Little did Tom Verducci know that when he pegged Matt Harvey as the Dark Knight that another kind of darkness would compromise Harvey’s once-promising career.

Ten 7 Junes ago, the Kansas City Royals with the number four pick elected to draft a Cal State-Fullerton shortstop named Christian Colon instead of a University of North Carolina pitcher named Matt Harvey—because they thought they had enough pitching.* The New York Mets in the same draft picked two pitchers: Harvey, with the number eight pick overall, and a Stetson University kid named Jacob deGrom.

Five years after that draft, Harvey bulldozed his manager Terry Collins into letting him try to finish a World Series Game Five shutout that would have sent the set to a sixth game back in Kansas City.

“Would I take back getting to the World Series with those guys and the city of New York?” Harvey asks now, before answering. “There’s not a chance. I believe things happen the way they are supposed to. I got hurt and maybe I would have anyway. Getting to the World Series was worth it.”

Then Collins had to lift his gassed Dark Knight after a leadoff walk and an RBI double and bring in his closer Jeurys Familia, who already had a sick-looking Series resume thanks to those Mets’ porous infield gloves. Unfortunately, you can’t give the blown save to the defense under the save rule.

Two groundouts, then a terrible throw home to complete what should have been a simple game-ending double play, and Game Five went to extra innings. Where Colon, pinch hitting for Royals reliever Luke Hochebar, broke the two-all tie in the top of the twelfth, opening a five-run inning that won the Series for the Royals after the Mets couldn’t get a single baserunner past second in the bottom of the frame.

Today, deGrom—who waited until the ninth round before the Mets took him, too, ten years ago—is the National League’s back-to-back defending Cy Young Award winner. Arguably, he’s also the best pitcher in the game right this moment, among those not named Max Scherzer or Gerrit Cole.

Harvey, whom the Mets traded to the Cincinnati Reds in 2018, who signed as a free agent with the Los Angeles Angels for 2019, who was released after that experiment tanked, and who gave it another try in the Oakland Athletics system the rest of the season, now looks for a job. In the Korean Baseball Organisation.

MLB’s tug-of-war between the owners and the players over the financials in getting a coronavirus-delayed 2020 season in at all probably meant it was a very long shot for Harvey to catch on with another major league organisation for now. He doesn’t mind taking his chances otherwise.

“It’s been an interesting ride, a roller coaster,” Harvey tells the New York Post. “With where I am now, physically and how I’m feeling, I hope I get another shot.” Calling it “an interesting ride” may be an understatement. Which is saying something about a pitcher you could call many things other than understated.

“As soon as he signed, he came to New York. I saw this big, good-looking kid standing in our bullpen with a black suit, white shirt, very thin tie — very GQ-ish, as he always was,” the Mets’ then-pitching coach Dan Warthen tells the Post. “His hair was always perfect. Then you see the ball coming out of his hand and you say, ‘Oh, it won’t be long until he’s playing baseball up here.’ And he was cocky, oh Lord. He said, ‘Hey, I’ll be ready to pitch for you next year’.”

Harvey premiered for the Mets in late July 2012, against the Arizona Diamondbacks. He struck out ten in five and two-thirds innings while walking three and scattering three hits. “All of the reports I read,” says then-Mets manager Terry Collins, “didn’t talk about a 98 mph fastball. It was ’94-95, pretty good slider, working on changeup.’ All of a sudden, this guy is throwing 97-99 with a 92-mph slider. I said, ‘Holy cow!’ We were shocked by what we saw.”

“When he burst on the scene with a fury, it was fun, man,” then-Mets pitcher Dillon Gee—whose own career was sapped by injuries until he retired last year—tells the Post. “You had heard about him coming up. When he got here, he was like on a different level. You could tell he was a special talent.”

By the following season, Harvey was practically the talk of the town in New York baseball. When he ended June 2013 with a 2.00 ERA, Met fans has already begun greeting his starts with “Happy Harvey Day!” Harvey started that year’s All-Star Game—which was played in Citi Field, his home ballpark. The American League went on to win, 3-0, but Harvey’s three strikeouts in two innings electrified the joint.

