If you’ll pardon the expression, Braun cheated himself out of a Hall of Fame case.

A few weeks ago, I had a look at the holdovers on the current Baseball Writers Association of America Hall of Fame ballot. Included in my analysis of their cases was a promise, which some might deem a threat, to look at the newcomers in short order.

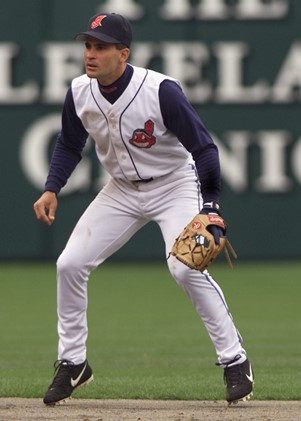

Well, the order was short enough. In the interim, the Contemporary Baseball Era Committee elected Jeff Kent to the Hall. So It’s time. But I’m going to tell you going in that I have a sneaking suspicion that Kent may stand alone among players at the Cooperstown podium next summer.

Which would probably drive to the nearest drink well those writers still standing who saw Kent in his prime. The ones who remember his feuding with a certain Giants teammate. The ones who knew concurrently that, without that teammate in the lineup ahead of him, Kent’s only passage to the Hall of Fame might be as a paying customer.

I’m not going to say, “Be afraid. Be very afraid.” But, and we’ll take these ballot rookies alphabetically . . .

Ryan Braun—Like Álex Rodríguez, Braun got himself caught as a customer of actual or alleged performance-enhancing substances from Biogenesis. Unlike A-Rod, that didn’t provoke Braun to litigiousness. His litigiousness happened earlier, when he tried suing his way out of a suspension when testing caught him using synthetic testosterone. He even accused a sample collector of anti-Semitism.

After serving his Biogenesis suspension, Braun went out of his way to self-rehabilitate. He apologised publicly to the collector he smeared; he revived his charitable activities. But he was also never again the player he was before his PED issues, thanks largely to injuries.

In peak and career value terms, his performance papers fall too far short of Hall-worthiness. In trying to go scorched-earth when caught red-handed (and probably red-faced), placing his entire pre-test/pre-suspension career into question (fairly or unfairly), Braun cheated himself out of a Hall case. No.

Shin-soo Choo—The second Korean position player to make it to the U.S. major leagues (Hee Seop Choi preceded him), Choo was as talented as the day was long and just about as unfortunate. Injury bugs got to him too often. At his best and healthiest, he was as solid a tablesetter as a lineup could have. But it’s not enough to strike a plaque in Cooperstown. No.

Edwin Encarnación—As a Blue Jay in the middle of his fifteen-year career, he was one of the American League’s most feared sluggers. He was also a better baserunner than you might remember. His defensive liabilities probably did the most to keep his peak and career values below the Hall of Fame averages.

But he and Toronto will always have that monstrous three-run homer to send the Jays to an American League division series after Buck Showalter’s brain fart meant Encarnación wouldn’t have to get through the 2016 AL’s best reliever, Zach Britton. No.

Gio Gonzalez—Likeable. Durable. Dependable. And, according to Baseball Reference, the number 309 starting pitcher of all time. One fielding-independent championship isn’t enough to get you to the Hall after a thirteen-year career. Twice leading your league in walks won’t, either. But you kind of had to love this guy.

In the pre-universal DH era, Gonzalez had an all-time freak stat: he struck out more pitchers batting against him than any other pitcher in four decades preceding him. Not a Hall stat, but certainly something to warm the hearts of those who know baseball really is a funny game. No.

Alex Gordon—It would be easy to dismiss him because of his modest batting statistics, but Gordon was one whale of a defensive left fielder. He has eight Gold Gloves and two Platinums, and he didn’t get them as participation trophies, either. He is, in fact, the number three left fielder ever for run prevention.

The only guys ahead of him there? Some dude named Bonds, and some Hall of Famer named Yastrzemski. That’s bloody well elite company he’s keeping there.

