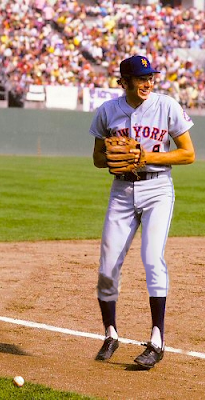

Just keeping this issue in the forefront is the best thing . . . Eventually, somebody who really has the power may say hey, I didn’t realise this was happening, let’s do something about it . . . Hopefully something can happen.”—George (The Stork) Theodore, a 1973 pennant-winning Met, shown here in 2016. (University of Utah photo.)

His major league playing career lasted 105 games, thanks largely to a 1973 outfield collision that resulted in a serious hip injury. But George (The Stork) Theodore remains a favourite among longtime Met fans and the organisation itself, invited to both the farewell of Shea Stadium and the opening of Citi Field, and invited to commemorations of the 1973 Mets’ pennant winner.

That was then: The 6’4″ Theodore endeared himself to fans with hustle when he got playing time, plus signing autographs amiably and talking to the sporting press with far more than mere boilerplate.

This is now: The Stork is a retired elementary school counselor, with a bachelor’s degree in psychology and master’s degree in social work, who’s been honoured for that work more than once, including an Educator of the Year award from the South Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce plus an Excel Teacher of the Year award.

“I was going to do that a few years. I was actually trained in medical social work,” said the 76-year-old former outfielder/first baseman, by phone from his Utah home, this week. “Then I found out that it was really my calling, and I enjoyed it, working with the young children in elementary school, and ended up with a career of 38 years there in the public schools.” About his awards as an educator, “I was honored at that, and humbled, because I didn’t feel I was any better than a lot of my compatriots.”

Drafted by the Mets in 1969, Theodore was a member of the ’73 pennant winner who had two World Series plate appearances, which he still calls “not bad” for a man who says he was on the Mets’ postseason roster mostly as a designated team cheerleader. But the Stork wishes only that the game he loved would favour himself and over five hundred more remaining players with short major league careers who played prior to 1980—and continue going without major league pensions.

He’s been interviewed often in the years since his playing career ended, but the pension issue isn’t always raised at those times. “It’s in a minor way,” he said of that subject, “but the interviews are basically about the ’73 team, though we try to sneak in something about the pension issue there.”

The issue, of course, is that when baseball’s owners and the Major League Baseball Players Association re-aligned the game’s player pension plan in 1980, they changed the vesting times to 43 days’ major league service time to qualify for full pensions and a single day’s service time to qualify for health benefits—but excluded such players as Theodore whose pre-1980 careers fell short of the former four-year vesting requirement.

Ask whether he could isolate whom among that year’s player representatives voted to exclude himself and his fellows—from each team’s player rep to then-league reps Steve Rogers (Expos pitcher, for the National League) and the late Sal Bando (Brewers third baseman, for the American League)—and Theodore isn’t entirely sure.

“I know they were kind of in a hurry to get [pension realignment] done to avoid a strike,” he said. “And I know that [original Players Association executive director] Marvin Miller—who was really the backbone of our union, getting all the wonderful things—was really disappointed that, as he looked back, that he didn’t pull in those people before and include them in that 1980 bargaining.”

The sole redress Theodore and the others have received since has been a stipend negotiated by the late Players Association executive director Michael Weiner with then-commissioner Bud Selig—$625 per 43-day service period, up to $10,000 a year before taxes. That amount was hiked fifteen percent as part of the 2021-22 owners’ lockout settlement. But the recipients still can’t pass those monies on to their families upon their deaths.

Had Weiner not died of brain cancer in 2013, would he have been able to go forward from the 2011 stipend deal to get something more? “That’s a good question,” Theodore answered. “The whole system is not one of legality, but one of ethics. Baseball didn’t turn out to be what it is now just on it’s own. It’s been a slow, steady, building block process. And every player who played was a part of that.”

The Players Association formed originally to address pension issues in 1954. Its annual revenues now are believed to be $56.8 million. MLB’s annual revenues reached a reported $10.5 billion in 2022. Both the owners and the players kick into the players’ pension fund.

If those numbers are accurate, they add up to $10,556,800,000 per year. The union and the owners could agree to grant the remaining 500+ frozen-out, pre-1980 short-career players full pension status—based on their 43-day major league service periods—without going broke by a far longer shot than anything Shohei Ohtani can hit over the fence.

“I was just happy to be playing baseball and excited to get any opportunities,” Theodore said of his career. “I was one of the last people drafted.” [In 1969, round 31; one of the very few drafted out of the University of Utah.] “And so I knew my career was always in jeopardy. I knew many of my friends who signed at the same time, they’d have a bad week or two and they were gone.”

Because of that, he said, he wasn’t involved directly in Players Association actions, and credits A Bitter Cup of Coffee author Douglas Gladstone for helping to make him and numerous others of his short-term peers aware of the pension shortcoming.

Several pre-1980 short-termers have said they believe they were frozen out of the realignment because they were seen mostly as September callups. But most of the surviving 500+ either made teams out of spring training at least once or saw major league action in months prior to any September. Theodore himself made the Mets out of spring training in 1973.