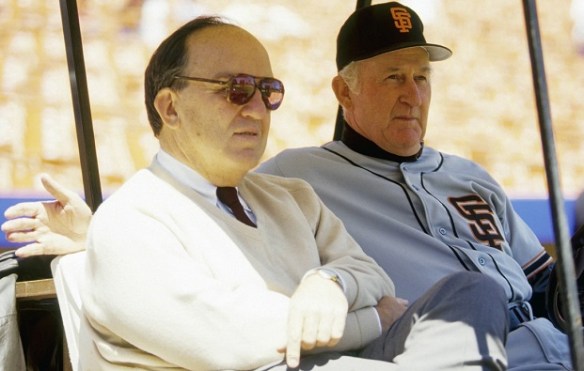

Then Sports Illustrated put Harvey on the cover with the headline, “The Dark Knight of Gotham.” But the writer who delivered that cover story, Tom Verducci, would write five years later, after Harvey pitched (and, many said, partied) his way out of New York, “The truth is, for all the times he wound up in the tabloids other than the sports section, Harvey failed because his arm failed him.”

. . . His arm likely failed him because of how he threw a baseball. And when his arm failed him, he knew no other way. He couldn’t pitch without an A-plus fastball, he couldn’t embrace using a bullpen role as a way back, and he couldn’t believe in himself again.

. . . The Mets cut Harvey because his once-fearsome fastball became the almost exact definition of a mediocre fastball (MLB averages: 92.7 mph, 2,261 rpm). Because he couldn’t find another way to get hitters out, because he could not change his mechanics and because he could not buy into the bullpen, the Mets could not keep sending [him] out to the mound as a starter.

The decline in his stuff was obvious. And there was no way his fastball was coming back with the way he throws.

Especially not after blowing his elbow ligament into Tommy John surgery late in 2013 (which didn’t keep him from leading the Show with his 2.01 fielding-independent pitching rate or third in the National League with his 2.27 ERA), or incurring thoracic outlet syndrome, the surgery for which cuts somewhat invasively into the shoulder and the back, or trying too hard to come back too soon from both.

Be very afraid, Pittsburgh Pirates fans. Your struggling pitcher Chris Archer (though he did pitch decently after last year’s All-Star break) just underwent thoracic outlet syndrome surgery himself, who probably won’t return if and when major league baseball returns, and who may even find himself receiving a contract buyout before he can pitch 2021 and hit free agency after that season.

Like Harvey, alas, Archer’s post-surgery career prospects don’t look as promising as he himself formerly looked.

“I had TOS,” Gee says. “I know how much that sucks. It definitely changes you. You start trying to tinker with things. It’s not natural anymore. You start being robot-ish. You start not trying to hurt one area and totally hurt another area. Your whole body is out of whack.”

The limelight and the taste for night life among New York’s demimonde certainly didn’t help Harvey in the long run. “You could see the media and limelight kind of became part of what he wanted to do,” says Gee. “I’m sure that is super, super hard not to let that creep in, as popular as he got. I couldn’t imagine being bombarded as he was. He was the guy.”

Who’s to say, too, that Harvey didn’t sink into the demimonde because the slow realisation that his body began betraying the talent that got him there in the first place was too painful to bear? Dark Knights are supposed to be invincible, right?

Verducci believes Harvey’s mechanics both took him to the Show and eroded him soon enough. “Harvey pulls the ball far behind him—crossing the airspace over the rubber,” he wrote, “a strenuous maneuver that rarely leads to long careers.”

Harvey’s psyche also may have fallen out of whack in 2017, when that May Brazilian supermodel Adriana Lima, with whom he thought he had an enduring romance in the making, parted with him to leave a tony Manhattan afterparty with her former boyfriend, a New England Patriots football player.

Up to that point Harvey’s taste for the charms of supermodels was rivaled only by his taste for a ride whose value sometimes equaled that of a modest suburban home. But a few days later, Harvey missed a game claiming a migraine but possibly suffering a ferocious hangover, as the Post‘s Page Six had it. It got him a three-day suspension from the Mets.

Then Harvey suffered yet another injury, a stress fracture in his shoulder area, ending his 2017 and draining more off his fastball. The following season, in which he approached his first free agency, his continuing decline prompted then-Mets manager Mickey Callaway to think about moving him to the bullpen to rehorse, a move that tasted to Harvey rather the way Brussels sprouts taste to small children.

