Teenage Met Ed Kranepool listens to Professor Stengel, 1962.

As a teenage prospect out of New York’s James Monroe High School, Ed Kranepool landed an $80,000 bonus plus incentives to sign with the original Mets. He spent what the government let him keep of the bonus partly on a Thunderbird convertible and mostly on a split-level home for his widowed mother in White Plains.

Then he caught his first airplane flight ever to join the Mets in Los Angeles. Lucky him. He landed in time to join the team on the June 1962 day Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax no-hit them. The seventeen-year-old missed getting into the game; manager Casey Stengel wanted a pinch hitter late but decided on his old Yankee platoon hand Gene Woodling instead.

“Thank God,” Kranepool was recorded as saying. He’d have to settle for playing on the losing side of three no-hitters including Hall of Famer Jim Bunning’s Father’s Day 1964 perfect game.

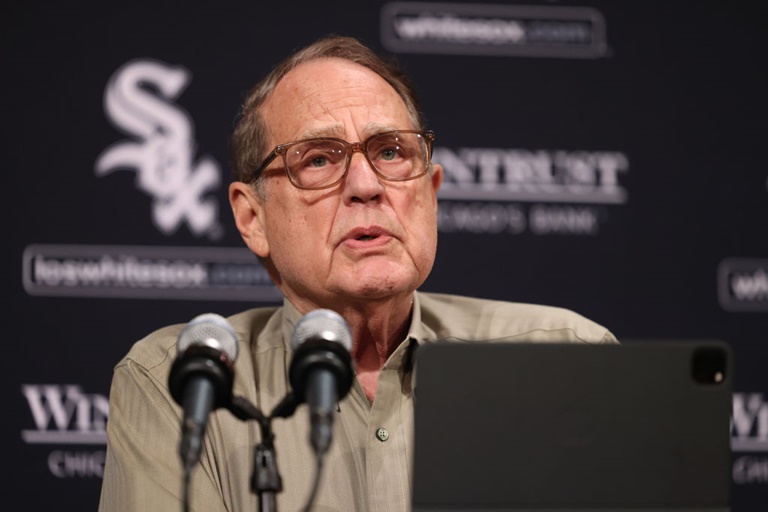

A kid who begins his major league life as a 1962 Met surely had something to say about this year’s Blight Sox who threaten those Mets’ record for season-long futility. “I’ve gotten calls lately about the White Sox, but there’s not much to say,” said Kranepool, who died at 79 Sunday.

I don’t care if they lose more games than that original Mets team. It was a bad baseball team with a bad mix of young guys and some great older stars whose best years were behind them. In a clubhouse like that, when you’re young like I was, all you want is to learn and get better and have the season end. But whether the White Sox finish with more losses than that team—what does it matter to me?

Kranepool didn’t just have that season end. Before the decade ended, he’d go as he once phrased it, “from the outhouse to the penthouse,” as a member of the 1969 Miracle Mets. The outhouse years were rarely pretty for a kid upon whom wild expectations were piled. On the other hand, Kranepool developed a Metsian sense of humour about it.

He was one of only two licensed stock brokers playing in the National League at the time; Bunning was the other. He took to discussing Mets life in stock market terminology.

“During the World Series,” he told New York Times sportswriter Joseph Durso in 1967, “the Dow-Jones wire carries the score every inning, plus the home runs and pitchers. Wouldn’t it be great if the Mets got into the Series and I hit a home run that was flashed over the ticker along with the quotations? Boy, the office would go wild.”

A few million offices and residences in New York, when it actually did happen to both the Mets and Kranepool two years later. The Mets shook off a Game One loss to demolish the Orioles in four straight . . . and Kranepool smashed a one-out homer off Oriole reliever Dave Leonhard, sending a slightly hanging breaking ball over the center field fence with one out in the bottom of the Game Three eighth.

He had an up and down relationship with his teammate-turned-manager Gil Hodges, though. Both men headstrong but one the boss who’d survived World War II and the other a young man whose father was killed in that wae before he was born. They butted heads often as not until 1971, when Kranepool had a fine if not spectacular season.

“[T]hings seemed to get a little better between us, Gil and me,” he told Maury Allen for After the Miracle: The Amazin’ Mets Twenty Years Later.

I think we were beginning to understand each other. I had matured and was becoming a more productive player. Then he got his fatal heart attack in West Palm Beach that next spring of 1972, and Yogi [Berra] took over. Maybe I never appreciated Gil. I don’t know. He was a hard man to get to know. He was very tough, very strong. But he was smart. I think he was the first to know in 1969 how good we were.

Just like any other manager asked after a miracle Series triumph to explain how it came to be and answering by spreading his palms apart, grinning, and saying, “Can’t be done.” Kranepool thought otherwise. “Gil was a great manager, a very smart baseball man,” he told Allen. “I’m sure I would have learned a lot more about the game if he had lived.”

When Wayne Coffey wrote They Said It Couldn’t Be Done a few years ago, for the 50th anniversary of the 1969 Mets, Kranepool was even more concilatory, even if it could only be with Hodges’s ghost. “We really were a team,” he began.

