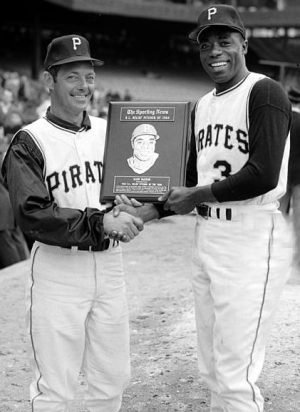

Stepping up when relief ace Elroy Face (left) struggled in 1964 earned Al McBean (right) the Sporting News Fireman of the Year (NL) Award he displays proudly with Face here.

Al McBean was both major league baseball’s first Virgin Islander by birth and a first class character. The righthander with the hard sinkerball who died at 85 at home Wednesday seems never to have met a situation he couldn’t clown his way through. Even opponents didn’t seem to mind.

He was “the funniest man I have ever seen in a baseball uniform,” Hall of Fame second baseman and manager Red Schoendienst once said of him.

Even the way McBean came into a game from the bullpen got laughs. “Whatever those walks mirrored,” wrote the Philadelphia Daily News‘s Sran Hochman in 1963, “concentration, determination, or intoxication, nobody walked into a game the way Alvin O’Neal McBean walks into a game.”

Writing McBean’s full name may have been drawn from longtime Pirates broadcast Bob Prince, who seemed to love referring to McBean that way. But about those walks in from the pen, McBean’s manager Danny Murtaugh said, “You’d have to say McBean saunters in.”

He never apologised for enjoying life and the game. “My thing was fun,” McBean told Society for American Baseball Research biographer Rory Costello in a 1999 interview.

I liked to do little crazy things, something different for the fans, they see the same thing over and over and over. Like crawling over the foul line and not touching it. Throwing the first pitch underhand, pulling on a big red bandana and wiping my face with it. Something the fan can feel a part of.

But the guy who went to a Pirates scout’s tryout in 1957 as a press photographer (he was goaded into trying out and ended up signing with the Pirates for a $100 bonus) also liked to learn as much about the game as he could. One of his teachers was Elroy Face, the Pirates’s star relief veteran.

“I used to go to his house, barbecue a lot, pal around with his family,” McBean told Costello. “And he would tell me intricacies of the game. You could get a guy on, walk a few guys once in a while, based on how you felt that particular day. Learn how to pitch in those situations.”

Though inconsistency dogged him much of his career, McBean actually got to step in for the main man when Face struggled in 1964. McBean had posted a brilliant 1963 (2.57 ERA, 2.81 fielding-independent pitching rate, over 122.1 relief innings pitched in 58 games), then went out and all but equaled it in ’64. (1.91 ERA, 2.97 FIP, 1.04 WHIP, 89.2 innings in 58 games.)

That earned him the Sporting News‘s 1964 National League Fireman of the Year award, placing McBean in some very distinguished company: the American League winner was Red Sox legend Dick (The Monster) Radatz. And Face himself won the NL award two years earlier.

Not that McBean’s prize win was simple. Four attempts to send McBean a commemorative trophy to his Virgin Islands home resulted in broken goods in shipment. When an unbroken trophy finally arrived, McBean “erupted in mock outrage,” Costello recorded—he’d wanted the head to have a fireman’s hat atop it.

That was the least of his problems. He went to Puerto Rico to play winter ball after the ’64 season and became the subject of rumoured death threats. Heavy bettors among fans were said to have suffered heavy losses in McBean’s games and were reported to be considering shooting the effervescent righthander.

McBean continued his stellar relief work in 1965 while Face missed much of the season with a knee injury. Then Face returned healthy for 1966 and McBean lost plenty of chances to nail down Pirate wins. He had three more decent seasons for the Pirates before they exposed him to the second National League expansion draft and the newborn Padres took him.

Oops. The Padres weren’t prepared for McBean’s freewheeling kind of fun. Costello records that he asked where to find the nearest spa—and worked out in a dance leotard. McBean ended up getting one start for those 1969 Padres . . . and traded almost promptly to the Dodgers for a pair of no-names. It was the only trade between those two teams for almost three decades.

But he got a return engagement with the Pirates when the Dodgers released him a year later and the Pirates picked him up. After looking nothing like the way he once was at age 32, McBean got what proved his final release. He played winter ball in Puerto Rico again in 1970-71 before the Phillies signed him and sent him to their Eugene, Oregon (AAA) affiliate with an apparent promise to bring him up if he did well.

He did well enough at Eugene, but the Phillies opted instead to bring up a far younger pitcher named Wayne Twitchell, about whom the most memorable thing (other than a nasty knee injury that compromised his career) was getting an All-Star appearance and a public compliment from Hall of Famer Steve Carlton before Carlton went completely silent to the press.

When the Phillies demoted him to AA-level ball for 1972, McBean retired and went home to the Virgin Islands permanently. He once claimed his sole regret was making the Pirates after one World Series championship and leaving them before another: “I have never seen myself pitch,” alluding to the broadcast highlights now ubiquitous on YouTube.

He joined St. Thomas’s department of housing, parks, and recreation, and co-founded the city’s Little League program, before becoming the housing, parks, and recreation department’s deputy commissioner. He never lost his zest for life or love for baseball even if he became critical of changes in the game in the years that followed his career.

He bemoaned guaranteed big contracts compromising players’ hunger for the game; he zinged the vaunted Braves starting rotation of the 1990s for their corner life (only Hall of Famer John Smoltz escaped his snark: “At least he comes after you”); he dismissed Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn as “a [fornicating] banjo hitter”; he swore Hall of Famer Frank Thomas would be putty in his sinkerballing hands. (“The Big Hurt, my ass. I would eat him up.”)

Well, nobody’s perfect. (Though it’s not unreasonable to think that maybe, just maybe, McBean might well have done well against the Big Hurt: Thomas’s lifetime slash line hitting ground balls that good sinkerballers normally get—.268/.268/.293/.561 OPS.)

The guy whose best man at his 1962 wedding to Olga Santos was Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente (McBean once posited that Clemente was a better all-around player than his fellow Hall of Famers Henry Aaron and Willie Mays) didn’t have to be perfect. He just had to be himself.

What I enjoyed most from baseball was the camaraderie that I had with the fans in Pittsburgh. The signing of autographs, then going to people’s homes for dinner. Mt. Lebanon was one of my areas, real nice–I used to wear the little black thing on my head, I didn’t know what it was for, but I wore it anyway! Up at St. Brigid’s Parish, I knew most of the nuns there, they’d come to Forbes Field, they’d come down to the bullpen and we’d talk. I’d go to church up in the Hill District. I would drink dago red. I had fun basically with everybody.

That was the man who is said to have had a run-in with segregated facilities during one spring training by drinking water from a fountain marked “white only” and crowing, “I just took a drink of that white water and it’s no damned different from ours!”

The man who pursued his future wife by showing up at the Puerto Rican drugstore where she worked while he played winter ball, buying soap from her daily until she agreed to go on a date with him. His love affair with Olga endured on earth far longer than his pitching career.

If you thought McBean left some side-splitting memories around baseball, you can only imagine what his Olga, his daughter Sarina, and his three grandsons have to hold until they meet again in the Elysian Fields.