Strange circumstances or no, Fred McGriff is now a Hall of Famer.

I have absolutely no complaint about Fred McGriff’s election to the Hall of Fame. I’d been on the fence about him for a long enough time, and said so in other places, but I knew one thing above all: the Crime Dog had a borderline Hall case, isn’t the worst first baseman or the worst player overall to get a Cooperstown plaque, and would be an honourable selection in his own right if he made it.

He made it Sunday, courtesy of the Contemporary Baseball Era Committee.

If you use my Real Batting Average metric (total bases + walks + intentional walks + sacrifice flies + hit by pitches, divided by total plate appearances), McGriff’s .594 falls smack dab in the middle of the pack of Hall of Fame first basemen who played in the post-World War II/post-integration/night-ball era. It also gives him a 28 point edge over the last first baseman elected to the hall by an Era Committee:

| First Base | PA | TB | BB | IBB | SF | HBP | RBA |

| Fred McGriff | 10174 | 4458 | 1305 | 171 | 71 | 39 | .594 |

| Gil Hodges | 8104 | 3422 | 943 | 109 | 90* | 25 | .566 |

Actually, I knew one other thing above all about McGriff. If he wasn’t part of the absolute worst trade in Yankee history, he was at least part of the worst trade they made in the 1980s. They traded McGriff (then a minor leaguer) plus infielder Dave Collins, relief pitcher Mike Morgan, and cash, to the Blue Jays, for infielder Tom Dodd and relief pitcher Dale Murray. The best days of a modest career were behind Collins; Morgan was on the way to a respectable 22-season career as a hard-luck starter turned valued reliever.

For McGriff, it was a case of hiding in plain sight. Steinbrenner made Tampa his home; McGriff hailed from Tampa. Yet Steinbrenner was absolutely unaware McGriff even existed. The Boss and the rest of the American League would learn soon enough. Once he became a Toronto regular, the Crime Dog bit the league for an average 35 homers per 162 games in Blue Jays silks—including the league’s home run championship in 1989.

Fair play requires us to acknowledge that, even if Steinbrenner was aware of McGriff, the Crime Dog-to-be (fabled nicknaming broadcaster Chris Berman hung that on him in due course) was blocked at first base by some guy named Mattingly. And it took McGriff a few more years to be fully major league ready, which would have been fine except that patience was never a Steinbrenner virtue.

Like his Hall of Famer contemporary Mike Schmidt, McGriff didn’t just hit home runs, he hit conversation pieces. He didn’t exactly look the part; he was movie-star handsome and not musclebound, though his Blue Jays teammate Lloyd Moseby once said, “I wish I could get Freddie to lift weights. The only things he lifts are candy bars.” But he didn’t look like a man who needed multiple Milky Way fixes, either.

McGriff’s problem was that he became one of the game’s premier power hitters in an era when a lot of others actually or allegedly used actual or alleged performance-enhancing substances. (Burning question still: if Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire, and Sammy Sosa—plus pitching great Roger Clemens—must remain persona non grata in Cooperstown, how do you justify electing their chief enabler, then-commissioner Bud Selig?)

If he’d played with the same skill set and statistics in a career beginning a decade sooner than it did, he’d have been a Hall slam dunk—regardless of not quite reaching the 500 home run plateau. In the age of the Bondses, McGwires, and Sosas, the Crime Dog didn’t look that ferocious. But even without that age’s taint, he didn’t look like the guy who did what he did, a guy who could hit a wet T-shirt and send it into the seats.

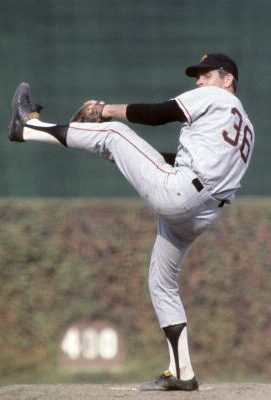

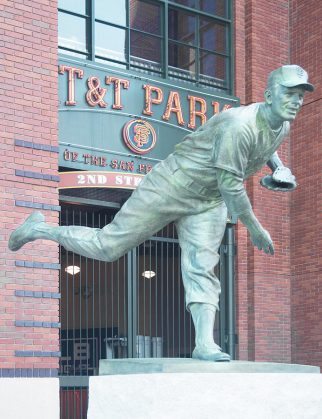

He merely had the second-most elegant home run swing I ever saw. (Darryl Strawberry’s was numero uno.) He really did look as I saw him described once, a man who looked as though conducting a symphony orchestra (as he was about to ring down the final crashes of The 1812 Overture) after he swung and a smooth neon dance figure during his swing.

