the replays, the ball wasn’t really that far inside,” House told Goldman.

It was just barely off the plate and it went off Ventura’s back. Robin was starting toward first base when he abruptly turns and charges the mound instead. And the closer he got to Nolan, the bigger he looked. If you watch it in stop action, you can see Ryan’s eyes were like a deer’s in a headlight. So everybody was surprised by what Nolan did next: Bam! Bam! Bam! Three punches right on Ventura’s noggin!

Actually it was about six. Now for the part everyone still gaping in awe over Ryan’s manly deliverance of a lesson to Ventura forgets: Both teams swarmed out of their dugouts, but the White Sox got to Ryan so swiftly that they drove him to the bottom of a pileup from which the White Sox’s Bo Jackson had to extricate Ryan before some serious damage was done to the veteran righthander.

“All I remember,” Ryan eventually told Goldman, “is that I couldn’t breathe. I thought I was going to black out and die, when all of a sudden I see two big arms tossing bodies off of me. It was Bo Jackson. He had come to my rescue, and I’m awful glad he did, because I was about to pass out. I called him that night and thanked him.” (The two were friendly rivals since then-Royal Jackson hit Ryan for a 1989 spring homer and his teammates hailed Ryan the next day—from the spot where Jackson’s bomb landed, as Ryan went through an exercise routine on the field.)

Ryan otherwise actually got the worst of it when all was said and done. Jackson extracted a man “visibly winded,” Goldman wrote. Ryan wasn’t the only one thankful for Jackson. “When Nolan didn’t come out of the pile, I got concerned,” said his wife, Ruth. “With his bad back, sore ribs, and other ailments, he could easily have suffered a career-ending injury.”

Somehow, Ryan remained in the game. Ventura was ejected for charging the mound. Of all people, his pinch runner was . . . Craig Grabeck. Ryan picked Grabeck off first before he threw a single pitch to the next batter, Steve Sax, who grounded out to end the inning.

The Rangers went on to win, 5-2. Ryan insists to this day that if Ventura had stopped shy of the mound rather than finish the pursuit and grab his jersey, “I wouldn’t have attacked him.” But he also felt embarrassed by the brawl. So much so that, Goldman recorded, when the Ryan family returned home from a postgame family dinner, Ryan declined when one of his sons—who’d videotaped the scrum—asked Dad if he wanted to see it again.

Ryan’s no, Goldman noted, was “firm.”

Said the Dallas Morning News headline the day after: Fight Gives Game a Big Black Eye.

Now, if rehashing that brawl isn’t to Nolan Ryan’s taste, it ought to be lacking likewise for the idiots who insist on reliving and re-viewing it on social media—and not just on its anniversary. I could be wrong, but it seems that social media outlets can’t last two weeks, and possibly less, without at least one jackass posting the video of the scrum.

Pitching to the inside part of the strike zone is part of the art, even if there’s no written rule saying the outer half of the plate is the pitcher’s exclusive property. You can delve as deep as you want and discover there were plenty of pitchers who lived so firmly on the inside that they, too, earned unfair reputations as headhunters.

Not everyone is as shameless as shameless as fellow Hall of Famer Early Wynn insisting he’d knock his grandmother down if she “dug in” against him. Well, guess what. Grandma’s Little Headhunter hit only 64 batters in a 23-season career and averaged only three per 162 games lifetime. He even had eleven seasons where he hit three batters or less.

Once upon a time, Bob Gibson signed an autograph for a fan who told him, in the earshot of baseball writer Joe Posnanski, “Oh, do I remember the way you pitched. I remember all those batters you hit. They were scared of you. The pitchers today, they couldn’t hold a candle to you.”

Gibson did want the edge every time he took the mound. He did look as ferocious as his reputation on the mound, though that may have been as much a byproduct of his nearsightedness as anything else he brought to the mound, including an innate and justifiable sense that a black pitcher in his time and place needed the edge just that much more. He did pitch inside as often as he thought he had to to keep batters off balance.

But when that fan departed with his autograph, Gibson turned to Posnanski and probably sounded wounded when he asked, “Is that all I did? Hit batters? Is that really all they remember?” (If it is, they didn’t see him pitch his way to the Hall of Fame.)

A few years ago, in another online forum, I was addressed directly by a fan who objected to my recording that, among other things, Gibson didn’t hit as many home run hitters after their bombs as people think they remember: He wasn’t just ‘brushing back’ batters—especially those who had hit a donga off him the time before. He was damn well trying to hit them.

Well, I was crazy enough to look it up. Here’s what I wrote then:

Thirty-six times in 528 major league games Bob Gibson surrendered at least one home run and hit at least one batter in the same game. He only ever hit one such bombardier the next time the man batted in the game; he hit three such bombardiers not the next time up but in later plate appearances in games in which they homered first; and he surrendered home runs after hitting batters with pitches in fourteen lifetime games.

For the record, the one batter Gibson hit in the next plate appearance following the homer was Hall of Famer Duke Snider. The three bombers he’d hit later in those games but not in their most immediate following plate appearances: Hall of Famer Willie Stargell plus longtime outfielders Willie Crawford and Ron Fairly.

Is that all I did? Hit batters? Is that really all they remember?

Is that all I did? Sock Robin Ventura six times in a headlock before I got buried alive in the bottom of a pileup in my last year in the bigs and I needed Bo Jackson to save my sorry behind?

Ryan is a Hall of Fame pitcher. Ventura had an excellent career that shakes him out as the number 22 third baseman ever to play the game. They both deserve far better than to be remembered first for a hit-by-pitch and brawl that lowered both men’s dignity a few levels. The fans who “celebrate” the brawl every week or two, never mind on its anniversary? They deserve to be condemned.