I don’t know if that alone will get Gordon into the Hall in due course. But I say “in due course” because I think his case deserves deeper looks and I suspect he’ll last on the ballot for another couple of years at least. Not now.

Cole Hamels—He looked like a Hall of Famer once upon a time. Especially when he helped lead the 2008 Phillies to a World Series triumph with a 1.80 postseason ERA that year, not to mention bagging the Most Valuable Player awards in the National League Championship Series and the World Series.

Talent to burn and perfectionism likewise, seemed to be the cumulative assessment, whether in Philadelphia, Texas, or Chicago. He also dealt with enough injury issues to make it difficult to impossible to build the Hall of Fame case he looked to be beginning in the glory days with the Phillies. But I suspect he might linger on the ballot another year, at least. No.

Matt Kemp—He, too, looked like a Hall of Fame talent when he arrived. The bad news was a) Kemp’s dynamic style was offset by his frequent inabilities to re-adjust when pitchers caught onto his fastball dependency at the plate; and, b) he was a defensive liability as often as not.

He hit with staggering power when he was right, especially his career year 2011. But when measured against the rest of his career overall, that turned out to be kind of a fluke season. Kemp’s real problem might have been being a designated hitter type who played in the wrong league in the pre-universal DH era. No.

Gallows pole: Kendrick’s power hitting helped the 2019 Nationals go all the way to the Promised Land.

Howie Kendrick—Eminently likeable, especially as his career neared its finish and he shone for the 2019 Nationals all the way through the postseason. Especially hitting a pair of ultimately game-winning home runs that paid the bill for every steak he might ever want to have in Washington for the rest of his life. (He also won that year’s NLCS MVP.)

Forgotten amidst those postseason heroics: Kendrick was a very solid second baseman, not quite an intergalactic presense there but in the plus column for run prevention. It won’t be enough to help him into Cooperstown, but when he was right he was a fine player and a terrific clubhouse element. No.

Nick Markakis—He’s one classic example of a terrific baseball player who was as solid as they came without being spectacular. (2,388 hits; 57 total zone runs as a right fielder.) Even as something of an on-base machine and a definite asset in right field, Markakis was the guy you couldn’t bear to replace, even if the rest of the world didn’t necessarily drop what it was doing when he checked in at the plate or ran down a right field fly. Not quite.

Daniel Murphy—A threshing machine at the plate for the pre-World Series 2015 postseason Mets, with those six consecutive games hitting a home run and breaking Hall of Famer Mike Piazza’s team record for total homers in a single postseason. Unfortunately, his Series fielding mishaps negated that hitting prowess on the way to the Mets’ Series loss to the Royals.

Murphy’s 2016 redemption (leading the NL in slugging and OPS) proved a one-off. His career overall was too far short of the Hall of Fame, but that pre-World Series postseason power display in 2015 keeps him a Met hero. No.

Hunter Pence—He got to play for two out of the three San Francisco Series winners in the 2010s. He was charmingly quirky, enough to earn a temporary trend of “ahhh, ya mother rides a vacuum cleaner” banners around the league. (Hunter Pence eats pizza with a fork! Hunter Pence says “Sorry” when he catches a fly! were typical.)

Well, Pence was a good, solid player when he wasn’t injured. That’s important and it counts, and if it’s married to a guy who’s delightfully flaky that’s a big plus. That might even keep him on an extra Hall ballot. Might. Not quite.

Rick Porcello—His 2016 American League Cy Young Award was an outlying season for him—especially since future Hall of Famer Justin Verlander should have won it. Porcello opened the next season with a 1.40 ERA and 1.74 FIP in his first four games. That season ended with him showing a 4.65 ERA/4.60 FIP.

That was Porcello. Periodic short bursts of greatness, modest longer terms. He was smart on the mound and relied on his defenses. But that’s not always going to make a Hall of Famer, either. No.

First published at Sports Central.