The Stork was considered a strong defender with a good throwing arm and league-average range. “I was a fast runner, too,” he said. But the lack of game action didn’t bode well for his improvement as a major league hitter despite having recording solid batting marks in the minors. He had a splendid .817 OPS to show for his minor league seasons and posted a .972 OPS between A level and AA ball in 1971.

“I needed to play in order to be like that,” Theodore said. “Like many young players, playing once or twice a week, you don’t get your reflexes that you need.”

Deployed mostly as a left fielder in the majors, Theodore swears his better position was first base, where he played in eighteen major league games including twelve starts. “But we had John Milner there,” he said, “and Ed Kranepool, too. First base was really where I think I was the most effective because of my size and range. I could prevent bad throws just by stretching out.”

Still, Theodore became a fan favourite. “I always appreciated that,” he said. “I just know that I tried to give my best any time I played. Whether it would end up that way or not. And I responded to the fans, too. I enjoyed meeting fans and giving autographs. It was all new to me and I enjoyed every minute of it.”

His nickname didn’t hurt, either. Minor league teammate Jim Gosger—once with the Red Sox; an original Seattle Pilot;, and, very briefly, a 1969 Met when he completed an earlier trade (he didn’t make their postseason roster), before moving to two more teams and returning for brief spells with the ’73-’74 Mets—hung it on him. Theodore denies the longtime story that Gosger came up with the nickname when seeing the tall man holding a teammate’s baby.

“But he did call me the Stork, somehow” he said, chuckling. “I’m not sure why he decided on that nickname, but it stuck, and it endeared me to a lot of people.”

Theodore was carried off the field on a stretcher after a hip-dislocating collision with center fielder Don Hahn on 7 July 1973. Surrounding are (left to right) manager Yogi Berra (8), right fielder Rusty Staub (4), relief pitcher Tug McGraw (45), and second baseman Felix Millan (16). Braves center fielder Dusty Baker (12) looked on in concern.

But whatever further progress the Stork might have made ran into a thunderous obstruction on 7 July 1973. Atlanta’s Ralph Garr whacked a seventh-inning drive toward which Theodore and his close friend, Mets center fielder Don Hahn, converged in left center . . . and collided violently. Theodore suffered a dislocated hip while Garr ran out what proved an inside-the-park two-run homer, and missed most of the rest of the season.

Call it a classic Mets example of no good deed going unpunished. An inning earlier, Theodore led off with a walk, took second on a sacrifice bunt, and scored the game-tying run when Hahn doubled deep to left. The collision and Garr’s inside-the-parker in the seventh put the Braves up 5-3 (they’d scored on an RBI single just before Garr batted); the Braves eventually won, 9-8, in a game that changed leads twice more before it finished.

Theodore said he might have matured into a solid major leaguer had it not been for that injury, but he remains grateful that the Mets put him on their 1973 postseason roster. The ’73 Mets were an injury-riddled team until key regulars returned for the September drive that ended—under relief pitcher Tug McGraw’s rallying cry “You gotta believe!”—with them winning the National League East and then the National League Championship Series from the Reds.

The Stork, tall and happy as a Met.

In the World Series, which the Athletics won in seven games, Theodore pinch-hit for Mets pitcher Ray Sadecki in Game Two in Oakland and grounded out to shortstop. In Game Four in New York, with the Mets up 6-1 (it proved the final score), Theodore was sent out to play left field in Cleon Jones’s stead for the top of the eighth, but he popped out to third base to end the bottom of the inning. Those were his only appearances that postseason.

“They didn’t have to do that,” he said of being on the postseason roster. “I hadn’t played for three months and I was more or less a cheerleader and emotional support for the team, until the World Series. Then all of a sudden I’m called to pinch hit and went into the outfield in another game.

“It’s funny how fate works,” the Stork continued. “Not playing for that long, and I felt very comfortable there. And then I went in for Cleon Jones, who was sick most of the game and throwing up out in left field, and it’s 35 degrees, I think. And [A’s third baseman] Sal Bando, hits a line drive out to left center field, and somehow I reacted and went and snagged that ball. It’s just kind of a surreal, you wonder, just who’s helping you make these moves.”

His days as a major league Met ended in 1974 (he’d retire after a 1975 at their Tidewater AAA farm), but that year handed him another kind of gift: he met a Met fan from Queens named Sabrina, who eventually became his wife and a Salt Lake City elementary school teacher.

Theodore cherishes his memories with the Mets, especially having as a teammate Hall of Famer Willie Mays in his final major league season until nagging injuries and age finally wore him down for good. And he cherishes likewise that Met fans still remember and appreciate him. But like his fellow pre-1980, short-career players, the Stork wishes only that some way, somehow, baseball will redress their pension shortfall more fully.

“We’re now in our 70s and 80s and maybe 90s, some players,” he said. “Just keeping this issue in the forefront is the best thing . . . Eventually, somebody who really has the power may say hey, I didn’t realise this was happening, let’s do something about it . . . Hopefully something can happen. If nothing more, the [Weiner-Selig] annuities can be increased. It’s amazing that we got the annuity in many ways.”

It would be more amazing if baseball awakened wide enough to understand Theodore and his fellow pre-1980, short-career players were frozen out of proper pensions wrongly in that 1980 re-alignment. At least as amazing as Theodore’s 1973 Mets turned out to be.