Sometimes you win in spite of your manager, but not with this club. Gil did everything right. He made every possible move to help our club. He never tricked you. He was so consistent . . . You never showed up at the ballpark not ready. Once he said he was going to do something, he stuck to it. You were prepared when you went to the park. You got your rest. You were ready. You worked hard to stay in shape because you knew you would be called on. He kept everybody sharp.

Kranepool never became a bona fide superstar, but he remained iconic in New York, especially when he enjoyed a late career second life as a successful pinch hitter. Three years ago, studying pinch hitters with over 300 plate appearances since the heyday of their patron saint Smoky Burgess, I ranked Kranepool number sixteen according to my Real Batting Average metric. (TB + BB + IBB + SF + HBP / PA. Kranepool: .484 RBA.) Shea Stadium rocked with “Ed-die! Ed-die!” chants every time he loomed as a pinch hitter.

As content as he became with his Mets career as it was, as embittered as he became over the team’s mal-administration following the death of their beloved original owner Joan Payson (“Joan Payson was like a grandmother to me and to everybody else,” he once said), Kranepool came to take a realistic view of his Mets life. (His eighteen-season tenure remains a Mets record.) Including the ill effect of rushing a seventeen-year-old to the Show and not exactly letting him develop in short minor league stints in the seasons to follow.

“They shoulda left me in the minor leagues to develop, and they woulda got a better player out of it,” Kranepool was once quoted as saying. “A kid of seventeen isn’t equipped to handle that pressure. They said, ‘Ed’s going to lead them from a bad ballclub to the pennant.’ One player, even a Hall of Famer, can’t do that.”

Ed Kranepool (at the podium) addresses a Citi Field crowd on the 50th anniversary of the 1969 Mets. Listening, left to right: Jerry Grote (C), Jerry Koosman (LHP), Cleon Jones (LF), Ron Swoboda (RF), Duffy Dyer (C). (Bergen Record photo.)

Nobody questioned his fortitude. After one such brief minor league turn in 1964, Kranepool was recalled to the Mets in time to play a doubleheader . . . all 32 innings of it at first base. He went 4-for-14 on the day/night with two runs scored, plus a double and a triple among the four hits. His mother went the distance with him in the Shea Stadium stands . . . because she was holding onto his car keys and house keys.

After his playing career ended. Kranepool took up life as a businessman, made peace with future Mets administrations, and became a happy presence at assorted Mets functions and commemorations as well as spring training. He also dealt with diabetes and kidney disease, receiving a transplant in 2019 after a two-year wait that was frequent news in New York. (A then-59 year old Met fan–whose own husband had received such a transplant—turned up as the donor.)

“I knew Krane for 56 years,” said Miracle Mets outfielder/first baseman Art Shamsky. “We did so many appearances together. We had lunch last week and I told him I would be there next week to see him again. I’m really at a loss for words. I can’t believe he’s the fourth guy from our 1969 team to pass this year.”

“We knew each other so well,” said pitcher Jerry Koosman, “and I could tell by his eyes if a runner was going or not. He saved me a lot of stolen bases.”

Kranepool’s death of cardiac arrest followed the 2024 deaths of shortstop (and eventual Mets coach and manager) Bud Harrelson, catching anchor Jerry Grote, and pitcher Jim McAndrew. As Mets together, those plus others listened attentively whenever Kranepool told them of those early Met seasons as lovable losers.

“We used to celebrate rainouts,” the man the fabled Shea Stadium Sign Man, Karl Ehrhardt, once called the Killer Krane would say.

In time Kranepool would be respected by teammates for baseball smarts as well as his straight, no chaser personality. A personality that compelled his teammates to name him their player representative as the Major League Baseball Players Association began finding its wings after hiring Marvin Miller to run the union.

“I wasn’t afraid to protect the players and attend the meetings and the associations,” he once told a reporter. “And the players, themselves, that doesn’t bode well for you, sometimes, when you’re speaking on behalf of the group, owners can take it as a bone of contention. I wasn’t afraid of getting traded, nor was I afraid of speaking out against others’ interests.”

Kranepool and his first wife, Carole, raised a son who was athletic but far more interested in music and electronics and ultimately raised two sons and a daughter himself. Kranepool remarried happily a Sotheby’s realtor named Monica whom he met during his stock brokering days. (She has four grandchildren of her own.)

“I’ve been lucky to have a great team at home—my wife and family. And also the Met organization,” he said after his transplant. “I’ve been with them since 1962. Those are the only two teams I knew up until that time. Now I have an extended team.”

He didn’t just mean his medical team, either. Kranepool was also one of several Mets who set up Zoom calls with residents of assorted elder care facilities, during the original COVID-19 pan-damn-ic, as a way to pay forward his kidney transplant. “This is a summer that none of us will forget,” he told northjersey.com writer Justin Toscano. “You’re always looking to talk to somebody to brighten their day, and hopefully they can brighten mine.”

He needn’t have worried. He had an immediate and extended family to brighten his days. He now has an even more extended one welcoming home to the Elysian Fields. Led, perhaps, by the skipper whom he didn’t always understand but who probably greeted him with, “We’re ok, Eddie. You got the point, after all.”