Arizona pitcher Merrill Kelly leaving NLCS Game Two in the sixth inning and hearing it from the Citizens Bank Park crowd whose sound he underestimated. He ended up bearing the least of the Phillies’ destruction on the night.

Maybe nobody gave Diamondbacks pitcher Merrill Kelly the memo. Maybe he missed the sign completely. Wherever Kelly happened to be, if and when he was warned not to poke the Philadelphia bear and his native habitat, he learned the hard way Tuesday night and the Diamondbacks whole were dragged into class.

Maybe the Braves sent him a message he never saw. You remember the Braves. The guys trolling Bryce Harper after their second division series game, when Harper got doubled up on a very close play following an impossible center field catch to end the game. They learned the hard way, too. They’re also on early winter vacation.

Before this National League Championship Series even began, Kelly was asked whether the heavy metal-loud Citizens Bank Park crowd might have a hand in the field proceedings. He practically shrugged it off, though in absolute fairness he wasn’t exactly trying to be mean or nasty.

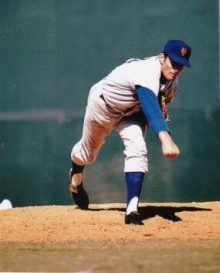

“I haven’t obviously heard this place on the field, but I would be very surprised if it trumped that Venezuela game down in Miami [in the World Baseball Classic],” said Kelly, a righthander whose countenance bears a resemblance to comedian Chris Elliott and who’s considered a mild-mannered young man otherwise. “When Trea [Turner] hit that grand slam, I don’t think I’ve ever experienced—at least baseball-wise, I don’t think I’ve ever experienced an atmosphere like that so I hope that this isn’t louder than that.”

That grand slam jolted Team USA into the semifinal round. By the same Trea Turner who’d start Kelly’s Tuesday night with a jolt, hitting a one-out, one-strike pitch into the left center field seats in the bottom of the first.

Kelly may not have been trying to be snarky, but The Bank let him have it early and often, first when he was introduced pre-game time and then when he took the mound for the bottom of the Game Two first. Loud, clear, and unmistakeable.

The only things Kelly faced louder and more clear than that were Turner’s score-starting blast, the one-ball, two-out laser Kyle Schwarber sent off Kelly’s best pitch, a changeup, into the right field seats in the third, and the 2-1 skyrocket Schwarber sent into the right center field seats leading off the bottom of the sixth.

“He’s really effective because he has a plus-plus changeup,” Schwarber said postgame. “He threw it 2-0 and kinda gave me the window. That’s what it looks like coming out of there. I think that was the first strike [on a] changeup I saw. [The home run pitch] was a little bit more down and away. But, I mean, it came out of the same height. So those are things that you look for.”

“They’re good big-league hitters,” Kelly said of the Phlogging Phillies postgame. “That’s what good big-league hitters do. They don’t miss mistakes.” Neither did The Bank’s crowd, serenading him with “Mer-rill! Mer-rill” chants at any available opportunity. But Kelly actually pitched decently despite the bombs. He only surrendered three hits, but walking three didn’t help despite his six strikeouts.

He’d also prove to have been handled mercifully compared to what the Phillies did to the Diamondbacks bullpen in a 10-0 Game Two blowout.

Once they pushed Kelly out of the game, with two out in the sixth and Turner aboard with a walk, they slapped reliever Joe (Be Fruitful and) Mantiply with a base hit (Bryson Stott), a two-run double (J.T. Realmuto), and another RBI double (Brandon Marsh). Just like that, the Phillies had a four-run sixth with six on the board and counting.

Then, Mantiply walked the Schwarbinator to open the Philadelphia seventh. Diamondbacks manager Torey Lovullo reached for Ryne Nelson. One out later, Harper singled Schwarber to third, Alec Bohm doubled them home with a drive that hit the track, Stott hit a floater that hit the infield grass between Nelson plus Diamondbacks third baseman Evan Longoria and catcher Gabriel Moreno, Realmuto singled Bohm home and Stott to third, and Nick Castellanos sent Stott home with a sacrifice fly.

This time they didn’t need Harper to provide the major dramatics. He’d done enough of that in Game One, hitting a first-inning, first-pitch-to-him, first-NLCS-swing, first-time-ever-on-his-own-birthday nuke one out after Schwarber hit his own first-pitch bomb. That game turned into a 5-3 Phillies win. On Tuesday night, they turned the Diamondbacks into rattlesnake stew.

They made life just as simple for Game Two starter Aaron Nola as for Game One starter Zack Wheeler. Wheeler gave the Phillies six innings of two-run, three-hit, eight-strikeout ball; Nola gave them six innings of three-hit, seven-strikeout, shutout ball. It was as if the Philadelphia Orchestra offered successive evenings of the Brahms Violin Concerto in D Major—featuring Isaac Stern one night and Itzhak Perlman the next.

“It’s a little more hostile and a little more engaging,” said Turner of the Bank crowd after the Phillies banked Game One. “I think [Kelly] can maybe tell you after tonight what it’s like, but I wouldn’t put anything past our fans. Our fans have been unbelievable. They’ve been great. I don’t know what decibels mean, but I guess we did something cool for AC/DC concert level decibels the other night . . . I would just wait and see and we’ll see what he says after [Game Two]”

“They’re up all game on their feet from pitch number one till the end,” said Nola postgame. “I feel like you don’t really see that too much around the league. That just shows you how passionate and into the game they are. They know what’s going on, and that helps us a lot.”

That was not necessarily what Lovullo wanted to hear before or after the Game Two massacre ended. “Everybody’s talking about coming into this environment,” he said, audibly frustrated, “and I don’t care.”

We’ve got to play better baseball. Start with the manager, and then trickle all the way down through the entire team. We’ve got to play Diamondback baseball . . . Diamondback baseball is grinding out at bats . . . driving up pitch counts, catching pop ups . . . win[ning] a baseball game by just being a really smart, stubborn baseball team in all areas.

That assumes the Phillies will just roll over and let them play it. The wild-card Diamondbacks who steamrolled two division winners in the earlier rounds to get here in the first place looked like anything except an unlikely juggernaut after getting manhandled in Philadelphia. They shouldn’t take the Phillies for granted once the set moves to Chase Field, either.

The Phillies might have been a one-game-over-.500 road team on the regular season, but they beat the Diamondbacks in Chase Field three out of four—a couple of weeks after the Snakes beat them two out of three in The Bank. Until this NLCS it was a little over three months since the two teams tangled. It certainly didn’t phaze the Phillies.

“I still think we’re real confident,” said Kelly. “I think there was a lot to be said about us after the All-Star break about how bad of a slump that we went into. I’ve seen in this clubhouse, I’ve seen from these guys that we haven’t gotten rattled all year. And I don’t want us to hang our heads and pout about it this time.”

But let’s say the Diamondbacks iron up and find ways to neutralise the Phillies’ offensive bludgeons and pitching scythes which, admittedly, might require a kidnapping or three. Let’s say they win all three games at Chase. They might become the only team to be at a disadvantage with a 3-2 series lead.

Because guess where the set would return then. And, unless my prowling has missed something this morning, Kelly didn’t have one word to say about that crowd after Game Two came to its merciful end. It must have been more than loud enough for him.