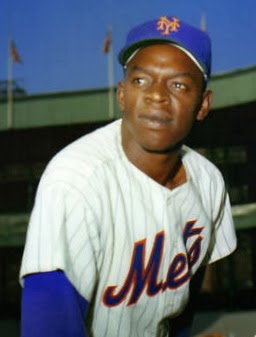

Al Jackson pitching to Hall of Famer Willie Mays in Shea Stadium, 1964. Jackson was a control pitcher whose Original Mets were only too often beyond control.

With the National League’s teams agreeing to let the expansion Mets and Colt .45s (the Astros-to-be) pick only from among their flotsam and jetsam, the two new clubs didn’t have much in the way of quality choices. As the Colts’ first general manager, Paul Richards, said infamously to his crew, “Gentlemen, we’ve just been [fornicated].”

The Colts went for younger unknowns, predominantly, though they did pick a few veterans, notably pitchers Don McMahon and Bobby Shantz, infielders Joey Amalfitano and Billy Goodman, and first baseman Norm Larker.

Knowing New York still smarted over the Dodgers and Giants moving west, the Mets opted mostly but not exclusively for veterans with National League name recognition (several of whom were former Dodgers or Giants), suspecting that might help goose the box office while the Mets set about building an organisation that might bear fruit within the decade.

Their choices included Hall of Fame center fielder Richie Ashburn, first basemen Gus Bell, Ed Bouchee (the NL Rookie of the Year runner-up in 1957), and Gil Hodges (the Brooklyn favourite), infielders Felix Mantilla and Don Zimmer, outfielder/first baseman Frank (The Big Donkey) Thomas, catchers Hobie Landrith and Joe Pignatano, and pitchers Roger Craig and Clem Labine.

But they did make room, too, for younger players who were either spare parts on other clubs or lucky to get cups of coffee if that much. Maybe the best of the Mets’ finds out of the latter end of the pool was a lefthanded, African-American pitcher named Al Jackson, whom the Mets plucked from the Pirates. To whom manager Casey Stengel took an immediate liking.

“Jackson,” wrote Stengel’s biographer Robert W. Creamer, “was one of the few accomplished players that Casey had when he was managing the Mets, a fine pitcher who could field his position skillfully, handle a bat well, run bases intelligently, and pitch with guile and courage.” The feeling was mutual. “He never treated me with anything but respect,” Jackson once said.

The Waco, Texas native died Monday morning at 83 in a Port St. Lucie, Florida nursing home, following a long illness that came in the wake of a 2015 stroke. Met fans from my generation won’t forget the game he pitched to open 1964’s final regular season weekend. In which, for the very first time in their existence, the Mets actually mattered to a pennant race outcome.

In fact, the infamous Phillie Phlop threatened the prospect of a three-way tie for the 1964 National League pennant. Thanks to that ten-game losing streak eroding what was a six-game lead when it began, the Cardinals opened the weekend in first place by half a game, the Reds were right behind them, and the Phillies were two and a half back.

The Cardinals hosted the Mets three games in St. Louis for that final weekend. The Reds faced the Phillies for a pair. And after the Phillies won their Friday game thanks to a four-run eighth and tidy bullpen work, a Cardinals win later in the day would clinch at least a tie for the pennant. Naturally enough, the Cardinals sent future Hall of Famer Bob Gibson to the mound to dispatch the Mets.

Stengel countered with Jackson. “Jackson,” the manager liked to say, “is a pret-ty good-looking pitcher,” which Creamer wrote was high praise from the Ol’ Perfesser. And at a time when it looked like the novelty of the Mets’ comedy of errors began wearing off, and the losing quit being funny, accompanied by some increased mutterings that Stengel was losing whatever he had left, Jackson proved one of Stengel’s few defenders.

A manager who loved to teach baseball above almost anything else, Stengel savoured Jackson as one of his very few younger Mets who was willing to listen and learn—even while he was at work on the mound. “Casey would stand in the dugout,” Jackson would remember, “and say real loud, ‘If I was a lefthanded pitcher, here’s what I would do right now.’ That’s when I knew he was talking to me.”

There were men on first and second, and you knew the other team wanted to bunt them over. Casey would say, “Here’s what I would do. I would let him bunt. I would throw him a little slider, and I would break toward the third base side, and I would throw his ass out at third.” Casey had the guts to tell you what he’d do in a certain situation when it came up on the ball field. He didn’t wait until after it was over and second guess. He’d tell you right now, and he’d tell you what the other team should do. He’s the only man I ever saw do that.

Gibson and Jackson squared off. The only run of the game scored when Mets first baseman Ed Kranepool singled home outfielder George Altman with two out in the third inning. Despite Gibson striking out seven while scattering eight hits and no walks in eight innings’ work, the script got flipped—the Cardinals committed three errors to the Mets’ none, though none of the errors factored in the score.

Jackson went the distance scattering five hits and a walk and, after surviving a bases-loaded threat in the eighth, retired the Cardinals in order on two fly outs and a ground out to finish. The next day, with the Phillies and the Reds off, the Mets blew the Cardinals out, 15-7. These were the Mets? Now the National League race went from chaos to bedlam.

The blowout left the Cardinals and the Reds tied for first with the Phillies a full game back. If the Phillies beat the Reds on the final Sunday and the Mets could finish sweeping the Cardinals, the National League would have to figure out a round-robin to decide a pennant winner. The Phillies did their job, blowing the Reds out 10-0 behind Hall of Famer Jim Bunning.