“We were trying to get him to use his curveball and changeup more, which he did in spring training — and he had a nice, four-pitch mix,” says then-Mets pitching coach Dave Eiland. “And then once the regular season started, he went back to his old habits, fastball and slider primarily. The command of it wasn’t quite there. If he missed a little bit, the outcome was going to be a little different than when he missed 97-99 with a 92-93 slider.”

When Harvey rejected the bullpen option, sometimes nastily, the Mets designated him for assignment, then dealt him to the Reds.

“I gave him the Dark Knight nickname, because I saw in Harvey someone who not only had the stuff to save the Mets in Gotham—they were in the middle of six straight losing seasons when Harvey arrived—but also the desire to play the role,” Verducci wrote. “He embraced not just being a staff ace but also a dominating personality.”

Learning to be just a young man may be almost as tough as re-learning how to pitch. Once upon a time Harvey was the most identifiable Met to the public but a somewhat alienating one inside his own team. Maybe riding the high life too hard distanced Harvey from people who might otherwise have felt for him, empathised, wanting to feel for him.

In Cincinnati and in Anaheim he was described as a changed young man, not exactly the type to just jump when the siren call of a tony party beckoned. If Gee and former Mets general manager Sandy Alderson are any examples, there’s empathy now, even if through hindsight’s eye.

“I liked Matt. I continue to like Matt,” Alderson tells the Post. “Sure, he had his reputation, but ultimately I thought as an individual, he was sort of a vulnerable person. Someone whose confidence was a little brittle. I remember in his postgame interviews, he came across as a real solid, humble, genuine guy. The things that we went through with him were not novel for me. It was part of the job. I didn’t resent it at all. I didn’t take it personally.”

Alderson isn’t the only one with a hindsight’s eye view of the Harvey dilemna. The former Dark Knight has one of his own. “There are a lot of things I’d do differently,” the 31-year-old Harvey now says, “but I don’t like to live with regret.”

There were just things I didn’t know at the time. Now, obviously, I’ve struggled the last few years. And what I know now is how much time and effort it takes to stay at the top of your game. I wouldn’t say my work ethic was bad whatsoever, but when you’re young, it’s not like you feel invincible, but when everything is going so well, you don’t know what it takes to stay on the field. It’s definitely more time consuming and takes more concentration.

Pitching respectably in Cincinnati got Harvey that shot in Anaheim that collapsed last year. The word now is that the video he’s produced of a pitching workout may impress someone in the KBO to give him a try. Eiland says he’s seen the video and it shows Harvey’s arm “looked like it was working well.” Warthen agrees: “This is the cleanest and easiest that I’ve seen him throw the baseball in a long time.”

Harvey also looks healthy. Shorn of his once-familiar beard, he looks as young as he was when the Royals bypassed him and the Mets snapped him up ten years ago. Almost as though he’d erased all those nights on the town and the flash he once embraced, except from inside his mind and soul where he can review them and remind himself how not to do it.

If Harvey can suggest that he knows better now what it takes to stay on the field or the mound, it’s an even more encouraging sign. It could also mean him trying to fend off the possibly inevitable one last time. It could also mean Harvey having to come to terms at last with the possibility that whatever else fell out of whack in his life before, his body’s betrayal was just too profound in the long run.

——

* Colon, the shortstop the Royals preferred to more pitching in the 2010 draft, remains the reserve-level player he’s been all his major league life. Before he was waived out of Kansas City, the Miami Marlins claimed and shortly farmed him out.

The Braves signed him but released him the following May, the Mets (of all people) signed him on a minor league deal but let him walk as a free agent, then the Cincinnati Reds signed him to a minor league deal, gave him a cup of coffee last September, and re-signed him on a minor league deal.

But he’ll always have Game Five of the 2015 World Series. With one swing in the top of the twelfth he drilled his way into permanent baseball lore. It’s more than a lot of journeymen get.

In the same 2010 draft, the Royals passed over another pair of stars-to-be: outfielder Bryce Harper and pitcher Chris Sale. Harper is now in the second year of a $330 million/thirteen-year contract. Sale was the last man standing—striking out the side in the Game Five ninth—when the Boston Red Sox won a 2018 World Series that may or may not be tainted by their replay-room sign-stealing cheating that season.