The looks weren’t everything, of course. Had it not been for the 1994 owners-provoked players’ strike, McGriff probably would have finished his career with somewhere around 503 home runs. (He averaged 32 per 162 games lifetime and had 37 when the ’94 strike launched. It’s not unrealistic to think he might have had at least ten more in him.)

McGriff’s second problem was that, if he was an executioner at the plate, he was a sieve at first base. He finished his career -32 defensive runs below his league average. Like Gary Sheffield in the outfield, McGriff at first base torpedoed his own value with his defense. His 52.6 wins above replacement-level player (WAR) should have been better but his -17.2 defensive WAR put paid to that.

He also had a third problem, enunciated best by Cooperstown Cred writer Chris Bodig: “McGriff had an aw-shucks level of humility throughout his playing days. Because he played for six different teams, the Crime Dog never had a passionate following of one city’s fan base, which might have contributed to his lackluster results in the Hall of Fame voting.”

I suspect these factors played larger into McGriff finally being elected to the Hall than a lot of his partisans (he has more than you might think) might care to admit:

1) The election of Harold Baines by the 2019 Today’s Game Committee. Baines had no Hall case other than his career length. (He didn’t even have a single signature moment to hoist him above his contemporaries.) But he did have . . .

2) A Today’s Game Committee packed with men who played with, managed, or oversaw Baines on a few teams: Jerry Reinsdorf, who became the White Sox’s owner when Baines was first settling in with the team and re-acquired Baines twice more to come; Tony La Russa, the Hall of Fame manager who managed Baines with the White Sox and the Athletics; and, Pat Gillick, who was the Orioles’ general manager when Baines played there.

3) McGriff had the same benefit on this year’s Contemporary Baseball Era Committee: three Hall of Fame Braves teammates (Tom Glavine, Chipper Jones, Greg Maddux, though Jones took ill and couldn’t be part of the vote); a Blue Jays executive (Paul Beeston) during McGriff’s years there; a brief Blue Jays teammate turned executive (Ken Williams).

That’s dangerously close to the kind of cronyism that sent the ancient Veterans Committee into disrepute over the years Hall of Famers Frankie Frisch and Bill Terry oversaw the committee, hell bent on getting as many of their old cronies from the Giants and the Cardinals into Cooperstown as they could get away with, regardless of their actual Hall credentials.

“Baines’ election is simply not a great day for the institution, or for anyone bringing an analytical, merit-based approach to it while reckoning with its objective standards,” wrote The Cooperstown Casebook author Jay Jaffe upon Baines’s election. “The precedent it sets is nearly unmanageable, if future committees are to take seriously candidates of his level. Why battle over Dale Murphy or Fred McGriff if Harold Baines is the standard?”

McGriff had fifty times the Hall case Baines lacked. Murphy’s Hall case was torpedoed by knee injuries that shifted what should have been a natural decline phase into sad overdrive. Don Mattingly’s was torpedoed by his back. If all you needed was character, those two would have been Hall locks otherwise, long before they arrived and departed on this Contemporary Baseball Era Committee ballot.

But another entrant on that ballot, Curt Schilling, torpedoed himself. He got seven out of the needed twelve committee votes despite being a no-questions-asked Hall of Fame-level pitcher. His ability to miss bats (he has the highest strikeout-to-walk ratio in the game’s history), his dominance when the heat was truly on, and his postseason resume live up to his well-known thirst for wanting the ball in the highest heat. He was the very essence of a big-game pitcher, and he has three World Series rings to show for it.

But a guy who applauded lynching journalists and became too much of a disinformation retriever wasn’t exactly going to keep friends among the voting writers. A guy who fumed publicly when several such voters sought to rescind their votes for him was pretty much asking, as he did in a letter to the Hall, for just what he didn’t get from the Contemporary Committee, enough of whom couldn’t suffer that kind of fool gladly:

I will not participate in the final year of voting. I am requesting to be removed from the ballot. I’ll defer to the veterans committee and men whose opinions actually matter and who are in a position to actually judge a player.

Whoops.

But if the Committee had to elect only one man, it doesn’t sully the Hall further by electing McGriff. He was a genuinely great hitter. If I was on the fence about him on the borderline as long as I was, it won’t deny me pleasure in seeing him at the Cooperstown podium in due course. Maybe he’ll even wolf a candy bar down before he speaks.