Al Jackson, in the Polo Grounds, where the Mets played their first two bizarro seasons.

The Mets, alas, didn’t do theirs. Not for lack of trying. They had a 3-2 lead in the middle of the fifth, but the Cardinals dropped a three-spot on them in the bottom of the inning and never looked back; in a game that included Gibson working four innings’ relief, the Cardinals won the game (11-5) and the pennant. At the last possible minute.

Yet somehow the Mets made the Cardinals earn it the hard way, starting with Jackson’s cool shutout. A 5’10” lefthander whose money pitches were a snappy curve ball and a shivering slider, Jackson was as athletic as the day was long and pitched stoutly despite being charged with heavy losses as a Met, and his teammates befriended and respected him.

Kranepool in particular befriended Jackson, the two socialising often, even playing basketball together in the off seasons to stay in shape, according to Newsday.

“You had to be a pretty good pitcher to lose that many games,’’ Kranepool said of Jackson, who was charged with twenty losses in each of 1962 and 1965 and pitched too often in hard luck . “He was in the games at the end because he did so many things well. He was a good fielder and good hitter. He didn’t throw that hard; his curveball was his best pitch. But he was such a nice guy. He really was. You can’t find a negative thing to say about Al Jackson.’’

His fellow Original Mets pitcher, Jay Hook, credited with the win in the Mets’ first-ever regular season victory, had the same admiration. “He had good control, No. 1,” Hook says. “I think he really knew how to pitch.”

Jackson was dealt to the Cardinals after the 1965 season for veteran third baseman Ken Boyer, who was coming to the end of a should-have-been Hall of Fame career. After two fine if unspectacular Cardinal seasons, including not pitching in the 1967 World Series, he was returned to the Mets to finish a trade for relief pitcher Jack Lamabe.

He worked effectively as a swingman in his second Met tour, but before he could be a full part of the 1969 miracle—he if any Original Met had earned the chance after having survived the worst of their earliest seasons of comic futility—the Reds bought him that June. By then a middle reliever, a role that didn’t necessarily suit him, Jackson didn’t pitch as well as previously, and when the Reds released him in 1970 he retired.

He became a pitching coach for about two decades, including with the Red Sox and the Orioles, then returned to the Mets to work as a minor league pitching instructor except for a brief spell on the parent club during Bobby Valentine’s managerial term.

Jackson was as well known for good humour as he was for his pitching ability and knowledge. He needed every ounce of that good humour he could muster, as Jimmy Breslin related unforgettably in Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game. Specifically, about the third inning in a 10 August 1962 game in Cincinnati’s Crosley Field.

This one left even the even-keeled Jackson—who’d pitch the longest game in major league history in terms of the game’s time (four hours and thirty-five minutes, pitching fifteen innings against the Phillies four days later)—wondering if he’d lost his marble. Singular.

The Mets were in a 3-0 hole when Jackson surrendered a leadoff double to Hall of Famer Frank Robinson. Wally Post grounded out right back to Jackson off the mound but Don Pavletich walked to set up first and second. After Robinson stole third, Jackson got Hank Foiles to whack into a sure double play starting at first base.

Marvelous Marv Throneberry fielded it cleanly. He had all the time on earth to start the play. He could go to second for the first out and take the relay; or, he could throw home for the first out and get the relay back. “Don’t think,” Crash Davis warned. “It’ll only hurt the ball club.” Throneberry thought. Then he decided to go home to start the double play. Except that his throw didn’t arrive quite at the moment Robinson did.

Then a walk to Vada Pinson loaded the pads for Don Blasingame. And Blasingame obeyed Jackson’s pitch, too, whacking a perfect double play grounder, this time to second base. Where Hot Rod Kanehl was so anxious to pick it up and get it started that he let the ball bounce right off his leg.

“Jackson,” Breslin wrote, “now has forced the Reds to hit into two certain double plays. For his efforts, he has two runs against him on the scoreboard, still only one man out, and a wonderful little touch of Southern vernacular dripping from his lips.”

Then with Reds starting pitcher Jim Maloney at the plate, Jackson wrestled him to 3-2 and, as he threw Maloney a sure ground ball pitch, the runners broke. And Maloney whacked the ball to Kanehl. This time, the Hot Rod picked it clean. And this time, he tossed the ball to Charley Neal playing shortstop. But since the runners broke on the pitch Blasingame was already safe at second, and Pavletich scored.

Again Jackson threw what he hoped would be a double play pitch. And Cincinnati shortstop Leo Cardenas obeyed orders, whacking it on the ground right to Neal in perfect position to finish the Area Code 6-4-2 dial. “But you were not going to get Charley Neal into a sucker game like this. No sir,” Breslin wrote. Neal fired to first. Out made. Fourth run of the inning scoring.

Then Eddie Kasko lined out to Kanehl for the side. Breslin swore Jackson must have set some sort of record for getting hitters to hit into consecutive double play balls whose pooches were screwed on the first leg.

Stengel decided sending Jackson back out for the fourth would do him irreparable damage, if not what came to be known as post-traumatic stress syndrome, so he sent Ray Daviault out to work the fourth. And, perhaps flummoxed himself over the third inning’s undoings, the Ol’ Perfesser forgot to tell Jackson, who went out to the mound to warm up without seeing Daviault coming in from the pen. The Crosley Field P.A. announcer announced the Mets’ new pitcher—Daviault.

Breslin swore Jackson stopped cold and made his own announcement: “Everybody here crazy.”